How the Earth is safeguarded in Abastumani

There is a big, white building with an oval dome on the Kanobili Mountain, at the altitude of 1,700m. above the sea level, some 5kilometersaway from Abastumani settlement (Samtskhe-Javakheti region, southeastern Georgia).

Every night, the dome door opens and a huge device, that is a bit rusty here and there, with a glass eye cast far away, towards the stars, pops up from the slot.

That’s Abastumani Astrophysical Observatory. Built in the ‘30s of the 20th century, this unique scientific center is gradually losing its function.

The observatory will turn 85 this year. This historical facility is going to mark its anniversary with rich history and tattered infrastructure.

‘So long! Wish you a cloudless sky!’–with these words Shota Inasaridze’s wife has been seeing her husband off to work every day, or to be more precise, every night, for 42 years already.

Shota dresses up warmly, tightly buttons up his coat, not forgetting about putting on his scarf and gloves, and walks down the snowy road to his work.

“It is 7 degrees below zero today, whileI will have to spend the whole night in the open air,” he says.

Shota is a senior research fellow at Abastumani Astrophysical Observatory. His working day starts at 8p.m. and finishes at the daybreak, at about 5-6 a.m.

At present, he studies one of the dangerous asteroids that poses risk to Earth.

“You should look through the eyepiece every minute so that the object won’t leave the field. Otherwise, nothing will come of it,” Shota explained. He agreed to showus around Abastumani Observatory.

A weight clock, past-century science periodicals and the only operating telescope

The observatory area stretches for about 33hectares. In olden times, it looked likea separate town, with thousands of scientific, technical and residential facilities, where people worked, conducted experiments and lived. Abastumani observatory was the first mountain observatory in the Soviet Union.

Those buildings are still there, but most of them are closed. There are rusty locks on the doors, smashed windows, creaky doors, paint peeled-off walls and crumbled plaster.

We entered the central building with an oval dome on top of it.

