Azerbaijanis talk about a most sensitive matter

Today we are doing something terrible – we think about other people’s money. We wondered how exactly the family budget of the Azerbaijanis from the different societal strata changed during the time of the cheap manat.

Samir and Leila were left without restaurants

Samir is a labor protection specialist in an oil company, while Leila is a freelance copywriter. They have one child – a small daughter.

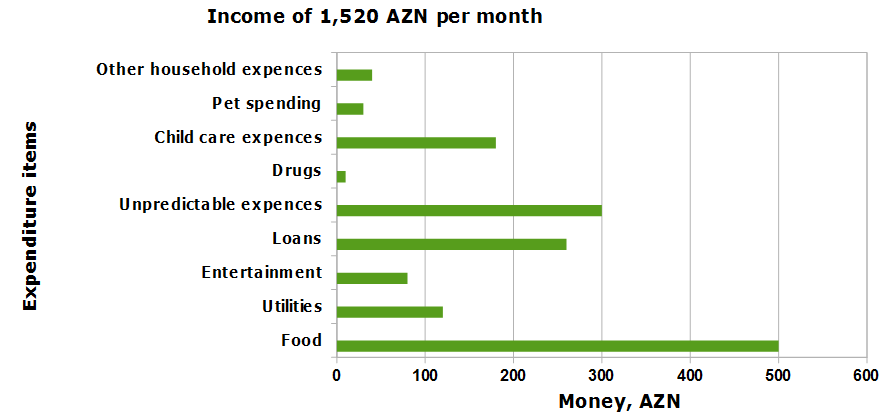

Their approximate budget is 1500 manats (about USD 875)

Accounting is easy on the Internet, in the Zenmoney program. They estimate their income as average, but in general, their financial situation does not appeal to them.

The house of Samir and Leila is on a small street not far from the Railway Administration office. The building apparently looks like a converted hostel that overlooks a two-story car-wash with little shops crowded around it.

The hostess waved to us from the window in the courtyard, so we go up to the required floor. There is a common corridor, from which there is an entrance to a small neat apartment.

“We were lucky, only we have a state mortgage out of all our acquaintances, that is, in manats. We pay 231 manats monthly. Last month, we paid 125 manats for the electricity, a disaster!”

“In the past, before the birth of my child, I wrote articles in different publications. The fee was 30 manats. Before the devaluation it was USD 40, now it is USD 19,” says Leila. “We have enough but we can not make any savings.”

After the devaluation of the manat a lot had to be given up: “I used to shop online, stuff, toys for myself, for the child. Now this is not affordable anymore. Before the crisis, when I did not have time to cook dinner, I could buy semi-cooked products – cutlets, sausages, etc. but now it does not work out. We stopped going to cafes. We can go out once a month to eat somewhere in a shopping center – mostly in the KFC.”

We try to keep a healthy diet, buy rye bread, red rice, our child constantly eats zucchini and broccoli. It’s all costly,” says Leila, “but at the same time, we do not buy soda or sweets – very rarely. Moreover, my husbands employer provides him with meals – also a saving.”

Samir and Leila try to wait for seasonal discounts when buying clothes. Big expenses are planned and coordinated: “Last month, the baby was vaccinated – which cost 200 manats. Next month we plan to change the water heater. Even the question ‘whether to buy a set of Lego or not for the child’ is also discussed.”

Previously, the couple went to Batumi for a rest. But this had to be abandoned because of the devaluation and comparative price increases in Georgia.

“We do not buy books – only for the child. Small pleasures? I recently bought cosmetics for myself for 30 manats. This is not much considering that it will last for a long time and on the internet the Ideal cream costs at least 45 manats.”

Ilgar and his family stopped eating meat

Ilgar Ahmedov is a car washer. He has a family of four.

