The future of Azerbaijani architecture is already here

Stairway lovers: Baku’s urban sciences team

The village of Baylovo, though technically a part of Baku, dveloped on the slope of a hill which residents call Mount Baylovo. Because of the slopes, the streets run horizontally and vertically, and most of the vertical ones are actually stairs that takes you from one level to another.

And walking along these stairs is of course difficult, especially during Baku’s fierce summers, where every step becomes harder and harder.

But Leyla likes stairs. Probably because she is a young architect from the ‘Pille’ (meaning a step in Azerbaijani) workshop-studio. These architects have a different outlook on the world. Leyla, for example, calls stairs ‘transitions’ and regrets that people don’t give them enough attention.

But Leyla likes stairs. Probably because she is a young architect from the ‘Pille’ (meaning a step in Azerbaijani) workshop-studio. These architects have a different outlook on the world. Leyla, for example, calls stairs ‘transitions’ and regrets that people don’t give them enough attention.

“Moving up a stairway, we always notice its details, even if only on the edge of ours [our peripheral vision]. Even if there are many of them, and if sometimes we can’t tell one from the other. In my opinion, it would be interesting to pay a lot of attention to these details – to focus on something interesting, to think about it or just enjoy it.”

Moreover, these shabby stairways could be made to come alive and decorated so that walking on them would remind one less of the punishment [of walking on them]. And that’s the kind of work that participants of the ‘Urban olum’international architecture festival, organized by the Pille workshop-studio, will be focussing on. The festival started today in the village of Baylovo and will last two weeks.

Who are they?

Pille is not an architecture office in the traditional sense, but rather an association of like-minded people. Currently, it has eight architects: Muslim Imranli, Leyla Musayeva, Dilara Orujzade, Sabina Abbasova, Farid Abdulov, Aygun Budagh, Subhan Manafzade and Chichek Bayromova. Nezaket Azimli is, in her own way, the manager of the studio, however she is not an architect but is interested in modern urban concepts and intends to study in this field.

Urban studies is the science of the development of cities and how different city systems interact with each other and with people. One of the Pille team’s main goals is to emerge from the field of architecture and do more work that is connected with urban planning, and to convince whomever they can that streets and homes are practically live-beings that play a much larger role in our lives than it may seem.

Four of the members of Pille studied together in the Azerbaijani University of Architecture and Construction. However, according to them, it would be difficult to call what they received there an education.

“In our university, with the exception of a few subjects (for example, restoration or art history), students were (and continue to be) taught things that barely work or are incredibly out-dated. We received our main skills at on-site trainings, abroad, from books or at trainings of foreign specialists.”

However, having made one another’s acquaintance in university, these four members of Pille became practically one family. And quite literally, in some cases: two of them, Farid and Sabina, recently married. It was a few years before the entire team could celebrate the wedding. For after receiving their bachelor’s degrees, several of the members went abroad for their masters, and met again two years later. Somehow, talking on a bus late at night coming back from an out of town excursion, they came up with the idea of creating a workshop.

“We decided to call ourselves Pille, because on one hand a step is an element of architecture and on the other hand, it is a symbol of the constant movement upwards. But in this case, the idea wasn’t just the worn-out phrase of ‘stairwa to success’. Sometimes, the simple act of moving upward is more important than ending up at the top.”

What do they do?

The first project Pille implemented was called ‘The history of shaping Baku’ and was realized ‘for the soul’. During the project, they decided to fill in the gaps in their knowledge about the history of the city, which had interested them from their time as students.

Another annoying circumstance was the fact that there was a real lack of ‘accomplices’. That’s how they came up with the idea of holding workshops for the youth. The Pille team started hosting lectures about urban sciences, and the more capable of those in attendance eventually ended up joining the team.

