Armenia: coronavirus vs. free speech

Government bends under public pressure and removes stringent restrictions on journalists during a state of emergency

Due to the rapid spread of coronavirus, the Armenian government declared a state of emergency on March 16. Among other restrictions, the decree imposed limitations on journalistic work, and even on social media posts.

Distributing any information that was not from an official government source was prohibited. This decision evoked not only surprise, but outrage, both in the Armenian journalistic community, and society at large.

What restrictions were imposed

● Any publication about coronavirus, namely: reports on the number of infected and isolated, new cases, sources of infection, the state of health of patients in both Armenia and abroad, should cite information provided by the commandant’s office, a structure created by the government to monitor the situation during a state of emergency.

● The decree also prohibited “material that could cause panic among the population,” but with no clear definition of what information falls into this category, which raised red flags for journalists.

- Armenia to introduce fines, prison sentences for violating quarantine during state of emergency

- Armenian gov’t offers stimulus package to help mitigate corona crisis

- Armenian PM drops in by phone and asks – how’s life in the times of corona?

Immediately after the state of emergency was declared, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated that the restrictions would apply exclusively to information about coronavirus:

“The media restrictions will not touch on other issues. There will be no other restrictions on the activities of journalists. Criticism, and even accusations against the government in connection with this policy will not be censored.”

The harsh criticism of the decision forced the administration to make some changes. In particular, it was initially decided that restrictions would not apply to information that is published or provided by:

- officials,

- heads of foreign governments,

- international organizations and their representatives,

- diplomats who are accredited in Armenia.

If the agency did not delete objectionable information within a day after publication, they would be given a fine of 100 to 400 thousand drams (approximately 200-800 dollars).

Examples of restrictions and the reaction of journalists

Immediately after the state of emergency was declared, the commandant’s office began to contact news editors and ask them to remove articles that used non-official sources.

The newspaper Hraparak, for example received several requests to remove material, including an article on prisoners who were upset after being unable to receive packages sent from home, including cigarettes, due to the coronavirus.

The government has decided to ban package deliveries to closed institutions in order to prevent the spread of coronavirus. This information was available in the public domain. But newspaper complied with this request and deleted the publication.

The newspaper Aravot also received a letter from the commandant’s office. The editor-in-chief of the publication, Anna Israelyan, had to edit an article which included commentary on the coronavirus from Russian political scientist Vladimir Solovy:

“There were a points that would be considered problematic in the interview, however, we reprinted only the part where he said that the Russian authorities are hiding the true number of coronavirus cases. In the same article, we quoted Prime Minister Pashinyan’s statement that some countries do not publish exact figures. After we published the story, I got a call from the police. I’ve been working from home, and a police officer called me and demanded that I delete the article, otherwise I’d have to pay a fine of 500 thousand drams [$1000].”

The commandant’s office forced many media organizations to take down information, but not everyone was in a hurry to fulfill this requirement. With each new incident, the journalistic community grew more indignant. Journalists and experts openly stated that the government’s restrictions of free speech were unjustified.

10 journalistic organizations issued a joint statement calling on the government and the commandant’s office to “immediately nullify” the restrictions on the work of the media.

