Baku’s central square shares its story

The Fountain Square in Baku is considered to be the epicenter of life in the country. If a Baku resident wants to ‘see and be seen’, the square is the place to go. All the Irish pubs, brand shops, expensive coffee houses and renowned fast-food chains are located around this square and further along Nizami street.

What makes the square so attractive? Everything is done in such a way as to make visitors feel as if they are in Europe instead of Asia. There are metal statues featuring townspeople (there were many disputes about a specific statue featuring a girl in front of the McDonald’s restaurant.

Questions such as ‘why is her belly exposed?’ were commonly heard), red lamp posts instead of the more traditional style found elsewhere, and a giant flip flop flower bed. More than that, everything is clean and fresh.

A real Parapet

“Real Bakuvians call it Parapet!” a taxi driver told me while we were stuck in a traffic jam. It was raining outside and the vehicles were beeping their horns all around. A song known as ‘Tut Agaji’ was pouring out of the loudspeakers. “You can recognise a Baku resident straight away. You, for example, are a Bakuvian, aren’t you?” I nodded in order to avoid an argument.

The issue of something ‘real, primordial, and genuine’ is a very controversial one.

In 1859 (when present-day Azerbaijan was divided into governorates that were part of the Russian Empire), a destructive earthquake hit Shemakha, resulting in part of the population moving to Baku. Shemakha province was later renamed to Baku province (since there was no capital city at that time).

Thus, it all depends in which part of history we draw the line and say: ‘This is where ‘real’ begins’. The same is true with Fountain Square. Before it became known as the Parapet, it had different names and looked different too. However, in the beginning it was just a wasteland.

Generally speaking, everything was a wasteland in the beginning, and the Spirit of the Lord hovered over it and saw that it was not good.

Fountains square: what was there in the past?

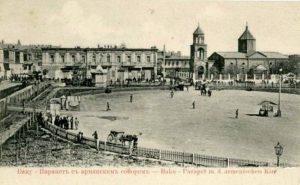

1860. Kolyubakin Square

Kolyubakin city governor ordered to ennoble the area beyond the city rampart. The square was named after him.

It was decided to landscape the wasteland and pave with stone the sections where a military band was supposed to stand and the troops would march. Qasim-bek Hajibababekov, a local architect, designed the square.

He was also a native of Shemakhi, where he used to work as a provincial architect. By the time he had almost completed Shemakhi master plan, the subject of his work was destroyed. It was he who suggested a ‘sun-shape’ design of a new square, which later influenced the entire image of the city center.

Under his design, the square became semicircular and the newly built streets branched out from it in different directions, forming the rays.

1900. The Sunny Square (in a bad sense)

The square landscaping turned out to be quite a labor-consuming process. There was no water supply system in Baku in the second half of the 19th century and the plants couldn’t strike their roots on dry Baku land without regular irrigation.

At the end of the century, it was decided to bring some beautiful, less pretentious sorts of trees from Georgia, then some rare species were brought from Europe.

But neither of them stroke roots without water. As a result, it turned out that all funds, allocated by the treasury for the square landscaping, were spent completely.

So, a monument to Alexander the Liberator, that was supposed to stand there, was never built. As for the name, by the end of the century it was called the Sunny Square, but that wasn’t due to its design, but rather because there was nowhere to hide.

In the mass media of that time it was also referred to as the Imperial and Alexander Square. And the Parapet, too.

1914. The Sunny Square (in a good sense)

The 1905 civil war in Iran triggered the second big wave of migration to Azerbaijan.

Baku had to receive refugees; the city population was growing and the authorities started thinking of possible sources of drinking water.

The construction of Shollar water pipeline, which is still used nowadays, was launched in 1910. The construction works finished by 1914 and a park with trees finally appeared in the Sunny Square.

In addition, the rest of the houses were built (and they still exist) in that period.

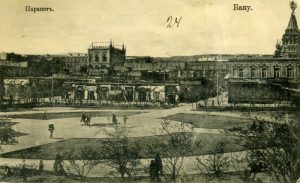

1920. Karl Marx Square

Then the revolution broke out. Afterwards, the Parapet was renamed into Karl Marx Square.

It was further landscaped and the military reviews were replaced with the Komsomol and pioneer events, theatre performances and political speeches.

The Communists also decided to erect a monument in the square (certainly to Karl Marx), but they were overtaken by an old curse, too.