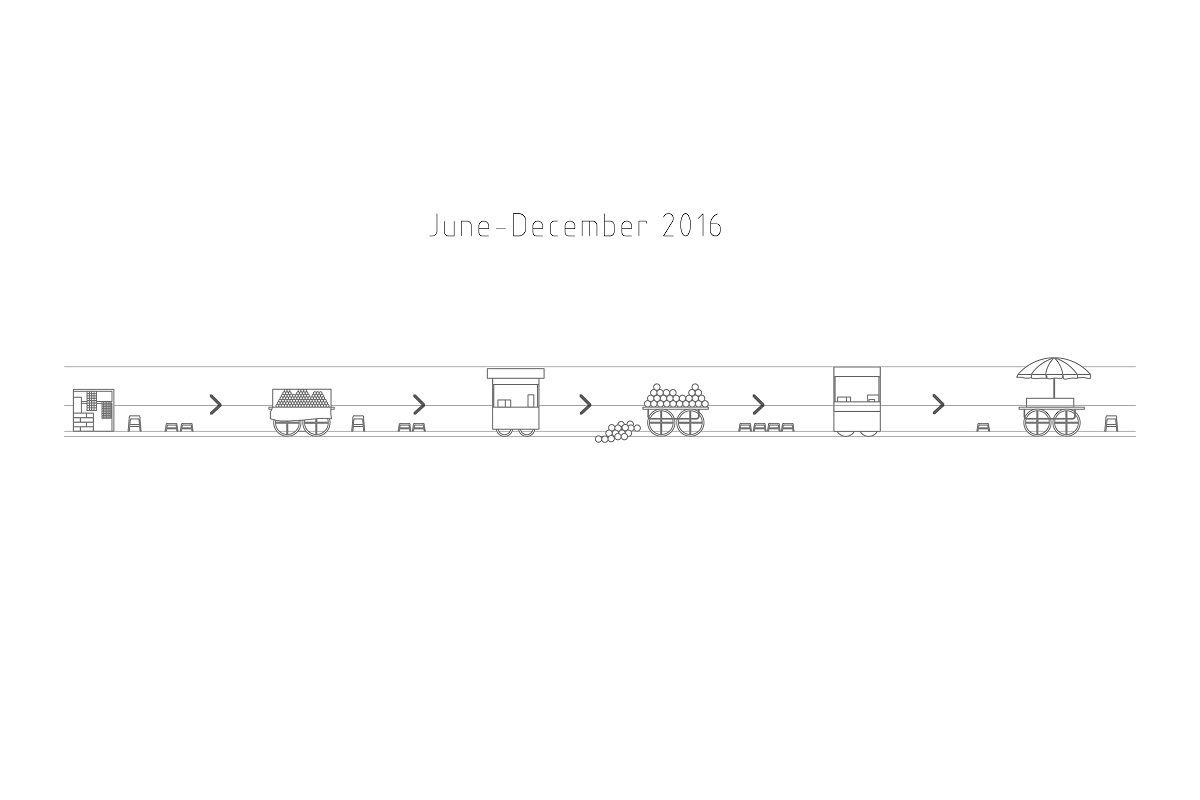

A substantial result of Pille’s work can be found in a project that created a folding, multifunctional carriage for selling food on the street. It was developed with students during a workshop called ‘Urban Furniture Workshop’.