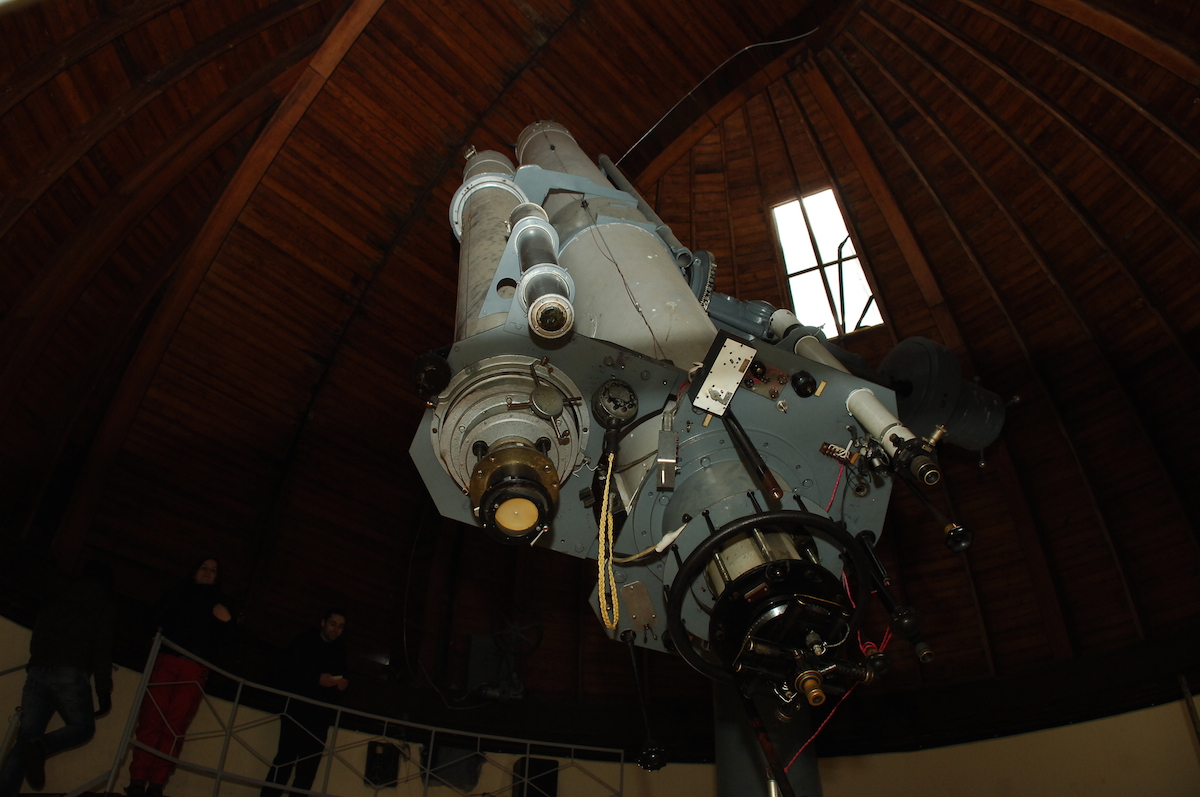

There are old-time posters with Russian-Georgian inscription at each room entrance. ’70-cm. Meniscus Telescope’- one of the posters reads. Georgian font of the inscription is so old that it resembles the one that could be found in the past century’s magazines

How did Abastumani’ history begin

Foundation of the observatory is attributed to Giorgi Romanov (1871-1899), the son of the Russian Emperor, Alexander III.

Giorgi Romanov, who suffered tuberculosis, settled down in Abastumani in the 90s of the 19th century. He and Sergei von Glasenapp, his friend and astronomer, who was visiting him in Abastumani, used to observe the starts through a 9,5-inch refractor.

Later, when Glasenapp published his works, it turned out that despite the poor-quality equipment, the data he produced were the best at that time, which was largely conditioned by Abastumani’s clear and specific climate.

Glasenapp’s observations laid foundation to setting up the first observatory in Abastumani.

“Abastumani offered such favorable conditions for observation, that I set my whole mind on work. I spent nights making observations and was calculating the orbital elements of double stars in the daytime. I was preoccupied with that work and the year passed by quickly. Then I returned to St. Petersburg. I deeply regretted leaving Abastumani, where an astronomer can work so efficiently,” wrote Glasenapp, who at that time observed 610 stars.

Later, on February 8, 1932, Georgian SSR State Committee Council issued a resolution on establishment of Abastumani Astrophysical Observatory.

“The European astronomers are often puzzled at seeing our control room, wondering how we handle all those buttons, while in the modern control rooms they have been replaced just by a few of them,” said Shota Inasaridze, showing us a huge steel construction with really millions of buttons.

