When artists get sick

One hears various rumors about mental asylums: that patients are treated with electroshock therapy, after which even healthy people lose their minds, and that once one gets inside, one almost never returns and so on. Baku Psychiatric Hospital No. 1, known by the name of Mashtagha, is a well known place, and there are a number of different rumors about it.

Mashtaga is a village forty minutes away from the center of Baku. There’s only one bus to get there: No. 172. Along the road one can see the typical landscape of the dacha-towns that surround Baku: stone walls, desert lands, fig trees.

You can’t not see the Mashtaga Psychiatric Hospital as you pass by: the bus stop is near its large gates. Often, people get off here, and for that reason, as soon as the passenger asks the driver to stop, one can often guess the reason for his visit. If they ask the driver to stop ‘near the hospital’, then that means they’ve come to see a patient. Everyone else just says ‘stop near the madhouse’.

At the entrance, policemen ask visitors why they’ve come and who they wish to see. They call the hospital to check. Sometimes they search purses and bags. On the hospital grounds one can find an investigative detention center for suspects whose sanity is in question, and other safety measures that you can find in a similar institution. There are observation cameras everywhere to help with security issues.

The hospital, the largest in the country, takes up a few hectares. It’s easier to go between its buildings by car than by foot. The territory of the hospital might remind one of a Soviet period ‘sanatorium’: asphalt, trees, even artificial ponds.

Mashtaga Psychiatric Hospital opened in 1936. In the beginning, there were three departments that could handle up to 100 people. Now there are 30 departments, amongst which are 6 for women, 12 for men, 4 for tuberculosis patients, a children’s ward, an adolescent ward and an infection ward. There are more than 300 patients, people who have lost all social connections and they have thus fallen into the care of the hospital.

In the clinic there are four modes of detention: open (the patient can move about freely on the territory of the hospital), semi-open (the patient can move about with the supervision of staff), closed (the patient cannot leave the building) and isolated.

Electroshock therapy

Electroshock therapy is not such a long and dangerous procedure as is depicted in some films. It is used to ease a person’s state during a seizure or for Alzheimer’s patients.

The procedure takes about two seconds and can be used only with the consent of the patience. Saida Huseynova, a clinical psychologist, says:

“When I started working in Mashtaga, I asked to be present at an electroshock therapy procedure. As a psychologist, I wanted to see it. I wanted to see both the process of the treatment and its effect.”

As concerns treatment methods in the hospital, both medicinal treatment and psychotherapy are available. The aim of medicinal treatment is to calm the nervous system in order for the patient to be able to receive psychotherapy which is impossible to apply in particularly intense periods of neurosis or psychosis.

How does one end up in the psych ward?

If a person receives a diagnosis, it does not mean that he or she will be forced into a hospital. The head doctor of the psychiatric hospital No.,1 Agahasan Rasulov, says: “In order to force a person into treatment, there are two conditions: either a person is a danger to himself, or to those around them. Not all patients may appear dangerous at first glance. But it has happened before that a patient asked his mother to take him home, and then he burned down the apartment.”

The decision to forcibly place a person in treatment is made by a commission.

How to get out?

Another myth: if you end up in the hospital, it’s forever. However, Agahasan Rasulov says that this is not so.

“Statistics will talk better than I can. Over 2014, we had 10,680 patients signed out. In 2015 we had 2,896. It’s true that not every illness is treatable. That’s about 30% of the patients. But even in the case of chronic illness, there is a possibility of treating its severity. A person that was once a patient of the clinic may eventually be your boss. For a large part of his life he’s a regular citizen, but for some time he may come to the hospital before his symptoms get worse and wait for remission.”

Saida Huseynova says that the chances of rehabilitation depend on the diagnosis. “People that suffer from obsessive compulsive disorders are treated 100% and re-enter society.

“We had a patient who was about thirty years old if I’m not mistaken. He participated at exhibitions, and sometimes played the accordion. His diagnosis was paranoid schizophrenia. But he received treatment in time, and the state of remission lasts much longer. People who suffer from schizophrenia are used to social isolation, but rehabilitation helps them to readjust to society.

“Another patient who has schizophrenia sings at weddings. Many know him. That is to say, despite his illness, he is able to earn money and respect. And when his condition worsens, he comes in for treatment.”