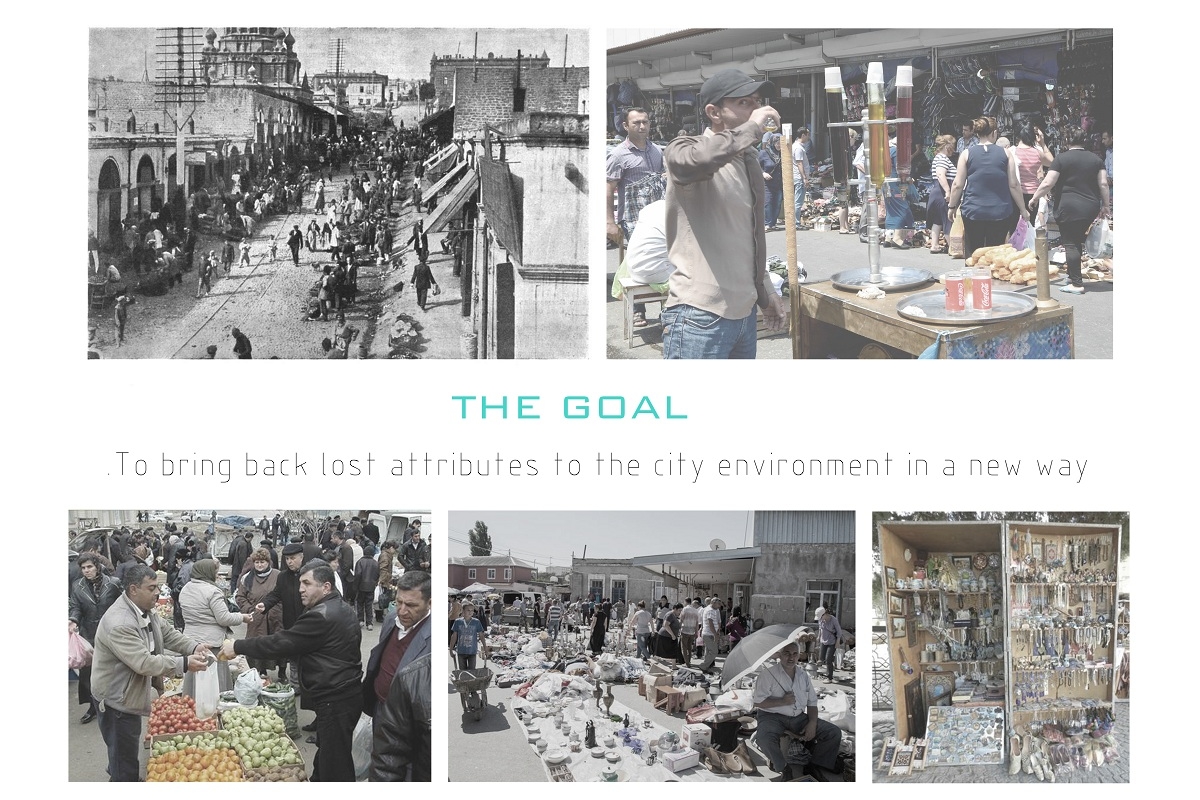

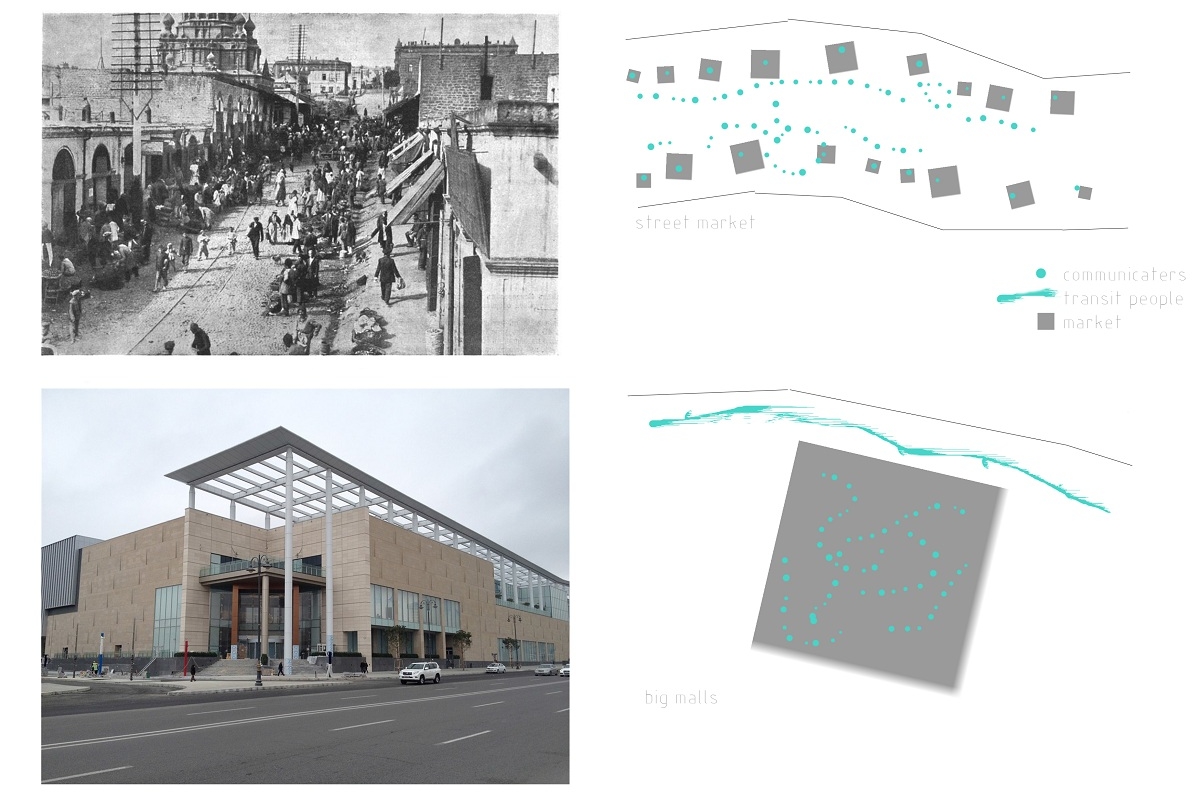

The presentation figuratively demonstrates that the streets of modern Baku are losing their traditional form and in the meanwhile fulfilling only a transitory function. The aim of the project was to ‘pull’ streets into social life, and return to them their authenticity and to support small businesses.

