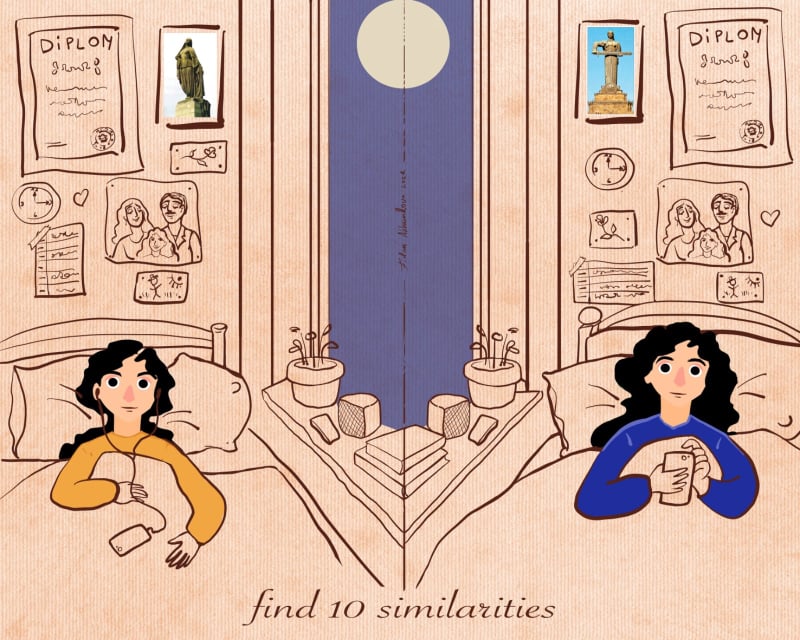

A girl named Haykanush, or find 10 similarities

With the help of animation, an artist wants to show the degree of similarity between the Armenian and Azerbaijani peoples and help them get rid of the “image of the enemy”

Fidan Akhundova is an artist from Baku based in Berlin. Having recently managed to completely get rid of the stereotypes about Armenians, she helped others to follow the same path. Now Fidan is working on an animation project dedicated to demonstrating to the Azeris and Armenians how much they have in common.

“Like most residents whose childhood fell in the 1990s, I heard a lot about how cruelly, barbarously the inhabitants of Khojaly were killed; I saw footage of those events, listened to the monstrous stories of adults.

It cannot be said that hatred has grown in me, but prejudice has grown nonetheless.

Living in Baku, I never met Armenians, did not communicate with them, and it does not matter at all what modern Armenia and the people there are like. And if somewhere on the Internet I saw a surname with the ending “-yan”, I would involuntarily feel rejection and fear on the verge of panic.

Khojaly is a city inhabited by numerous Azeris, where in 1992, during the first Karabakh war, more than 600 residents of the city were killed (485 according to the independent sources), hundreds were wounded or captured. The Khojaly tragedy is considered in Azerbaijan the bloodiest episode of the first Karabakh war. Azerbaijan is pushing the workd to recognize it as a genocide. According to the position of the Armenian side, the Khojaly massacre was organized by the Azeri opposition to overthrow the government. The tragedy is used as an argument by the Azerbaijanis who support the notion of a “vendetta”. In response, the Armenian side cites massacres in the city of Sumgayit in 1988, as well as the Armenian pogroms in Baku in 1990. You can read more about this here.

The first time, I seriously thought about the conflict and tried to make sense of it in my early twenties, when I was teaching children art part time. Once, soon after the anniversary of the Khojaly tragedy, one of my students came up to me and said that she hated Armenians because they had killed our people.

I knew where she had got it from – it was probably in her kindergarten where she was taught about who Armenians were and how they should be treated. But hearing this from a five-year-old girl was very unpleasant and frightening.

And then, succumbing to some impulse, I began to invent a story about a girl called Aykanush, who had the same curls and dark eyes, and who was also learning to draw and whose mother read her books at bedtime. And in the end I added that that girl, so similar to my student, lived in Armenia.

It is unlikely that this had a special effect, but I hope this made her doubt at least a little bit that all Armenians, without exceptions were monsters and murderers who should be hated.

Even for me, the real understanding of this was still ahead.

At the age of 25, I moved to Germany on a scholarship. I completed a master’s degree in art, and entered the pedagogical faculty. One day at a meeting of fellows, I started talking to a Russian-speaking girl. who turned out to be Armenian.

When I realized who she was, she got very tense, and so did I, but we still managed to smooth it out and part ways peacefully.

It was my first experience with a “real” Armenian. The next time such an opportunity appeared was a few years later.

When the second Karabakh war began, I was at such unease. Even though my Motherland did not meet many of my spiritual needs, even though I left it, and felt good in Berlin, still, at that moment, it was impossible to remain indifferent. It hurt too much to think that people were dying there, suffering and living in fear.

