Azerbaijani officer’s account of the second Karabakh war

“I got to the front on the night of the same day when the Second Karabakh war began. Although at that time I still did not believe that it had begun. I thought it was another muscle flexing of the warring parties. In the dark, I familiarized myself with the position, the deployment of the Armenian troops and their guns, still hoping that tomorrow morning this whole performance would end and we would all go home. I fell asleep in the open air on bare ground, and in the morning I woke up from the roar of an exploded shell – no longer able to full myself”.

Agil Hajiyev is 44 years old. The year before, he lost his wife and son in a car accident, and now lives with his school aged daughter, works as a planner for an oil company in Baku, and is fond of literature. Many years ago, under the impression of the army service on the front line and communication with internally displaced persons, Agil wrote the novel “He was from Khojaly”, in which he tried to describe the cruelty and senselessness of war and revenge. Now he is thinking of writing another novel – about the second Karabakh war.

“I was called up as a reserve officer. Being the only family member for my daughter, I would not volunteer. But I was not going to “mow” from the call.

There, at the front, I really missed cleanliness and comfort. But, oddly enough, I didn’t miss anyone in particular. Or I missed everyone and everything connected with a peaceful life at once. I was thinking about traveling to calm places where there is no danger of running into mines or getting under fire. I was thinking about driving aimlessly and taking myself wherever eyes look. It turns out that it is a great happiness when you are not being shot at, and there is no need to be ready for defense or offensive all the time.

The first time at the front is very scary. Over time you get used to it, but you still don’t want and don’t intend to die. It is especially scary when you hear the whistle of a projectile flying in your direction. You cuddle to the bottom of the trench and pray to Allah that this shell does not hit you. It was then that I learned to pray. Before that, I did not know how to ask someone for something, including God.

But besides the fear of death, there is also the fear of being crippled or being captured. And, probably, all these fears are equal in strength. But in the end, I got out of fire, out of the fiercest battles without a single scratch.

After returning from the front, my friends and brother were the first to meet me, and my daughter was waiting for me at home. She is shy by nature and does not know how to show her feelings. But that day, when she saw me at the door, she lit up with joy and rushed to hug me tight. This was the first time I truly felt her love. And for the sake of this moment alone, I am ready to win another war.

During the first days after returning, all the sensations were kind of vague, vague, like that of a drunk. Relatives and friends came to visit, congratulated me, praised me. And I myself did not feel much joy, because I really missed my wife and son. And, probably, precisely because of their death, the war did not inflict any mental or psychological trauma on me. On the contrary, the war, some might say, cured me. In general, after that tragedy, several very strange accidents and coincidences happened in my life, which seemed to make me understand that everything that happens is under the control of the Almighty. And the war was the last of these signs.

At the front, I seriously thought about what would happen to my daughter, who had already lost her mother and brother, if I, too, were gone. And I realized that I have something to live for. Don’t just exist in a state of depression, but live a normal life, be successful and provide my daughter with a good future. Apparently, the Lord sent me to the war purposefully, so that I would wake up.

Also, returning from the front, I learned that our company had undergone a reorganization and reduction, and I was transferred to a new position. Now I am very busy, on weekdays I have almost no free time, and in my case, this is very useful. The only pity is that due to constant workload I cannot devote time to a new novel, which has already begun to write.

I have always understood that Armenians cannot be completely bad, just like Azerbaijanis cannot be good. That it is impossible to perceive and present it in such a form. And I adhered to this principle when I wrote the novel “He was from Khojaly”. But it’s one thing to talk about it while sitting at your desk at home, and quite another to think and act on the battlefield. A moment’s confusion can cost lives, and not only yours, but a dozen of others.

Of course, every person who fought on both sides was a member of someone’s family, someone was waiting for them at home, and someone was praying for them. But the moment we took up arms, everything else lost its meaning. If you do not shoot first – you will be killed. No, it was not difficult to shoot at an armed enemy. It was difficult and painful to do something else, and I could not get used to it: every time, entering a settlement, we walked around the house, left by its inhabitants in a hurry. And in these houses, the sight of children’s clothes, shoes or a stroller lying on the floor pierced my soul times and times again. You look at all this and you realize that you have robbed an innocent child of his calm and joyful life.

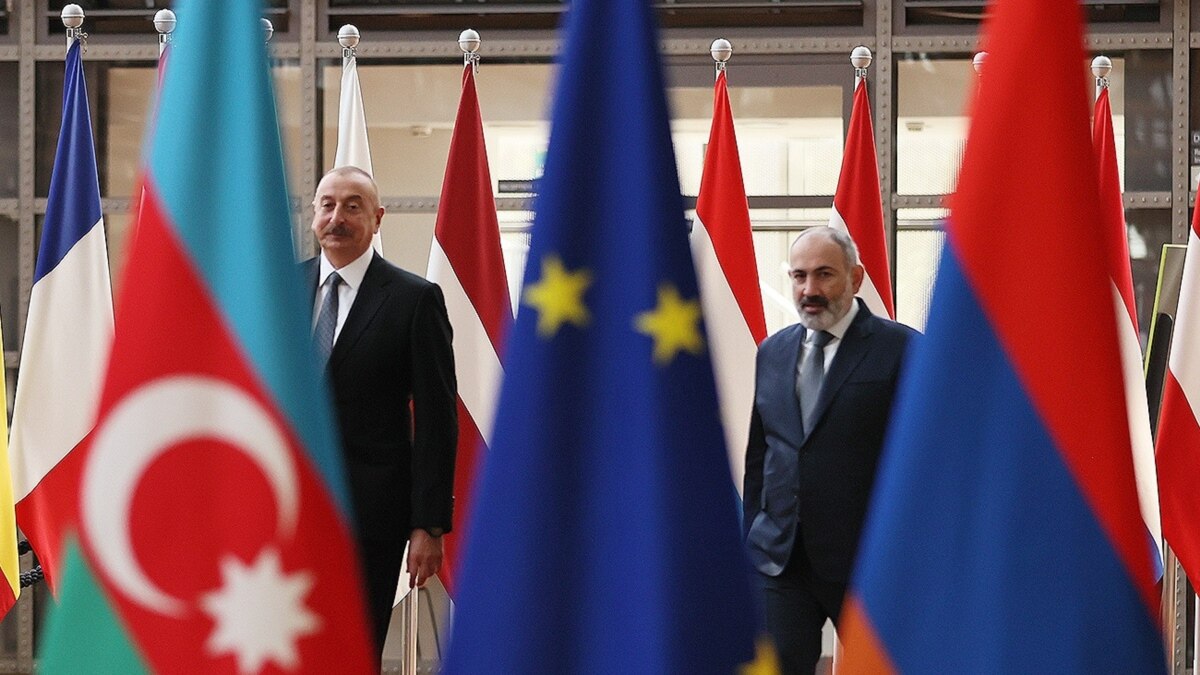

To be honest, I do not think that there will be real peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan. This has gone too far. But relative peace is possible and even necessary for both sides. Our two peoples live at the crossroads of the interests of many major powers. And these powers easily quarrel us when they need it. Only when we both realize and acknowledge this fact can we achieve a more sustainable world, protected from external influences. Politicians and ordinary people should act in this direction”.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union