A story of a clay donkey that survived Karabakh war

Children and the Karabakh war

In the living room of doctor Hayk Hovhannisyan in Yerevan, there are about a dozen different souvenirs on a TV shelf, among which a small donkey stands out. Made of reddish clay, it looks unusual, as it was clearly not made by a professional.

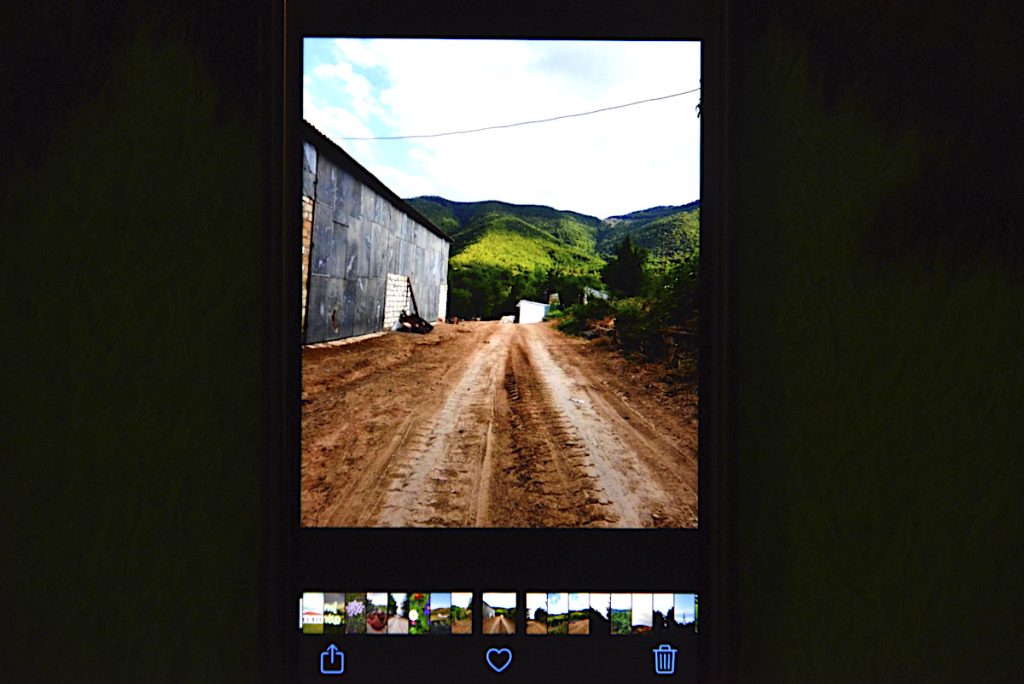

Hayk found this figurine in an art school in the village of Tog in the Hadrut region, where, in addition to it, there were dozens of clay bears, horses, and cows.

The donkey was lucky: it migrated to Hayk’s backpack and eventually reached Armenia safely.

- Life as an immigrant from Karabakh – ‘if I could go back to the pre-war past, everything would have turned out different’

- Armen and his ‘Aqua World’ in Stepanakert

- Blog: Police baton and memories of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War

During the war, Hayk worked in a hospital in the Jabrayil region. The whole hospital retreated and reached Tog, from there to the Red Bazaar and, finally, to Stepanakert (Khankendi).

And in the midst of the war, Dr. Hayk, who did not kill, but saved people, put this small figure in his backpack.

When I saw it on Hayk’s TV shelf, I thought: who made the donkey? What if they are looking for it? What if it matters to this person? And so I decided to find the person who made it and write an article about it.

Several months passed, but for various reasons I could not start looking for an unknown craftsman. Besides, I did not know who could help me.

Finally, I was able to find Grigor Avetisyan, the owner of the Kataro winery, which was located in the village of Tog before the war, and he gave me the phone number of Susanna, the director of the art school.

Susanna kindly listened to me, then sighed and promised to help, although I understood from her voice that my chances were close to zero. She said that she would try to find out who made the donkey, but she did not promise that anything would come of it. The children who attended school are now in different cities in Armenia and nobody knew who made the donkey.

I decided to wait. Susanna quickly found the leader of the group of young sculptors and asked me to send the photograph of the donkey I had. He promised to call back in a month, but the call came the next day.