As soon as the works were launched, the trees that had been planted before the revolution started massively drying up. And a search for more appropriate species started again.

1925. The Barren Garden

At that time the square was popularly named as the ‘Barren Garden’.

The area became quite dull, in general. The ateliers, shops and costly restaurants were closed and were replaced with the cheap ones with corresponding quality.

In the ‘20s, there were austere Soviet canteens and pubs, as well as certain Public Amenities Center, offering no less austere-style Soviet clothes.

1950. Fountains Square

It was in the ‘50s, when Ivan Tikhomirov, an architect, started a wide-scale replanning of the square. Some new fountains and really umbrageous trees appeared. The latter were featured in the background in Muslim Magomayev’s clip ‘My city-Baku’.

1984

Ragim Seyfullayev, an artist and architect, was the last person who carried out the soviet reconstruction of the square in 1984.

It was then that concrete slabs and asphalt were replaced with white and red stones, which ennobled the area. At the same time, some new fountains with long, low curbs, and without any architectural frills, appeared.

A famous fountain comprising numerous figures of characters of Nizami’s poems was also built at that time. And also, more new trees and tall palms were planted during the 1984 reconstruction.

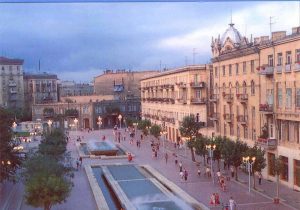

2010. Present day

The latest reconstruction of the square took place in 2010.

The square has acquired a more eclectic appearance: new futuristic fountains and curved lamp posts have been put side-by-side with à la Greek-style monuments and columns, tiny stone hippos and metal statues.

The trees have dwindled in number and the fountain with Nizami poem characters has disappeared. Some people are amused and proud, while others say, the local color and recognizability have been lost. It’s all relative.

We stopped at the Puppet Theatre. The taxi driver charged me AZN 10 (It’s daylight robbery! And he claims to be a Bakuvian!) and I headed to the centre, to that very square.

After a restoration in the mid-80s and another minor renovation seven years ago, the Fountain Square isn’t what it used to be. There are five fountains in the square, each of them ‘unique’ in terms of style, and there is even one featuring hippopotami. There are also plenty of round, curved, and shiny reliefs on them, and a bronze girl with an umbrella whose sheen has dulled in certain places from frequent touching.

All the aforesaid are probably modern symbols of the square, aka the Parapet.

What else is near and dear to our heart here?

What about the landmarks and phenomena that no longer exist? We collected a few preserved stories and asked Bakuvians what was interesting in earlier times at the Parapet. Along with common nostalgic examples such as the tram and a Dynamo shop, we discovered many other unexpected things, such as an elite brothel.

People’s memories of the square

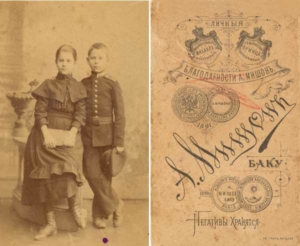

Mishon’s photo studio

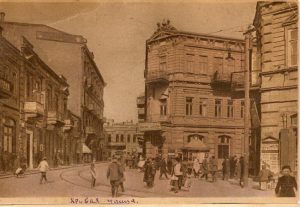

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Fountain Square became the very heart of the city. There were 30 photo studios in Baku at the time, and five of them fronted the square.

There were also numerous shops, boutiques, restaurants, French hat stores and the city’s best confectionery shop.

Mishon’s photo studio was the most expensive one. A regular photo with props amounted to RUB 5 (while a worker’s salary was RUB 10).

Brothel

If you walk down the square to Nizami street, you will find millionaire Musa Nagiyev’s house in a passage on the left side. It’s a building with beautiful monograms built in 1910.

There is also a small, plain building in front of it. There is no mention anywhere of what was inside of it, but this little building used to be a brothel.

How does this connect to the Parapet? It was probably called the Parapet not only due to its stone retaining wall (that was set at the end of the 19th century, fencing off the square), but also because expensive prostitutes gathered there.

That’s what old-timer residents told me many times. They said that it was ‘a couple for five’ – two for five rubles, which was quite a substantial sum in Tsarist times. But it was half the price of a photo in Mishon’s studio!

As far as the ‘notorious’ two-story brothel is concerned, some wall paintings of piquant content had been preserved there even from Soviet times. Moreover, judging by the layout of its internal structure, its evident that it wasn’t a residential house with separate apartments, but rather a building with ‘suites’ on both sides of the central hall.