Artists

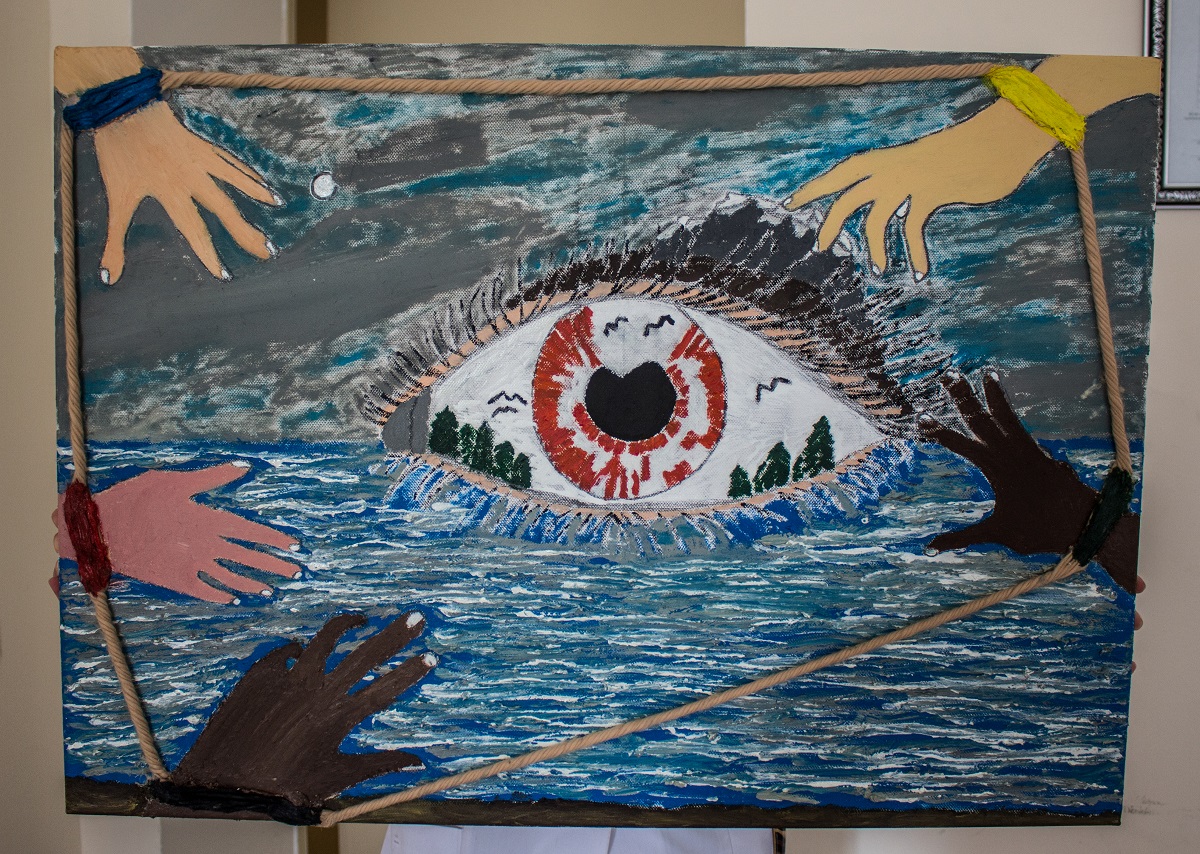

In addition to medicinal and therapeutic treatment, in Mashtaga there is a department of rehabilitation as well. Rehabilitation therapy is needed in order to help the patient reintegrate into society. Patients are asked to create, be it figures made of plasticine or pictures.

