Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict: how wars can overturn one's worldview

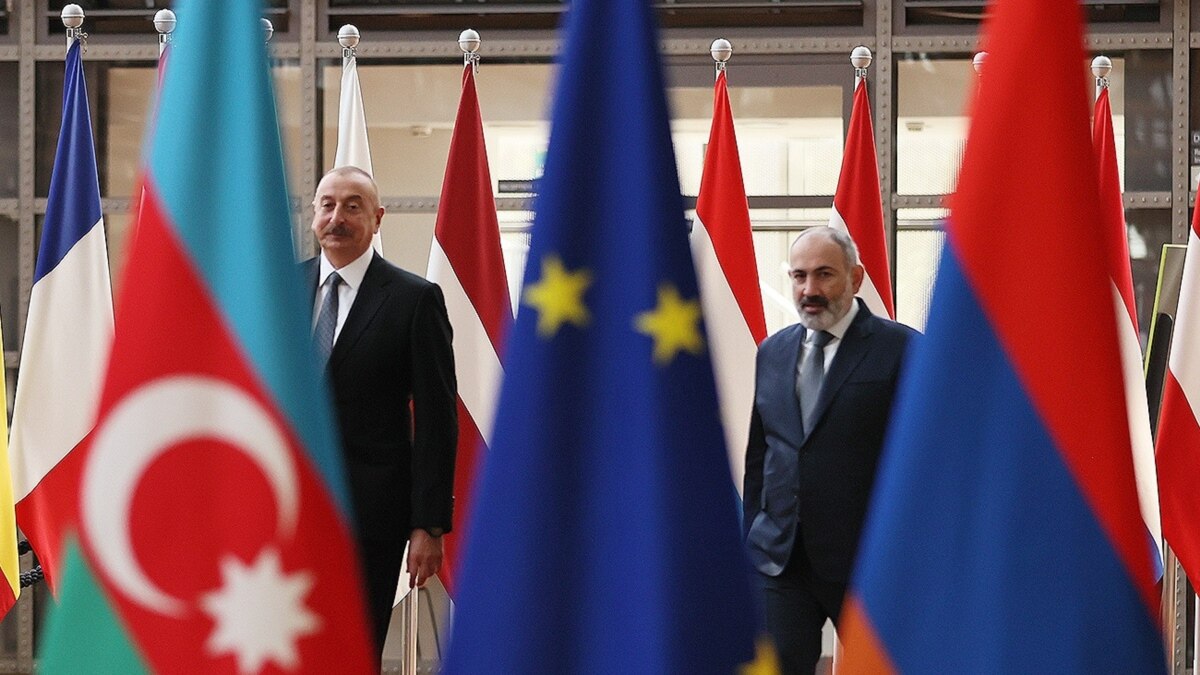

Will Armenians and Azerbaijanis be able to live together and treat each other as equals, or will they remain enemies, trying to solve the conflict by force? Important decisions are usually made by governments and politicians, but, often, a lot depends on the position of the ordinary citizens, especially when it comes to the prospect of peaceful coexistence.

These two stories are about how and why people can change their outlook. Both respondents are Bakuvians, old enough to witness both of the Karabakh wars – the one in 1991-1993 and in 2020.

Aydin Mammadov, 65 years old

In Soviet times, I had many friends from different countries – who didn’t? There were also Armenians among them, especially since there were quite a few of them living in Baku at that time. Some were good neighbours, others were good comrades.

Therefore, when the first Karabakh war began and all those stories appeared about how Armenians had been killing our children and tormenting our women, I did not want to believe it. It was also said that there were a lot of criminals and foreign terrorists in their army. [I thought] that this explained all the stories about horrible atrocities that had been committed.

Years passed, and the pain from everything experienced subsided. Work, family affairs – somehow you get used to ordinary life and you forget about everything that happened.

So many years had passed that I no longer believed that I would see our lands liberated.

But I was sure of one thing: today’s youth was not like us. They are looking up to the foreign countries, they become pacifists. Therefore, I thought that these young people would be able to resolve conflicts in a humane way, especially if there were also young people like that in Armenia – and those same criminals from the nineties were either old or had been burning in hell for a long time.

And then the second war began.

It was very hard for me, even though my children were not at the frontline, how could I not be worried? I didn’t want it to be like this. I thought maybe everything would be limited to one area – they would surrender quickly and no one would kill each other. I drank valerian every day.

But the day when the bomb fell on Ganja changed everything. This time I could not justify what I saw on the Internet, and it was no better than in the nineties. A soldier kills a soldier – that’s always been the case. But not a child. When I saw a photo of a father carrying his child to bury them, I felt horrible.

After this war, I had no faith left that we could live together with the Armenians, like we did before the war.

Kamran Guliyev, 42 years old:

As a child, I was a big chauvinist. One boy lived in our yard, let’s call him Jeyhun for conspiracy. Actually, he was only a quarter Armenian, but for some reason we considered him Armenian. It was a conflicted, capricious child, and my family attributed his behaviour to his nationality.

I remember how I gathered the children who lived in my yard in a circle near the garage, I preached to them that it was the Armenians who started the Karabakh conflict. It felt like a a very original idea to me, and Jeyhun’s bad behaviour fit perfectly into my theory.

I was about 9 back then, for the next ten years I continued to repeat what I kept hearing at home: that Armenians had occupied Karabakh, and it was no different from our neighbours, one day, making a hole in the wall and taking away one room from us “just because they can”.

A small fly in the ointment of my patriotism was my crush on a girl named Sargsyan from the fifth floor, who left in the early nineties, and to whom I wrote long letters, but never received a response.

Then, having read books about the Holocaust (and having read books in general), I came to the conclusion that defining a person by their nation is bestly and unworthy of a concious being.

Then there was another ten-year period, when I thought that not every Armenian was an enemy, and that it was better to avoid war, but if they drafted me, I would go to defend my Motherland, because I was a man.

And then it so happened that I began to read the news and study history. And it turned out that all this time I was an idiot. The war was absolutely unnecessary, there was no point in it. And all this conflict, all this ‘pulling’ the earth back and forth – was also useless.

It was possible to come to an agreement, to solve the problem, but instead, people hated, killed, died, incited others, and spat poison on social media.

Until now, what is most shocking is not even the immorality of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, not these political games and dancing on the bones, but rather the boundless stupidity and boundless pathos of this idea of “dying for the Motherland”.

What makes you think that it will be pleased to see you dead?

Of course we can live together – we just don’t want to. Because it’s hard to love, it’s hard to think, but it’s easy to hate and fight and everyone knows how to do it”.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union