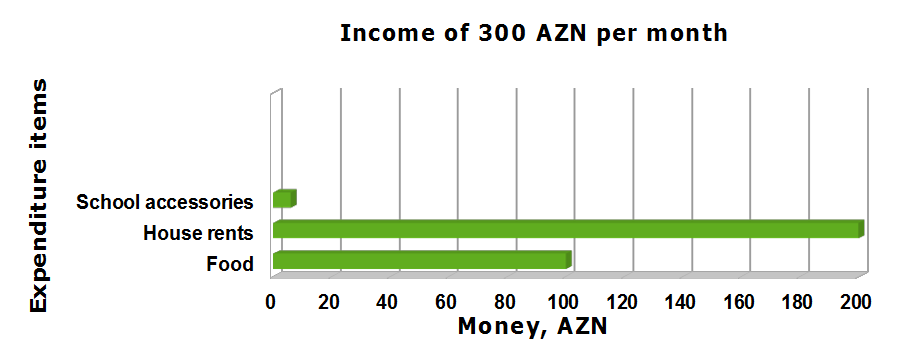

The budget is unstable – maybe 150-200 manats (88-117 $) and in good months up to 400-500 (230-290 $).

When waking up, the first thing Ilgar does is look out the window – is it raining? If it is rainy he will have to stay at home which means a loss for the family budget.

Ilgar is a car washer. Before, he was a shoemaker who worked in one of the local workshops. Good shoes, high quality and well paid. Then the local shops closed because of the import of cheap products from China.

200 Manats a month goes towards renting a one-room Khrushchev era apartment near the Narimanov metro station.

Although there is a house, there are only the most basic amenities for life. “Furniture from my wife’s dowry was worn out while we were wandering from one rented apartment to another,” says Ilgar. “We have no washing machine.”

Cars are not washed in the rain. Sometimes there are no clients for several days. If you are lucky enough, there is a “full service” – washing cars from outside to inside – and five to six customers, when can bring home 40-50 manats. Because of the unreliable earnings, in the “successful” months the family does not allow itself any extras. First of all they pay rent and for utilities, and surpluses go “into a reserve.”

It is impossible to plan a budget in such circumstances. Enough only for the most inexpensive food and household goods. “It happens that we do not eat for two or three months,” Ilgar says, “unless relatives, thanks to them, bring food.” There is no question of spending on clothes. Their relatives buy uniforms and school bags for the children. Our money is enough only for necessary stationery – notebooks, pens, books. Children’s birthdays are also celebrated by the relatives – they take them to entertainment centers and cafes together with their own children.

Ilness is a tragedy for the family. I have to get into debt to go to the doctor.

Has the devaluation made any impact on the family? “We do not have loans, we do not buy anything expensive, we only spend on food,” says the head of the family, “but if earlier I used to buy food for twenty days for 50 manats, now it’s only for ten. It is good that fruits and vegetables are cheaper in summer than meat, so this is how we get out from the situation.”

Ilgar considers himself a poor man. Due to the fact that he is constantly at work, there is no time to stop and think about the future. The future is tomorrow and preferably without the rain.