Imran

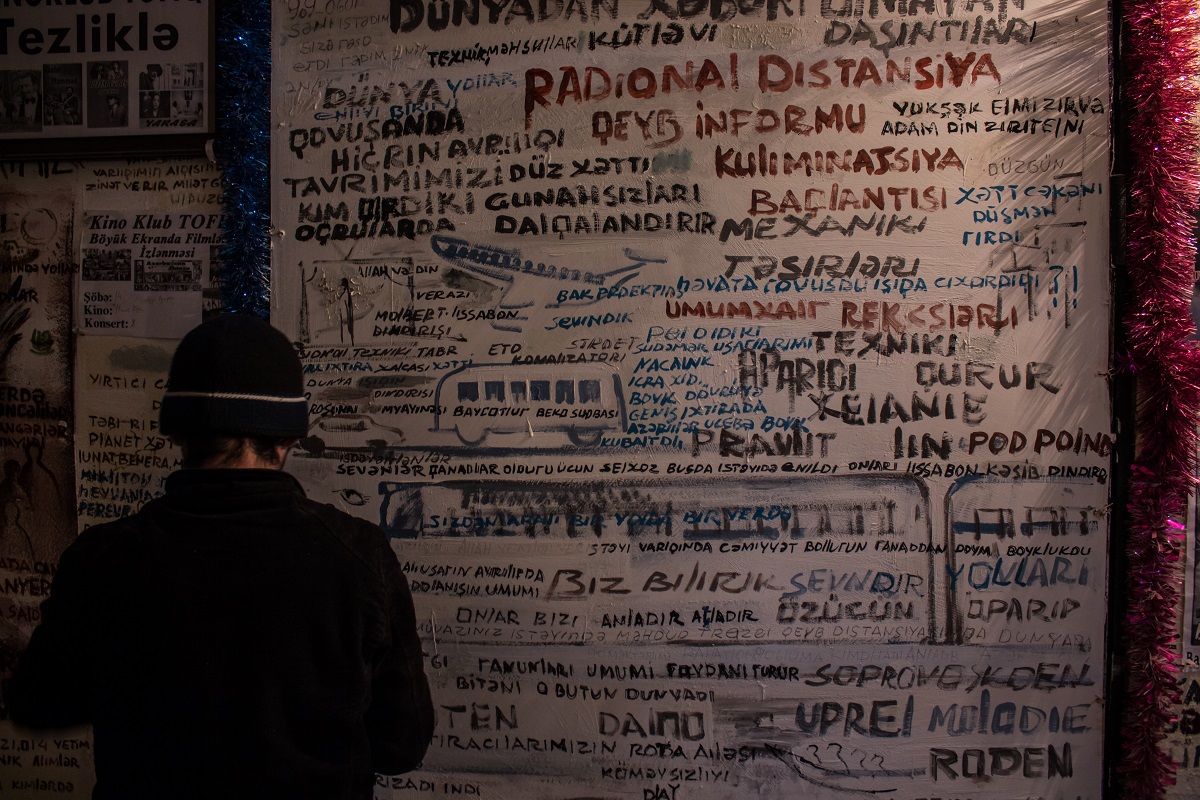

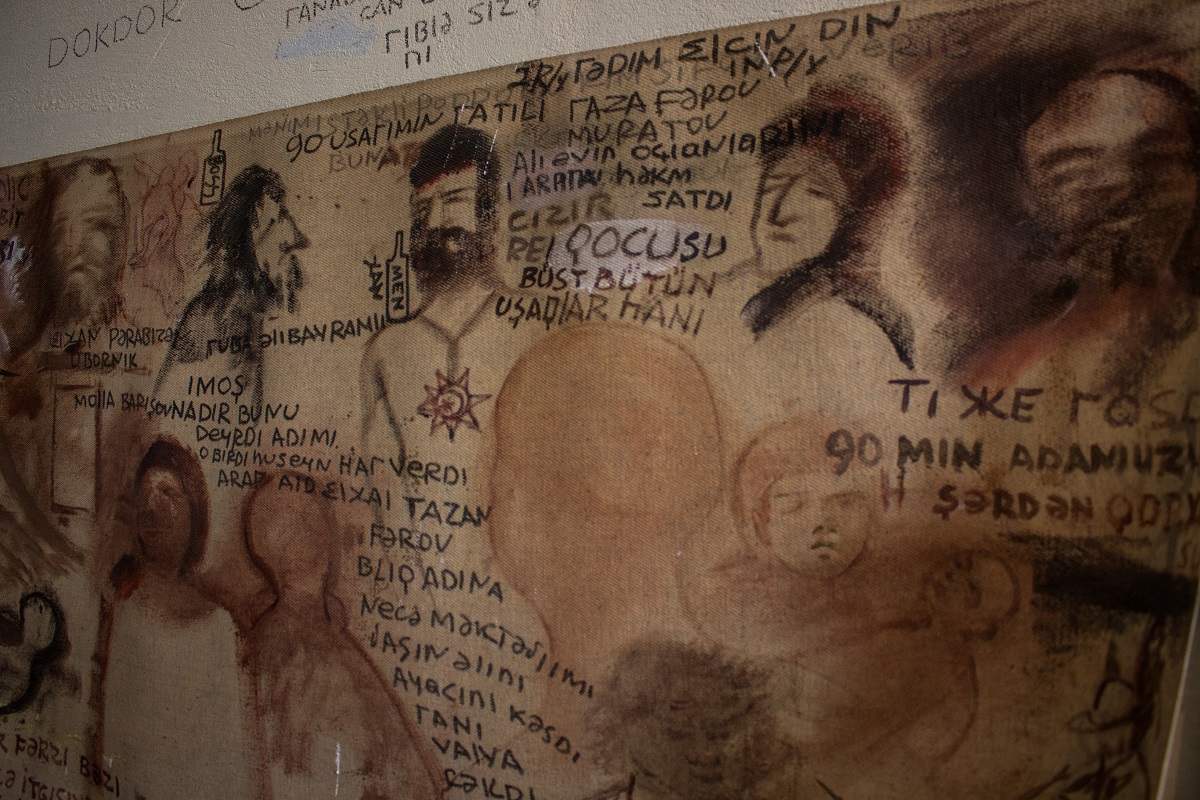

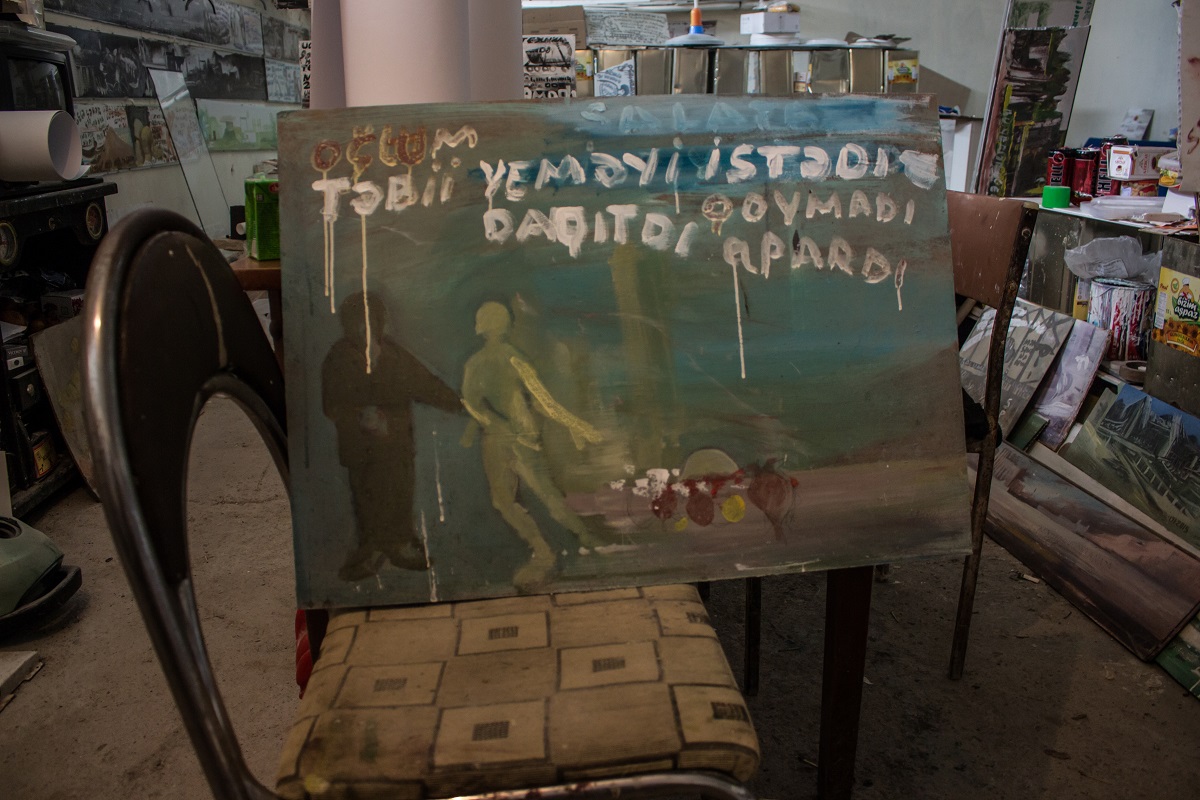

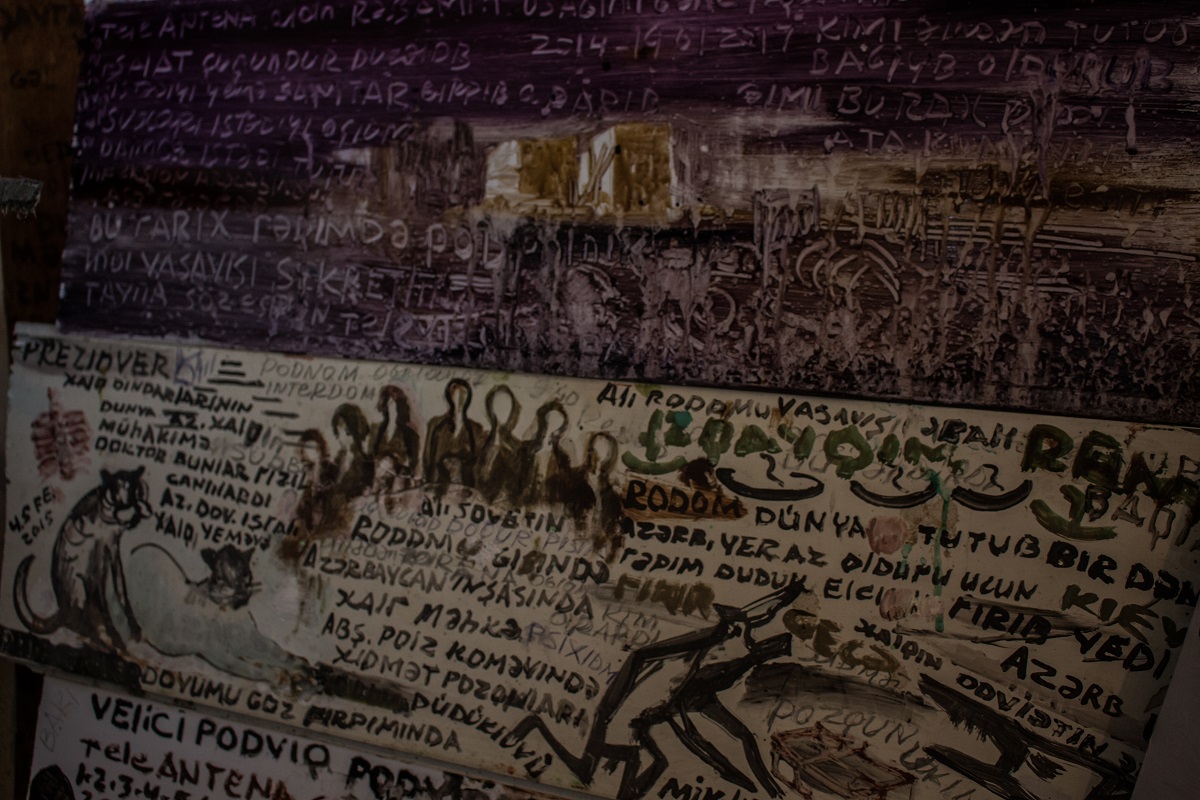

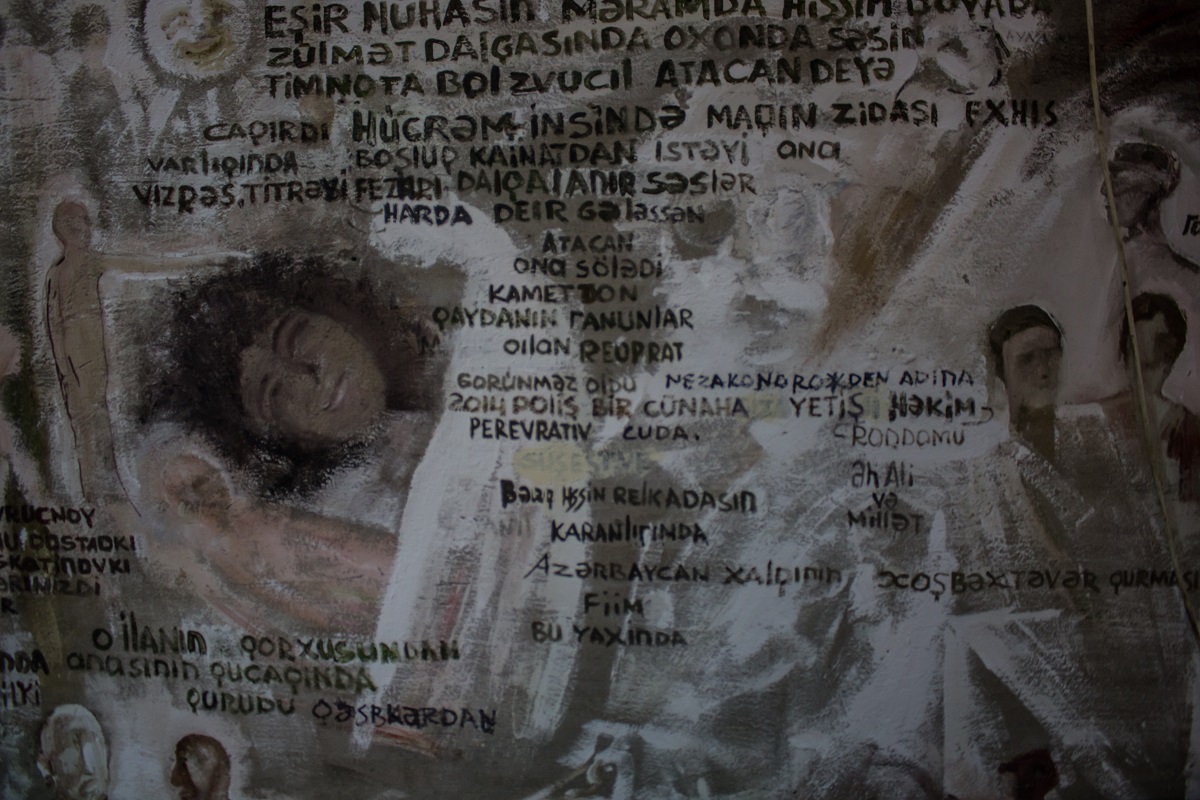

Imran is a patient in the hospital who has special significance as an artist. He works in half-underground quarters with a small hospital film studio. They call this place his workshop. These quarters have been given to Imran because he draws all the time without stopping. He finished art school back when.

Imran has been receiving treatment for more than 10 years, he was brought to the hospital by his wife. His diagnosis – paranoid schizophrenia.