The Bolsheviks casually covered up such ‘disgraceful’ paintings and put tenants in. One of the residents said that the shameful anti-revolutionary content would pop up here and there in ascetic soviet wallpapers.

A tram

It’s hard to believe now, but there were trams running through Fountain Square in Soviet times. The elderly say that the most convenient route was the one that ran down Communist Street (now Istiglaliyat Street), rounded the square and drove further along.

The tram closing down is something that ‘real Bakuvians’ particularly regret. It was a symbol of ‘international’ Baku, one that is gone forever, a symbol of a city where ‘everyone drank citro (Rus. lemon soda) from a special machine and even from one and the same glass ‘(on a side note, no one had ever stolen that glass or had been infected with any disease).

A fish store near the Armenian church

There is a large fish store with a pool right in the centre. In Soviet times there were fish swimming in the pool and they were caught and sold from there directly (along with the citro, shared glass and tram).

There was no such thing as a monopoly on sturgeon caviar, which is a sad phenomenon of the past few decades. Caviar, both black and red, was served in huge metal trays, and didn’t cost much. Here’s what a ‘real Bakuvian’ recalls about caviar abundance:

“I couldn’t stand black caviar. But it was believed that it was good for your health and it should be crammed into a child in huge quantities. Therefore, it was rolled into small balls for me, and I swallowed them without even chewing.”

Dynamo shop

- ‘It’s near the Dynamo shop.’

- ‘Where?’

- ‘You are a Bakuvian, aren’t you?!’

This shop, which traded in black shorts and tennis balls, as well as in brutal Soviet sneakers, closed shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thereafter the Ramstore supermarket opened, which was a real sensation at the time, and visiting it felt posh. The next owners, however, failed to advance their business, and thus it did not become a ‘landmark’.

Nargiz café

Nargiz café can also be regarded as one of the Square’s historical attractions. It was opened in the late 50s. Baku, like many other soviet cities, had few restaurants in general. However, with the onset of what has been called the ‘thaw’ period, people were given ‘some air’.

A couple of restaurants were opened in Baku, such as Nargiz, and a famous one on the boulevard called Shell. It is said that the Shell restaurant was named after a girlfriend of some party official who was in charge of the institution.

The restaurant used to charge double prices for certain dishes that were scarce and in demand. For example, there would be sturgeon and black caviar on the menu, but the prices were not indicated.

The restaurant also featured in the Soviet blockbuster The Amphibian Man, in an episode where a Latina performs the jazz composition ‘Hey, sailor, you’ve sailed too long!’

The passage

In the late 90s, the area between Musa Nagiyev’s house and the cherub house became a centre for trading in souvenirs and paintings.

Silver cutlery, handmade jewelry, as well as magnets and amulets, were available for sale here.

Mammad* used to sell his paintings here. They mostly featured battle scenes with ancient Azerbaijani heroes at the foot of the Maiden Tower and were painted amateurishly. However, Mammad also painted some good pictures for his own pleasure, but he ‘stored’ these at home.

Once, Mammad heard a voice in his dream, saying: “Don’t worry, Mammad, you’ll get rich soon. Just sit calmly and don’t make any unnecessary movements.”

However, years passed and Mammad could still be seen in the passage, with a glass of tea in hand, standing against the background of acid-green landscapes. Then, the municipal authorities decided that the passage looked sloppy and banned street vendors. Since then, it’s unknown whether Mammad’s prediction came true or not.

Rhapsody café

This café is from the 80s. Opened right in the centre of Fountain Square (i.e. in the Centre of the Universe, as Baku teens of that time regarded it), the Rhapsody café seemed to be a luxurious restaurant. Everything was a novelty, be it Coca-Cola in tall glasses, pizza, the self-service principle and the fast-food idea in general. McDonalds started operating in Baku only in 1999, but before that the Rhapsody café hosted birthday parties, dates and company feasts on some important occasions.

Later on, McDonalds assumed all those functions for a while. Then the time of ‘oil satiation’ came and everything fell into a new groove: people started drinking beer in pubs, McDonalds became a family fast-food restaurant and real restaurants for parties and dates were opened.

But one thing still remains unchanged: the Fountain Square, aka the Parapet, is the only place where you can ‘see and be seen’.*Name changed to protect the privacy of the individual.