Armenian Yazidis object to their children being forced to say Lord’s Prayer at school

Sharfadin: the religion that is passed down through word of mouth

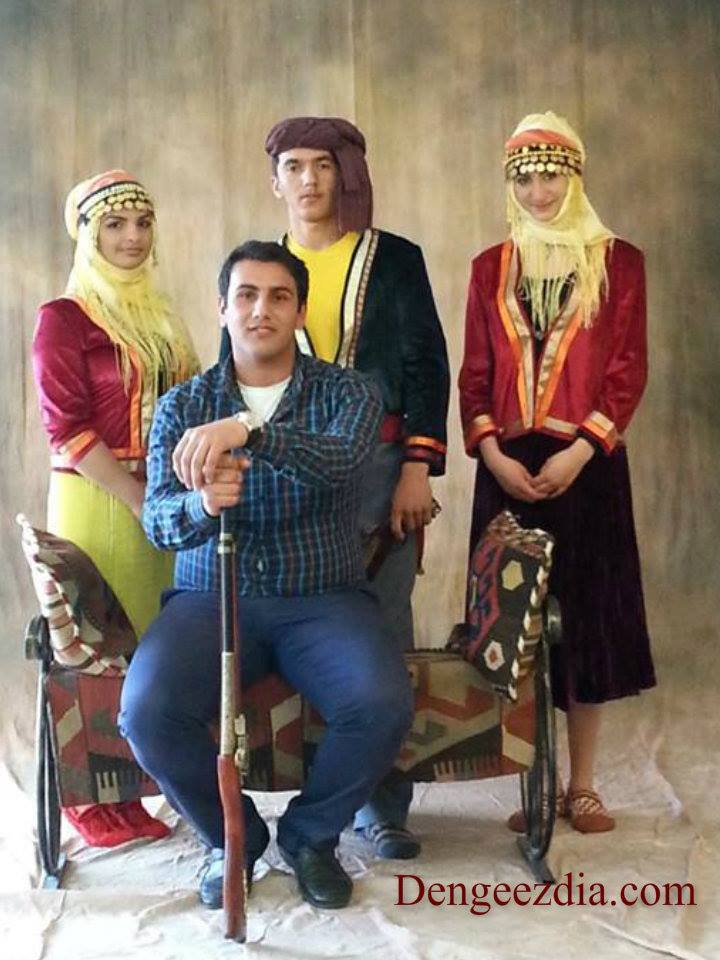

Hamlet Smoyan is a native of Armenia, an ethnic Yazidi and a follower of the Sharfadin religion. He lives in the Araks village near Yerevan. There are 450 families in the village, of which 10 are Yazidi households.

Hamlet has never given deep thought to his ethnicity. He is a Yazidi and that’s it: a progressive-minded, well-educated, traditional Yazidi. However, he started thinking about his religious faith when he was a teen.

“When I was a child, I knew that we had our own religion, but many questions related to it remained unanswered for me. I was a schoolboy when the ‘History of the Armenian Church’ was first introduced in the curriculum in all public schools across Armenia.

“Initially, the classes were delivered by an expert from Echmiadzin [i.e. a clergyman. Echmiadzin accommodates the residence of the Catholicos of All Armenia and the main cathedral of the Armenian Apostolic Church – ed.]. He was later replaced with a history teacher. We were required to say a prayer before the class started. I knew very little about my religion at the time. My religious awareness was also very low. I would stand up and say the Lord’s Prayer together with other students,” says Hamlet.

There are 10 ethnic minority groups in Armenia, with the Yazidi community being the largest one. According to data from the 2011 census, there are 35 272 Yazidis in Armenia (unofficially their number ranges between 45 000 – 50 000).

Ethnic minorities seldom report when they are discriminated against. However, there were a few occasions when they loudly expressed their discontent. For example, when some representatives of the Yazidi community complained about their children being forced to pray at school. The Yazidis suggested that the ‘History of the Armenian Church’ subject should be made optional so that the rights of non-Christian students were not violated.

In this regard they appealed to government officials, including to Armen Ashotyan, when he served as the Minister of Education. The latter responded as follows: “Those who oppose the ‘History of the Armenian Church’ subject are just western grant-hangers.”

“We also addressed the Catholicos with regard to this issue. He in turn said that the Echmiadzin [i.e. the Church] didn’t require students to pray because prayer wasn’t a part of the curriculum, and the teachers who underwent training in teaching this subject didn’t receive such instructions either. Then we came across the syllabus that clearly stated that a class should start with the Lord’s Prayer,” said Hamlet.

He believes that Yazidis are not subjected to discrimination at the state level. Although there is no discrimination, there isn’t any state assistance in the matter of preserving their religion either.

“The Yazidis are facing serious problems in terms of preserving and disseminating their religion. We have neither written sources nor any literature about Sharfadin. Information about it is communicated only verbally. It is passed down by representatives of the Yazidi castes of Sheikhs and Pirs.

“Since it is disseminated orally, the essence and principles of this faith undergo certain changes and are even distorted sometimes. This raises many questions among the Yazidis that remain unanswered, or people find answers in other faiths or teachings,” says Hamlet.

When it comes to preserving the history and language of the Yazidis residing in Armenia, the only contribution the government made was that it helped in making Yazidi school textbooks. They were introduced in 25 public schools where there is a teacher and a sufficient number of Yazidi students to form a class.

The Yazidi language is mostly taught in rural schools and in two schools in Yerevan. However, there are more than 7 000 Yazidis in the capital. The quality of school textbooks is far from perfect, there are very few teachers, and their salaries are extremely low.

Hamlet and his fellows from the Sinjar National Yazidi Association have brought a couple of books about national religion from Iraq, which is the Yazidi spiritual center. They translate books for Sunday school students at their own expense and with their own resources. The school is funded by the Sinjar Association.

“The problem doesn’t just lie in the lack of governmental support in translating and publishing religious literature. The most serious problem of all is that in different countries worldwide the Yazidis speak different languages and they are influenced by cultures that differ from one another.

“The picture also differs from region to region. For example, in Georgia there is a Yazidi shrine, spiritual leaders who perform their mission well and there is a high level of awareness of faith-related issues in the community. As for Armenia, there is a Yazidi shrine in Aknalich village, though the latter hasn’t become a spiritual center for the Yazidi,” said Hamlet.

There are differences in the Yazidi community on the issue of preserving their national identity and faith. Representatives of the older generation believe that everything is fine and prefer to remain silent and not pay attention to problems. Hamlet hopes that people like him will manage to change the situation. He believes that the progressive-minded and educated youth will be able to integrate into the Armenian society without losing their national and religious self-identity.

“My brother is in the army now, where it is also customary to pray before meals. During the prayer my brother stands up, like others do, though he doesn’t pray or cross himself. The reason is that a well-raised person should respect not only his own faith or religious views, but also those of other people,” said Hamlet.