Op-ed: War outcomes and the ‘winner complex’ - what does the victory mean for Azerbaijan

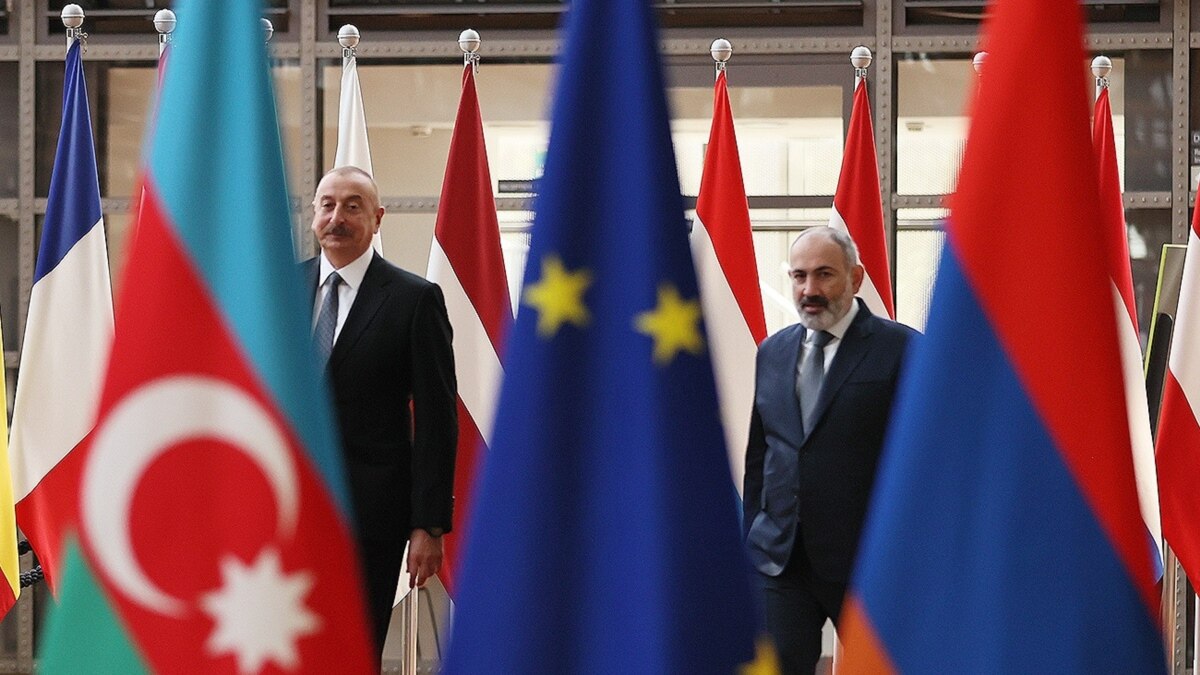

Almost six months have passed since the end of the Second Karabakh War. The war surprised everyone with its scale – few expected that it would end with the overwhelming advantage of the Azerbaijani army and the consequent return of all regions outside Nagorno-Karabakh. The war once again confirmed that the topic of Nagorno-Karabakh at any time and under any circumstances will make one forget about all the socio-economic problems and shortcomings of the political system, and the fear of going against the established opinion of society will force the irreconcilable opponents of the government to compete in support of the authorities.

The results of the 44-day war can be interpreted in different ways, but one thing is for certain – a new political situation has developed, which raises an important question – what next?

Until now, state propaganda has mainly relied on the resources of mourning, heroic struggle and forced retreat, sometimes under pressure from external forces, sometimes as a result of betrayal.

Now the list of resources has been replenished with unconditional triumph and victory, which can be literally physically touched and imbued with the spirit of total superiority over the eternal enemy. Appropriate conditions have been created for this and the War Trophy Park in Baku is the best example of this. Here you can see the figures of Armenian soldiers with symbolic grimaces on their faces. Both old and young will forever remember defeated opponents just like that.