It’s hard to understand what Imran says. And the issue isn’t in the incorrect pronunciation of words. There is schizophasia in his speech – languages and word chains that are often incoherent. Doctors understand just one thing: he is very afraid for a supposed son whom he calls Renat.

Amil

Another artist resident at the hospital is Amil. His diagnosis is severe epilepsy, which is accompanied not only by attacks but also leads to personality changes, explains psychologist Said Huseynova.

He was brought to the hospital because of his constant and uncontrollable fits of aggression and suicidal thoughts. While speaking with Amil, he seems to be a rather well-balanced and well-educated person, however his chaotic inner state is given away by his shaking hands. Amil claims that he feels calm and at peace in the hospital.

Amil has been at the clinic for 15 years, but unlike Imran, he is regularly released home. Because he has severe epilepsy, he has hallucinations during which he hears commands to ‘kill’ or ‘hurt yourself’.

‘Crazy geniuses’

Is there a connection between creativity and psychological illness?

“Both yes and no,” says Agahasan Rasulov. “If someone without particular talents becomes ill with, let’s say, schizophrenia, then it is unlikely they will create something astounding. But talent helps a genius see within him new borders and horizons for creativity. If Amil didn’t have epilepsy, it’s possibly he would have become an artist anyway. But the way he draws now is partially because of his illness – epileptics are known for their meticulousness and their desire to be perfectionists.”

When Amil returns home

Saida Huseynova: “When a person enters a regular hospital, people sympathize with him. When he enters a psychiatric hospital, people are afraid of him. Society places a cross on him. It is not uncommon for relatives to refuse to take patients home, and prefer to put them in the care of the government.

“Doctors call this process stigmatization: when a stamp is placed on people like that, others begin to act with prejudice against them. A former patient might hear whispers behind his shoulders, ‘schizophrenia can’t be cured’ or ‘maybe he’ll become ill again and he’ll kill someone’. In such a situation, society poses more of a danger for the patient than the patient does for society.”