Sabina saves on Europe

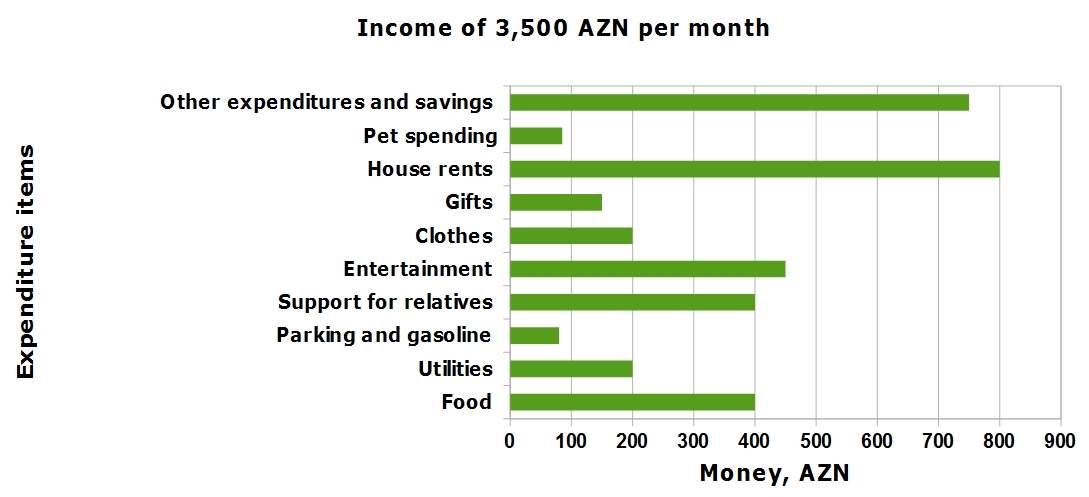

Sabina is a financial director at a branch of an international company. The salary is 3500 manats (about USD 2000 ). She estimates her income like this: “The highest bar in the average section.” There are three members of the family.

She keeps track of expenses in an accurate and scrupulous way in a program table – not out of a desire to save, but rather out of professional habit.

I’m waiting for Sabina at the exit of the business center where she works. She comes out lightly dressed. “Why do you not have a bag?” I ask curiously. “I live not too far from here now,” she points to the old building just across the road.We go in a cafe where everything is “simple but tasteful”: the bar is simple but stylish, panels on the walls imitate bricks. She removes a light coat and under it – modest clothes, no jewelry.

“Every week we go out somewhere,” says Sabina, taking a sip of coffee, “we can go to Araz (a relatively inexpensive cafe in the city center), they have tasty dishes there, but we also go to expensive places, such as Energy (a fashion club in Baku).”

“I’m buying clothes in Massimo Dutti, Zara. I do not really care about the brand, I do not understand people who deny themselves everything, save a few months to buy a brand name, but I think it’s better to spend once on a quality one than to buy five low-quality things. Just in these stores I can find something suitable to my style. I can go in both Next and Bershka, but I hardly find the right thing there,” says Sabina. “Well, the status obliges: you can come to work in an international company dressed casually, but this “cache” should be of excellent quality.”

“I do not consider myself a very rich person,” she says. “In my opinion, the middle class are those who do not save, who can afford a normal standard of living, travel abroad, live comfortably.”

Although Sabina received less before the devaluation – only 2,700 manats – she could afford much more. For example, traveling to Europe. Now, although her salary has increased, a trip has to be prepared for several months in advance. She has to choose budget tours, and instead of booking a hotel, she has to opt for an apartment on Airbnb.

Conclusions

The people shown here are only a part of the respondents. In fact, there are more of them and this allowed us to make some generalizations.

[yes_list]

- People with an income of 1,000 – 2,000 manats (about USD 900) call themselves middle class, although they admit that after the crisis with such salaries they can not make any savings at all. The average class no longer goes to restaurants, cultural events after the devaluation, they do not make savings, do not travel outside the country at their own expense. Nevertheless, they try not to save on the pleasures and education of their children.

- The lower class did not feel much of a difference: “we lived poorly and continue to live the same way”. These people used to allow only the most necessary things for themselves. Azerbaijani poor people are vegetarians by force. Most of all, they are afraid of diseases and regular payments such as house rent.

- Apparently, the highest salary level in Azerbaijan does not exceed 3,000-4,000 manats (USD 2,000 on average). At least, people with this level of income are still willing to share information about the contents of their wallets. But even this above-average salary ceased to provide people with the usual degree of comfort after the crisis.

[/yes_list]

The average salary in Azerbaijan is 466 manat (USD 280), according to the latest data of the Statistics Committee.

The minimum salary is officially set at the 116 manat ($ 68) level, that is, you do not have the right to pay less to an employee.

The maximum salary, according to official statistics, is 2,500 manat (approximately $ 1,500). However, the real income of the upper class exceed this bar and are lost somewhere in the heights of the shadow economy.

It must be remembered that the income of all other classes do not only consist of a salary, therefore one can not rely on official statistics to understand how much Azerbaijanis actually earn.