This raises another question – will the enemy remain the enemy?

The image of an enemy, insidious, implacable and merciless, and at the same time (a curtsey towards their own heroism) cowardly and unable to achieve anything alone (this is how the failures and losses of the first Karabakh war were explained), became one of the supporting elements of the constructed identity, which had to be re-realized after the collapse of the USSR and the collapse of the old ideals. The people of Azerbaijan had to remember both their roots and their enemies.

But right now an important question is being resolved – will the politics of memory change? Will Armenians become a little more human in the eyes of Azerbaijanis or will they remain simply defeated enemies? Will new guidelines be identified to save children from the need to draw tanks, grief on the faces of mothers and frown from the suffixes “an” and “yan” (typical endings of Armenian surnames)?

This is how I remember one of the Russian language lessons in 1993. Our beloved teacher mentioned these “bad” suffixes, and we had no doubt that he was completely right.

Of course, the aforementioned Trophy Park does not seem to leave any illusions about the prospects for changes in the mainstream discourse. Other measures taken by one of the main players in this field – the Ministry of Education – say that the authorities are not ready to let go of this source of population consolidation.

The subject “History of Karabakh”, which was studied by schoolchildren in the seventh grade, will be taught in the 9th grade from next year as “The history of victory in Karabakh”.

According to Minister Emin Amrullayev, students and citizens (through children, parents learn about history) will learn about the reasons for the loss of land, long negotiation process, and the victory over the invaders.

Choosing between the momentary benefit from the national unity and the interest in establishing a lasting peace, which in the conditions of total propaganda and revanchist sentiments in Armenia is seen as something unrealistic, the authorities clearly do not even doubt.

But not everything is as simple. After all, it is impossible to simply take and declare to the people that from now on it is possible to peacefully coexist. After many years of propaganda, which was accompanied by the suppression and oblivion of entire layers of history, an abyss formed where people’s memories were buried. They could be in demand if it were the political will and the readiness to build a lasting peace on trust, not hatred.

However, observing the statements and actions of the leaders, it can be seen with the naked eye that they contribute to the widening of the abyss. The traumatic experience of defeat is replaced by a winner’s complex, and any criticism and remarks that, in fact, the sides have simply changed places, are swept aside by the “common sense” of the nationalist discourse.

Symmetrical memories, the opportunity to be heard from both sides, and conversations not only about heroic pages in the struggle with each other could help to overcome the traumatic experience. Until there is a joint catharsis, only a separate story is possible, its own “real” truth.

At the same time, Azerbaijanis will be annoyed by the name of the symbolic monument “We are our mountains” in Khankendi (Stepanakert). Although the word “our” itself could serve as a unifying guideline.

Sociologists and historians speak of the notorious memory of three generations. It is preserved thanks to the existing social framework (social and economic structure, the consequences of war, etc.). With their inevitable change, this memory dissolves and is gradually replaced.

The current rhetoric оn both sides of the barricades, the active participation of both the authorities and various social groups in its maintenance creates all the conditions so that the existing negative memory, which alone is allowed to be present in the public field, will pass on to the next three generations.

These generations will no longer remember either Sayat Nova, or Alexander Shirvanzade, or Arno Babajanyan, or Karen Hovhannisyan, who played the hairdresser Ashot in the famous Azerbaijani film. They will know only strictly prescribed and precisely known “facts”.

Among lovers of conspiracy, the so-called “Lyote plan” is known, associated with the name of the commander of the French troops in Morocco. A beautiful legend says that an elderly general, languishing under the sun, ordered the road to be planted with trees that would give shade. And to the remark that the trees will grow only after 50 years, he cut off that that is why the work needs to start right now.

This is how the “persistent and consistent subversive work of the West”, also known as the propaganda of democratic values, is explained to this day.

But this is exactly what is needed by all those sensible forces that are interested in restoring a lasting peace and preventing another bloody massacre. Enough fighting – start talking.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union