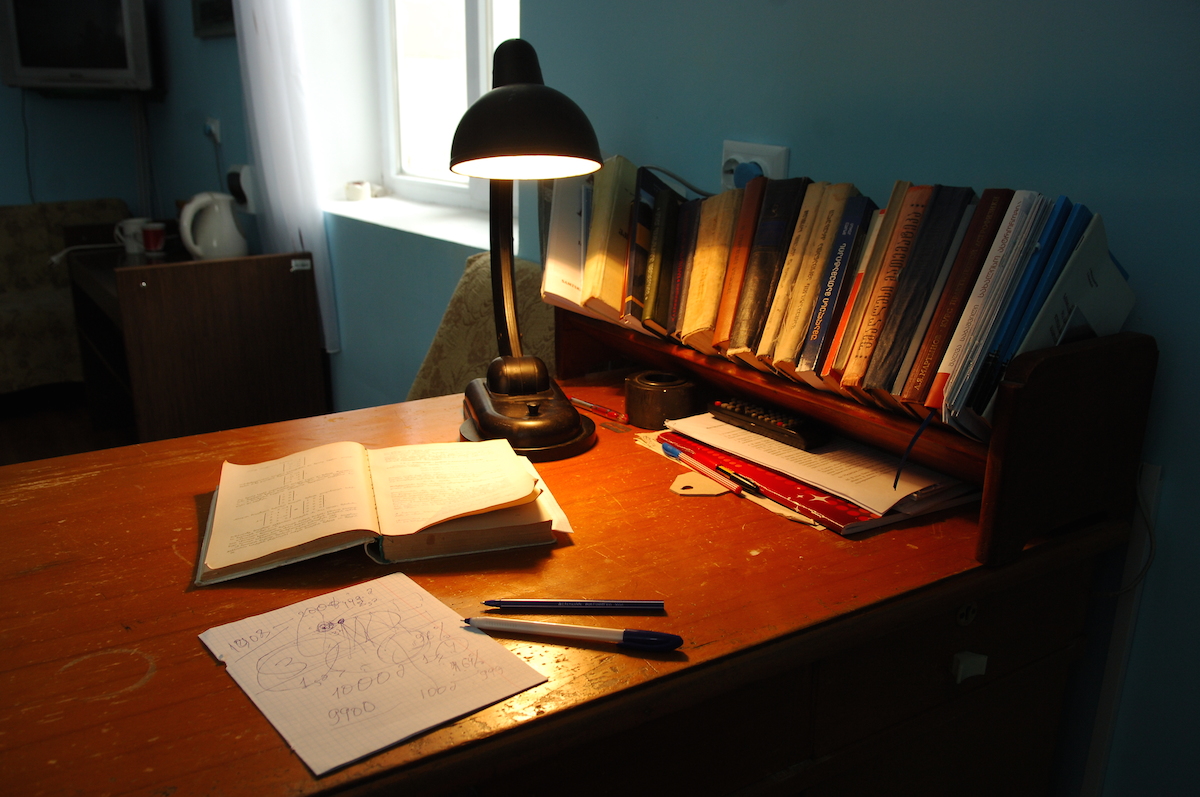

The rooms here are full of old-time chronometers; there is the Moon map, published by the Moscow-based ‘Education’ publishing house in 1979, as well as the Prague publishing house’s 1959 Northern Sky map, hanging on the wall; there are dustyjournals and astronomycalendars scattered around the desks. “St. Petersburg, 1996’, reads one of the journals, yellowed as a result of lying on the desk in the major telescope’ control room. As Shota explained, this journal includes star positions and planetary trajectories: “This is, actually, an astronomer’s guide. We had subscribed to it and received it earlier.Whereas now, we can’t afford science journal subscription.”

Abastumani Observatory is one of those rare facilities that didn’t stop functioning after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 90s. Shota Inasaridze is obviously proud of this fact.

Shota’s office is warmed up with electric heater. The only modern item here is a laptop, on which the researcher processes the data obtained as a result of nigh sky observations. And also, there is an electric kettleto warm oneself up with a cup of hot tea in cold nights.

There is a wooden clock on the opposite wall, that dates back to the ‘60s and that rings every half an hour. This sound makes Shota slightly flinch, he removes his thick-frame glasses, cleans them and skillfully puts them on again, trying to demonstrate through a drawing what is done in the observatory now.

A sudden and solemn ringing of this weight clock hanging on the wall, an old lamp and a yellow shabby wood table further distance us from the cosmic space and put us back to the 19th century, tothe times, when Emperor Alexander III’s son, Giorgi, was visiting Abastumani.

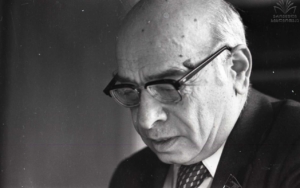

Evgeny Kharadze, the first director

In 1990, the observatory was named after its first director, Georgian scholar, Evgeny Kharadze. However, later, in 2007, when the observatory was transferred to Tbilisi Ilia State University, Kharadze’s name disappeared from its title and it was renamed into Abastumani Astrophysical Observatory again.