I wanted to talk to someone about this, and a friend recommended to me one group on Facebook in which Armenians and Azerbaijanis communicated in a normal, ‘human’ way.

I joined that group, and it helped me “ventilate” my mind. For example, I learned that some of the terrible myths that propaganda in Azerbaijan taught us were nothing more than myths. In turn, Armenians learned about some details of the same Khojaly tragedy, which had been previously unknown to them.

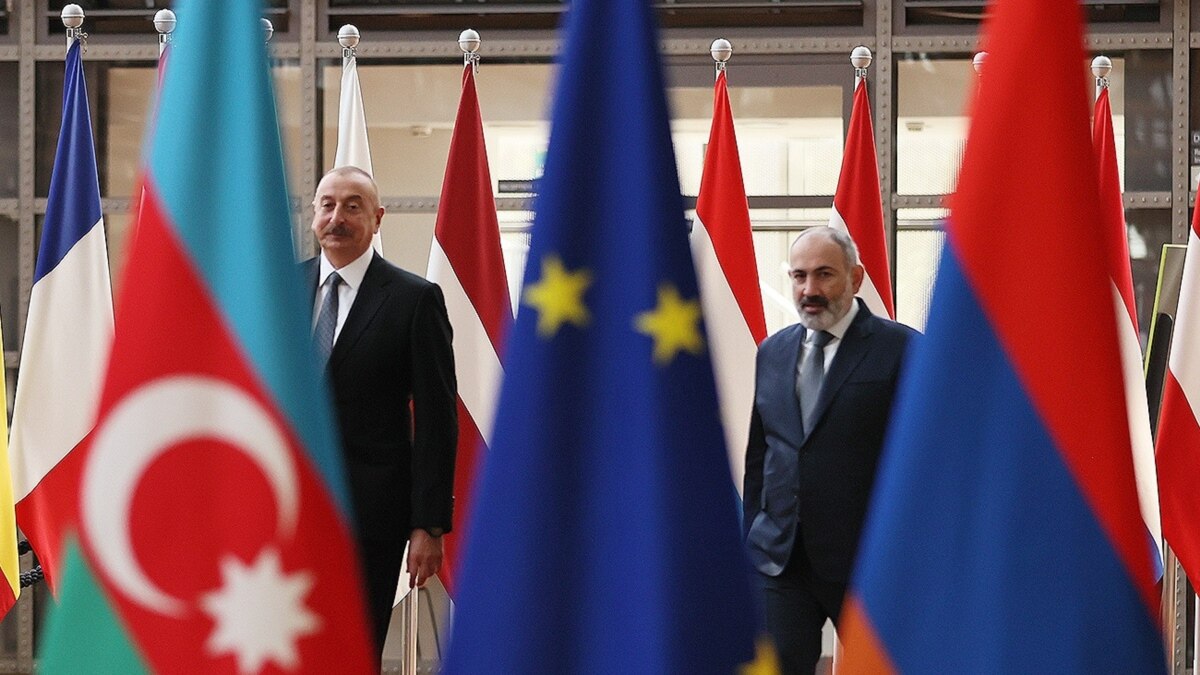

While discussing the past and comparing the information we had, we started to discover the facts that were unpleasant for us (Khojaly for them, and Sumgayit pogroms for us). We started realizing that our peoples had been turned into enemies by those who benefitted from it. We also understood that one cannot just blame the other side for everything and refute everything else.

The Khojaly tragedy is a very serious trauma for Azerbaijanis. But it is wrong to build a cult of hostility towards the whole nation for what the nationalists did back then.

We even met a few Armenians from this group who live here in Berlin. And I saw wonderful girls with whom I have a lot in common. In fact, I met a girl named Aykanush, whom I myself once invented.

After that, the veil of propaganda finally fell from my eyes, and the “image of the enemy” melted away.

So the idea arose to make an animated movie and, using the example of two families – Armenian and Azerbaijani, to show the similarity between the two peoples. I collected information about Armenian society, about the daily life of people and drew parallels with Azerbaijanis.

In theory, the viewer should not have a window, but rather, a mirror open for them, looking into which, they will understand how similar we are to each other, how similar our problems and our mentalities are, although we do not notice it straightaway.

The process of creating animation is very laborious, and I do everything myself, so it will probably take two years. For me, this is also partly an attempt to drown out the guilt that I feel for living a completely prosperous life in Berlin, while my compatriots in Azerbaijan have many problems of a very different nature, including the war.

The only contribution I can make to the resolution of the Karabakh conflict is my creativity. Although, of course, art – be it animation, books or whatever – is not able to resolve this kind of conflict.

Creative people do this primarily for themselves. In the best case, their work will make hundreds of people think. But nothing more than that.

Only politicians can resolve the conflict, and I have no particular illusions about them. Yes, and state propaganda will always be stronger than marginal peacekeeping projects.

But again, I do what I can because I want to do something. First of all, for myself. If it affects someone else, it is even better”.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union