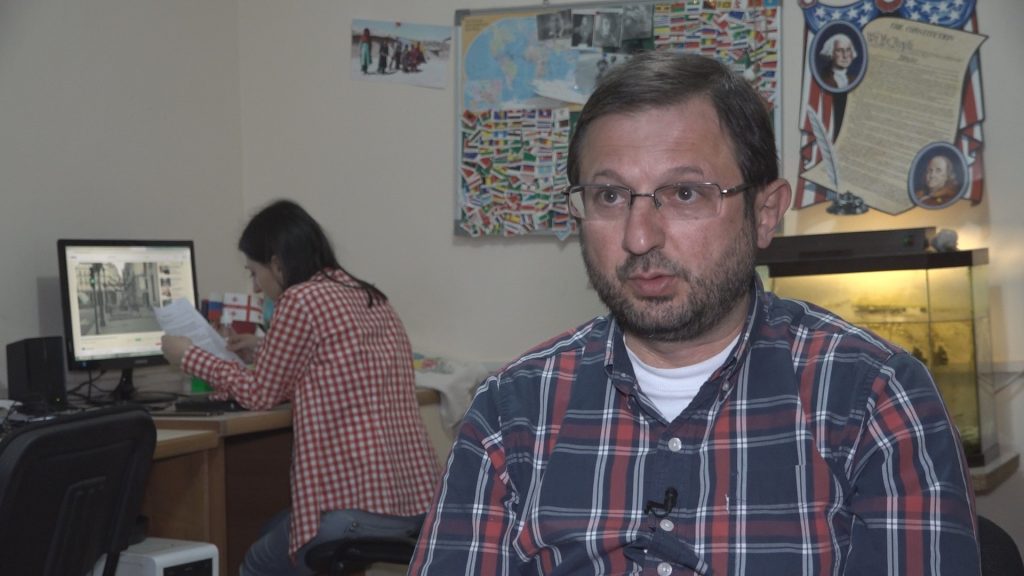

Head of the Yerevan Press Club, Boris Navasardyan, is certain that the tough and unreasonable measures taken by the government were unnecessary:

“The situation in Armenia doesn’t require these sorts of strict regulations. They could have avoided restrictions entirely. And if they are going to impose restrictions, they should be lax and shouldn’t limit the information we spread.”

What happened next

The commandant’s bans led not only to massive discontent, but also to numerous incidents.

For example, Armenian media could not reprint information from international publications about celebrities or famous figures who had contracted coronavirus.

The World Health Organization updates data on infected and dead people much more slowly than other reliable sources. As a result, the Armenian media were forced to either give outdated information, or to stop publishing coronavirus statistics completely.

The situation progressed to the point where officials themselves began breaking the law. In particular, the mayor of Hrazdan posted information about the first reported coronavirus case in the city on social media, which he had no right to do. This information was supposed to come from the commandant.

Public pressure forced the government to reconsider its decision once again. And this time the relief was palpable.

Теперь разрешается любая публикация о зараженных, изолированных и самоизолированных гражданах Армении, информация об эпидемиологической ситуации.

Now, all publications about the epidemiological situation, including number of infected, quarantined, and self-isolated, are permitted. However, if the commandant’s office wants to refute or clarifies any information, it must do so within two hours after the initial publication.

Armenian publications are still allowed to reprint material about the coronavirus from international sources, as long as they indicate the country of origin in the headline.

The government also decided to repeal the provision on materials which cause public panic. Journalistic organizations considered these changes to be objective and sufficient for a state of emergency.

Despite this, there is still a clause which states that any refusal to delete prohibited information within a 24-hour period will result in a large fine ranging from 500-1000 times the minimum wage ($ 1000-2000).

“Thank God that these restrictions were short-lived. The amendments create more favorable conditions for journalistic work. Even if there are restrictions, they are rational and do not prevent impartial coverage on coronavirus,” said Ashot Melikyan, Chairman of the Committee to Protect Freedom of Speech.

The reason for the restrictions is unclear

Media experts, journalists, and international organizations continue to discuss why the government has chosen to restrict freedom of speech.

Director of Information and Socio-Political Programs at Yerkir Media TV Gegham Manukyan believes that the authorities saw journalists as an obstacle in their fight against coronavirus, while the journalists themselves were determined to cooperate.

“It was difficult from the very beginning when the state of emergency was declared. In a few countries, the press was immediately put under the gun by the government or the commandant. And there was this moment of managerial ineptitude, when no one knew what to do. They formulated the restrictions in such a vague way that they themselves did not understand how the press should work. And the media didn’t know how to behave.”

The government decision provoked a negative reaction from the OSCE.

Harlem Désir, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, said he was sympathetic to the government’s steps to avoid panic and attempts to combat misinformation during the epidemic:

“At the same time, the media play a decisive role in providing important information to the public, and countering false news about the epidemic. The law should not impede the work of journalists. The restriction on any information not provided by the authorities is excessive, and restricts freedom of the press and access to information.”

The head of the Yerevan Press Club, Boris Navasardyan, thinks that this situation may be reflected in the annual reports of international organizations the Press Freedom Index.