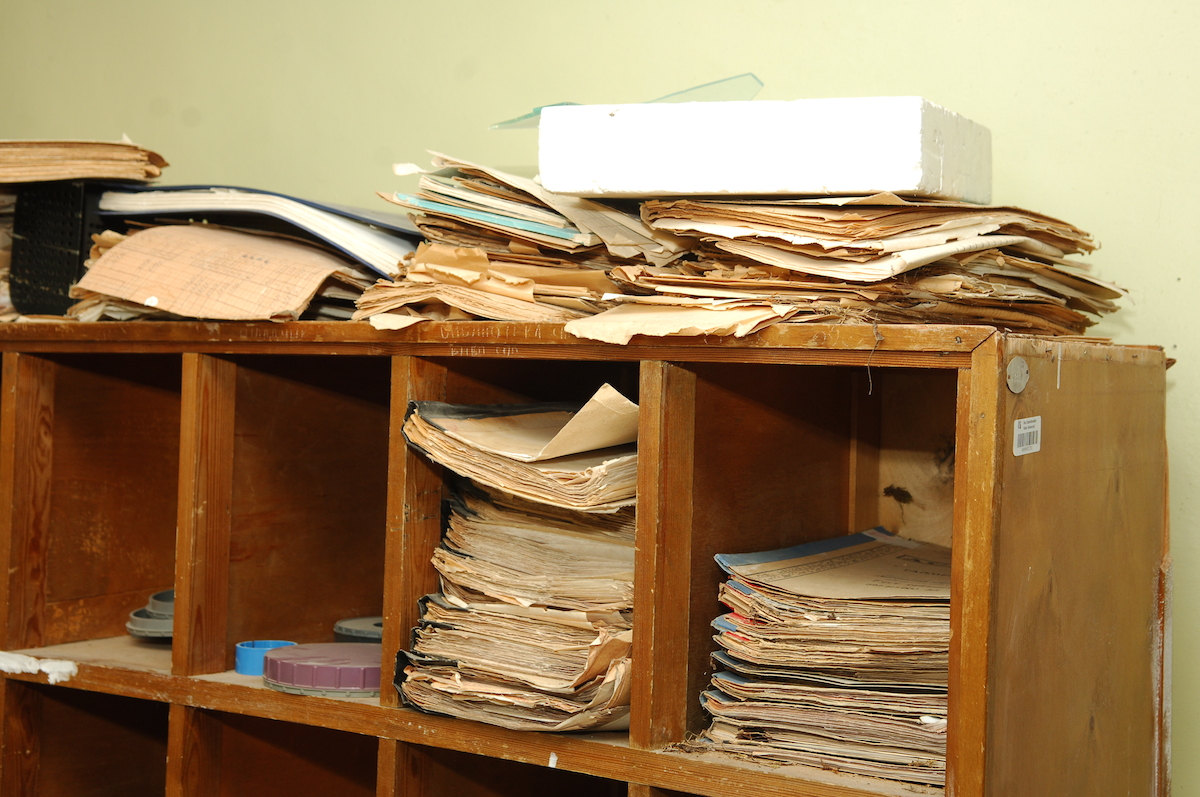

Evgeny Kharadze’s trace could be found everywhere in the observatory. His office room, packed with his personal belongings, is one of the major landmarks in the observatory museum.

Photo/video: Sergey Fidanyan

Only 4 out of 10 observatory telescopes are operating nowadays. Observations are made with a 75-cm. telescope, installed here back in 1956:

“All of us who want to make observations are hung up on this telescope,” Shota explained, sharing with us a story of this steel construction.

“It’s a historical telescope. In 1970, Roland Kiladze developed the distant artificial satellites observation technique using this telescope. This method is still widely applied nowadays for the artificial satellites observations,” said the researcher.

There is also a bigger, 125-cm. telescope in the observatory, but it has been broken for 6 years already. In Shota’s words, EUR220,000 are required to repair it.

“Our Czech colleagues are ready to repair it gratuitously, but the government has failed to raise necessary funds for procurement of spare parts.Neither the government, nor Ilia University, have those funds,” said Shota.

“We sent a letter to the Georgian Education and Science Ministry, explaining that the observatory equipment was outdated and required modernization. We requested either to repair a 125-cm. telescope or to buy a new, modern, robotic one. We also garnered the foreign colleagues’ support. So, we hope, we will get the result,’ Maia Todua, Ilia State University Professor, confirmed in a phone interview.

Everything in the building, where the telescope is installed, is covered with dust. On the one side, there are bowls on the floor for collecting the water that leaks from the roof. And, on the other side, there are some devices wrapped up in cellophane. It is at once apparent than they haven’t been switched on for quite long. It’s so cold in the room that staying there even for 5 minutes will make one clam up.

“Sometimes we have to work with telescope all night long in 17 degrees below zero. Besides, we don’t have any special clothing for such extreme cold conditions. Once, my feet were frostbitten,” said Shota.

Dangerous asteroids

“We are the members of the global network and we’ve been observing near-Earth asteroids since 2012. All world observatories have been engaged in asteroid observation as part of the UN project, since 1992,” Shota told us.

The researcher also familiarized us with his discoveries. It turned out that Apophis, a near-Earth asteroid that was predictedto hit the Earth in 2029, started to retrograde:

“On February 13-15, 2014, we saw that it made a loop, turned back and moves away. It didn’t approach us, but rather retrograded. We are guaranteed that it won’t hit the Earth for 50 years. We sent the materials to Paris and it was confirmed that Apophis no longer posed a threat.”

Though, there are still some dangerous celestial objects:

“There are many near-Earth asteroids, the movement trajectory of which needs to be known. Now, we observe the asteroids that exceed 1 kilometer in diameter. 96% of them have been already recorded. You may wonder, what can we do?!The point is that we know about possible collision 3 months in advance. If it is established that it is going to hit the Earth, an unmanned spacecraft should be sent that will either land on it or use a gravity ‘towline’ to tug an asteroid from a collision. We have to avert it. In other words, we are safeguarding the Earth.”