“Up until recently, it was forbidden in the center of Bakuto sell food on the street from carts. But this small detail really brings the city alive, adds some charm to it and the residents really like it, as do the tourists. Think about the walnut fryers on the streets of Istanbul.”

Several months after the presentation of the project, the ban on ‘mobile food stands’ was lifted in Baku and though Pille does not consider this to be to their credit, they cannot deny themselves the pleasure of seeing at least something of an interconnection.

Pille and Baku

Leyla:

I can’t say that I love some particular part of the city more than the other ones. It’s more like: I like their co-existence, their coming together as one. The ability to go from one atmosphere of one part of the city to another is very interesting.

Chichek:

I lived for many years in Tatarstan and I returned to Baku only a year ago. It was difficult to assimilate, and sometimes I wanted to block myself off from everyone and be with myself in the calm and quiet. A good place for that was the Old Town, because it is separate despite being in the center of town. There is a different life there, another kind of atmosphere. There you can feel the spirit of history, which you almost don’t have at all in the rest of big Baku. In the Old Town, I had three favorite sports, one was for thinking about my personal life, another was to think through problems and the third was for getting inspiration and coming up with plans.

Muslim:

The places closest to my heart are far from the center, in the village of Sabunchi, where I grew up. There, across from the entrance to the hospital is a library. The building in which it is housed was earlier a part of an Orthodox church which was demolished by the Soviet in 1934. Despite its small size and rather unattractive look, inside there is a calming atmosphere. And it’s namely there in the 7th grade that a dusty, Soviet book fell into my hand: «Architecture». This was my first experience with the world of architecture.

Aygun:

I moved to Baku when I was five years old, and since that time I’ve been living on the outskirts of town by the so-called ‘8th bazaar’. This is a legendary place, you could say. Many don’tlike it, but it always seemed to me a bright, colorful and original place. It has its own charm, and I would like for it to be maintained, and for it not to ‘fade out’. Unfortunately, recently it seems that is what has been happening.

Nezaket:

I really like the district ‘Zavokzalnoy’. When you go up from the train station, you are surrounded by old courtyards which have totally retained their coloring and atmosphere. There is also the Church of the Holy Mother of God. I especially like to walk in this area in spring, when trees are blooming in every courtyard.

Farid:

Honestly, I don’t like Baku. I like more compact cities, with a proportional ratio of green to sand and stone. For example, I was in Malta, and in just a few days I stopped liking it, because there is practically no greenery there, and too much sand. But, for example, Izmir I love, though it is also small, but they control the size of everything there, and there aren’t many towering buildings. The city itself is very varied, colorful and has an interesting geographic location. In just half an hour you can get to the forest, mountains or agricultural locations. Baku is more desert-like. Of course, there is something romantic and poetic about that, but I’m not crazy about Baku.

Sabina

I really like ‘sincere’ Baku with its low-rise neighborhoods which are slowly disappearing. I understand that this is inevitable, that the population is growing, and that to expand the territory would mean to undermine the economy and that the solution is to increase the number of high-rises and take down the older low-rises. That would be OK if they built these high-rises with care and competently, taking into account social spaces.

I really like the district of Darnagul, where I lived for 15 years. It’s self-organized, atmospheric and safe. I like the central street Istiqlaliyyet, which is very pleasant, graceful, pretty but not pompous. I now live two steps away from it, which I am very happy about and I try to walk about the street when I can.

Recently, Pille got themselves headquarters, and now youth who are interested in urban sciences can go there and have the kinds of conversations that laymen would find difficult to understand. It’s not accidental, probably, that the workshop ‘settled’ not far from a place that the people call ’40-steps’ – another long set of stairs.

Standing on the balcony, one can discuss the plusses and minuses of experimental Soviet structures in comparison to the high-rises that stand across the street. In the evenings, one can turn off the lights and turn on the decorative lighting, which wind around the sofas. And in one’s free time, one can go walk in some god-forsaken part of the city to ‘explore’, in order to stumble upon something along the lines of a tiny BBQ joint with great food, an usual building or original graffiti on a wall. In recent times, such walkabouts have become a profession: having passed professional guide courses, Farid, Muslim and Leyla have begun to lead excursions through Baku, Absheron and other regions of the country.

“We try to show and tell tourists something non-standard [unusual or surprising], which you can’t read about in guidebooks. For example, if you take someone inside an old Baku Italian-courtyard, it can tell tourists much more about the life of the city than its center can. And when you speak about some main attraction, such as the Maiden Tower, you can always find an interesting approach to speak about it, instead of simply presenting the facts. Tourists find this much more interesting, as do we.”