When I saw the inscription “Susanna Tog” flashing on the phone screen, I realized that the author of the donkey was found it.

It turned out that his name was Kamo, he was 14 years old, and he lived in the city of Stepanavan, in the Lori region, in northern Armenia.

But I had things to do again. In a word, a year passed before the editor, photographer and I went to the north. Dr. Hayk couldn’t join us, but he gave us a donkey. However, he demanded that I be very careful with him and bring him back to Yerevan.

Kamo with his five sisters and a brother, parents and grandmother were preparing to see reporters. The town greeted us with a desperate mixture of slush and rain. The pink jackets of Kamo Varduhi’s mother and his six-year-old sister Narine contrasted with Stepanavan’s dull and monotonous appearance.

“For ten days now, Kamo has been telling me all the time: “Mom, call, ask when will they arrive”. I explained to him that they are busy people, be patient”, Varduhi said, escorting us through the wide courtyard to the house.

Neatly laundered linen is hung in front of the porch. Slippers are stacked at the entrance, by which you can guess the approximate age of the children and their favorite colors.

We undress and enter. In the villages, it is customary to take off your shoes, in Yerevan it is not.

In the middle of the living room, by the hot stove, sits Novella, Kamo’s grandmother. The young sculptor himself meets us in the middle of the room. We get acquainted.

Shy, with a silent smile, he watches as I take the donkey out of my backpack. Kamo picks up the figurine, looks at it, and confirms that it is indeed his donkey.

Then he puts the clay animal on the table and takes a picture of it with his phone. I’m asking:

-Are you not upset that I have to take it back?

-No, why would I be? I will make a new one.

Our photographer Vaginak, who, apparently, was expecting a completely different scene and was guessing all the way what the meeting would be like, began to photograph a donkey standing alone on the table.

Kamo says that if there is clay, he will make many donkeys, bears and horses. He studies at an art school in Stepanavan, but they do not work with clay there, they only draw.

Of course, life here is not like what it was in Toga. But he has adapted to the new place so much that he even speaks with a Lori accent.

We drink coffee, and discuss world events. The children, who take turns returning from school, also take pictures of the donkey. The story, which I conceived as a description of the long-awaited “meeting” of Kamo with his work, obviously does not work out.

I brought the donkey to Stepanavan, put it on the table and wanted to see it pulling some strings, perhaps make the whole family happy. Maybe it would evoke memories and nostalgia.

Instead, I saw people who left the past in the past. They have adapted to the new life and believe that returning to Artsakh (Karabakh) is dangerous for children.

A family with seven children should look into the future, and not live in vain hopes for who knows what.

We drink coffee and it kind of brings us closer. I ask: “And if the Azerbaijanis say: come, we will live peacefully on our land. Will you come back?”

The question took Kamo’s parents by surprise: “How? To go and live with the Turks? (Many people in Armenia call Azerbaijanis Turks – ed.) It’s dangerous! Do you know what they’ll do?”

But the grandmother shakes her head and recalls that in her youth she lived normally next to the Azerbaijanis in Toga. One of the episodes that she told seems to me, a man of the generation of independence, strange and even ridiculous.

So much so that I even begin to think that Novella just made up this story.

And she said that her mother-in-law had six children, and all six died. Then the Azerbaijani neighbors suggested that she name her next child with a Turkish name so that the hardships would end.

A boy was born and he was named Zahid. He grew up and married Novella. And the Azerbaijani neighbor, after whom the boy was named, became a “kavor”, that is, a godfather at their wedding.

Of course, not in the church and not in the registry office, but that’s what they always called him.

Novella knows the price of living with Azerbaijanis well, “she has seen both good and bad”, she says.

But how many generations must change in order to be able to live together again? Shaking her head, she says it’s too soon to think about it.

After staying with this Hadrut family in Stepanavan for about three hours, we return to Yerevan. I saw a family that, having lost their home, livelihood, and land, does not want to live in suffering and longing for Toga.

They accepted reality. And if they didn’t, it would be very difficult. They have seven children and they have to live.

Upon returning to Yerevan, I took the donkey to Hayk. He carefully took the figurine and put it in its place – by the TV, where it had been standing before.

“He reminds me not of the war at all, but of how desperately we all wanted to live during the war. Not even live – just not to die. Do not die at any cost”, said Hayk.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union