Abastumanistars don’t flicker

Климат того места, где намечено строительство обсерватории, изучается загодя. Необходимо, чтобы он соответствовал нескольким важным условиям – максимальное в году количество безоблачных ночей; удаленность от больших городов, поскольку выбросы и уличное освещение «портят» небо; спокойная безветренная атмосфера, прозрачность неба и, что главное – звезды не должны мерцать. Абастумани отвечает всем этим условиям. Например, тбилисское небо «загажено» выбросами и свет, посылаемый звездами, доходит до нас мерцающим.

Shota Inasaridze spent 252 nights safeguarding the Earth last year:

“There is no chance that I would stay at home in a clear night. There are some things that we, the astronomers, lack to a certain extent. A normal person will go to bed at night, whereas we get up and leave. You should love it, otherwise you won’t be able to do it, you won’t stand it.”

There is only one discovery so far, that is associated with Shota’s name. It is dated back to his youth, to 1980, when he discovered a stella supernova, that now bears his name. Shota says, there is still much to be done.

Andranik

Our sightseeing tour continued in the optics and equipment lab. Having opened anewly painted red, metal door, we found ourselves in the last century again.

Andranik Ambartsumyan has been working in the lab since 1965. His duty is to repair telescope parts, as well as upgrade and manufacture its filters and mirrors. The researchers’ work is impossible without him.

Andranik is proud to work in the Alexander Mayer’s office. Mayer was the first person to head the optics and precision mechanics lab.

On entering the opticist-mechanic’s room we immediately discovered a black-and-white corner-a Soviet-time phone, telescope models, temperature gauge, tools and thousandsof other small ware-everything that is necessary for the telescope repair. ARussian-language poster on the wall reports that ‘Velekolepnaya Semerka’ (The Magnificent Seven) would be screened in the cinema house on September 27.

“This photo was taken during the 1980 solar eclips expedition, in the Siberia,” said Andranik, showing us the photo. He participated in that expedition in the capacity of a telescope opticist-mechanic.

He endured the Siberian climate, whereas now, he warmsup the room with a wood heater so as to withstand Abastumani chilly nights. He doesn’t have special clothing either. The stove is hardly enough, so he has to work in coat. When he has a break, he waters the flowers that are lined up on the window-sills. A blossoming Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera) is the only colorful thing in the mechanic’s office.

“The observatory is my home and my family. I’ve spent here all my life,” says Andranik. He sits down to the magnifying lens and starts working. A fixed part of one of the operable telescopes, which broke down a couple of days ago,is lying right there. It will be attachedto the telescope in two days and Shota will continue his work.

Who studies astronomy in Georgia?

“For example, my students prefer to work in bank for GEL800-1,000, rather than here, in the observatory, where the salaries start at GEL300. I have the highest salary amounting to GEL900,” Shota tells us.

Apart from the observatory, he also delivers lectures at Samtskhe-Javakheti State University:

“Fewer young people show interest in the astronomy nowadays. If things go on like this, the observatory will probably cease to exist in a decade.”

Samtskhe-Javakheti University is one of few higher education institutions that offers Master’s degree and PhD programs in Astronomy. Although there are students, but most of them don’t take astronomy seriously:

“Astronomy has been declared a priority trend and the government provides funding for students studying it. Students often choose it for that very reason. They take a course in Economics, undergo Master’s Degree program in Astronomy and then take a job in bank. Why are you wasting state funds if have no interest in this field? Though, I understand the students, too. They have no other way out.”

The researcher believes that main problem still lies in the government’s approach. In his opinion, the government doesn’t grasp the importance of the observatory for the country. There is little promotion of the field and that has an influence on the youth.

“Astronomy isn’t taught either at schools or in the majority of the universities. If you have a look at our observatory, you’ll understand the government’s attitude to it. And that certainly has an influence on the youth.”

“I have had a chance to obtain the Master’s Degree and, at the same time, to take a free course in the major that has great future prospects,” says Tiko Kuljanishvili, a graduate of 2014 Matser’s Degree program at Samtskhe-Javakheti State University.

Most of her mates in a 10-student group missed the lectures due to their work.

She herself works in the nongovernmental sector and she hasn’t tries the astronomer’s job yet.

“I’ve been thinking about taking a job at the observatory, but do you know, how poor the conditions there are? On the other hand, it would be so interesting to observe the stars.

Astronomy courses are available only in 3 out of 194 higher education institutions in Georgia – in Ilia State University (ISU), Tbilisi State University (TSU) and Samtskhe-Javakheti State University (SJSU). At the same time, Ilia University is the only institution that offers Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programs in Physics and Astronomy, whereas PhD program in the aforesaid fields is available in all 3 universities. There are currently 15 PhD students in Ilia University, 2 – in TSU and 7 – in SJSU.

Astronomy was also removed from the mandatory subjects’ lists in Georgian secondary school. As we were told in the Education Ministry, under the 2011-2016 national curriculum, astronomy is an optional subject and it is taught in the 10th grade only if required by the majority of students: “Though, it can’t be said that this subject isn’t taught at all. Physics and Geography, that are taught in lower grades, also cover Astronomy to some extent.”

There is no information on the precise number of students from 2,085 schools throughout Georgia, who have chosen astronomy. The Education Ministry says, this issue is subject to inquiry.

Amateur Astronomers

Temo Kuchadze is majoring in history, but he has been indulged in astronomy in recent years. He refers to himself as an amateur astronomer.

He was 15, when his uncle presented him the children’s ‘Cosmos’ encyclopedia and they started observing the sky through an amateur telescope. Since that time, he has been engaged in this field.

In 2014, he set up the astronomy fan club on Facebook, which currently unites 8,748 members, including 1,000 active ones:

“There are both, amateurs and professionals, among the club members. We organize group discussions, raise questions and share interesting materials. The group serves to promote the astronomy.”

The group members organize practical outings with amateur telescopes from time to time.

They held a mass campaign in Vake Park, in Tbilisi, last year. “We brought several telescopes and people could look though it absolutely free of charge. More than 300 people attended the event. There is public interest, but it’s still at the amateur level. No one in Georgia dares to choose Astronomy as a major- it’s not promising.”

Temo’s Astronomy fan club isn’t the only one on Facebook. There are several similar amateur groups on social media.

Rehabilitation and astro-tourism

How to re-kindle lost interest in the cosmos?

All astronomers, be it professionals or amateurs, have a single answer to this question – it could be achieved through government’s facilitation and promotion, which implies several trends and mere rehabilitation of the observatory is hardly enough.

In 2017, it is planned to carry out rehabilitation of the observatory as part of the Regional Development Project-3.

The project will be executed by the Municipal Development Fund.

The following works will be performed in the observatory in accordance with the tender documentation: rehabilitation of the big telescope facility; improvement of the area adjacent to the main design building, as well as the settlement’scentral territory; rehabilitation of the cableway; arrangement of parking lot and communal WCs. According the Municipal Development Fund, at this stage there is no detailed information on the amount to be spent on rehabilitation. What is known so far is that the worksshould be launched this year and be completed in February 2018.

This project, which is financed by the Georgian government and the World Bank (WB), doesn’t quite seek to promote scientific researches, but rather aims to facilitate tourism development.

“The project doesn’t provide for telescope modernization, since the WB finances only rehabilitation of infrastructure. Their funding doesn’t cover the science equipment. In this regard, we require the government’s funding,” said Maia Todua, Associate Professor at Ilia State University, Observatory Director.

Astro-tourism is still popular in Abastumani nowadays. There is a guide at the Observatory who shows the visitors around the building. You can also look through a telescope and observe the stars. If you google Abastumani Observatory in English or Russian, you’ll find a lot of tourist blogs that will advise you to travel to Abastumani and will also provide some guidelines.

Shota doesn’t like the new project.

“Tourism is certainly good, but the observatory isn’t a tourism center, is it?!Observatory is a scientific place. How are we supposed to make observations if they arrange terraces and organize disco parties here? They don’t understand that. This project has nothing to do with promotion of science,” he told us.

In his words, bright illumination of the recently rehabilitated Rabati fortress in Akhaltsikhe, as well as increased air routes over Abastumani, already hamper their scientific activity. He believes that if put into effect, the project will further spoil the researchers’ job.

Through implementation of the new project, the government seeks to attract more tourists, which will result in additional incomes to the region.

“If I have had a 3-meter diameter telescope, I would have promoted Georgia worldwide every night, I would have done a lot and that would have brought more renown and money to my country. That’s my dream,” said Shota.

It was getting dark. Shota locked his office, saw us off and went up the crooked stairs to the 75-m telescope building to spend one more cold night standing on guard.

*Nino Narimanishvili, an author of this material, is an employee of the ‘Samkhretis Karibche’ (Southern Gateway) newspaper.