Sharing classroom with your ‘enemy’: how Armenians and Azeris study together in Tbilisi

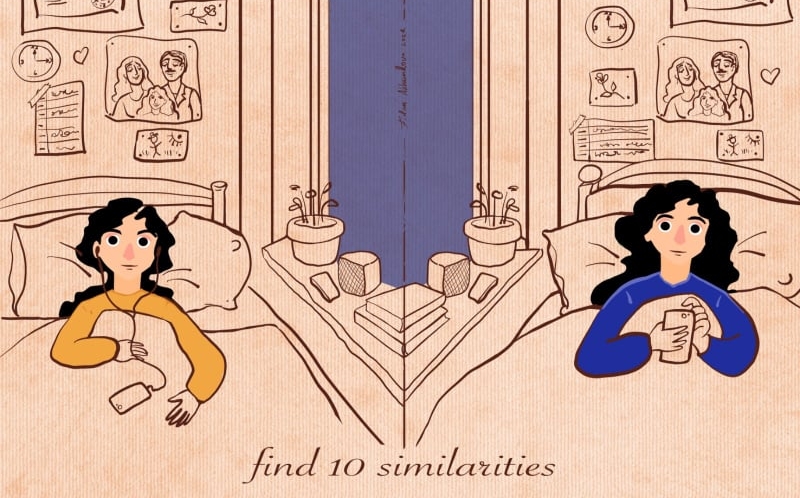

The Karabakh conflict isolated Armenian and Azerbaijani societies from each other for 30 years. While older generation still remembers how the two peoples lived in peace, many young people have never seen their peers from the “enemy” country. Thanks to state propaganda and stereotypes rooted in society, Armenian and Azerbaijani youth treat each other with hostility and wariness.

Studying at foreign universities is one of the opportunities for young people to meet each other in person. For example, since 2001, the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs (GIPA) offers a special master’s program – Caucasus School of Journalism and Media Management, sponsored by the United States. The program is aimed for students from the countries of the South Caucasus,as well as the unrecognized republics of the region.

Arpi Bekaryan

When Arpi first entered GIPA, relations between Armenian and Azerbaijani students in her course developed well.

“The university organized a dialogue meeting for Armenian and Azerbaijani students to help us study and work together in a group, because in previous years there were many conflicts, even fights.

On the second day of the dialogue, when we began to compare our versions of the events around the Karabakh conflict, everything became too emotional, with crying and screaming.

I myself was also in shock, I thought, “Was I really lied to that in my homeland?”

I remember what shocked me the most. When the discussion turned to the Sumgait pogrom, one of my Azerbaijani classmates began to say that the Armenians had committed it themselves. I asked her, “What is the logic in this? Do you understand how effective propaganda is that you don’t even doubt this absurdity?”

Then, after some time, we discussed the Khojaly massacre, and I said that Armenia believes that it was organized by the Azerbaijanis. And then I realized the irony of the situation. They didn’t tell us much either.

For example, in Armenia, history textbooks and the media either ignore the existence of Azerbaijani refugees, or say that Azerbaijan exaggerates their numbers and that they do not want to return home. , I didn’t know anything at all about refugees from Armenia, not from Karabakh.

On the third day of the dialogue, my Armenian classmates and I went to a new meeting and waited for the Azerbaijanis, but no one came. The remaining two days of dialogue took place only between us and the mediators.

Later, the Azerbaijani participants explained this by saying that they did not want to plunge into all these emotions, and we began to communicate again.

We were very close with some Azerbaijani classmates, we even went to Kutaisi together, went to an Azerbaijani restaurant in Tbilisi, and had fun.

But every time the conversation turned to the conflict, I felt that the Azerbaijani friends lacked that dialogue at the beginning.

I myself really wanted to have a normal conversation about the conflict, so during the summer holidays I signed up for a dialogue with the same NGO that GIPA cooperates with to hold dialogue meetings. There I had a great conversation with Azerbaijanis who really wanted to talk.

There were Azerbaijani students from GIPA a year younger. I became friends with one of them, and our friendship extended to his group and to the Armenian students from my group.

In this company, no one became a nationalist during the second Karabakh war, because we talked a lot about it and helped each other get through it all.

My family and friends knew that I was studying with Azerbaijanis, but at the beginning I didn’t talk much about it. They periodically reminded me to “be careful,” and it made me nervous.

When I made Azerbaijani friends, I started talking more about them at home. At first, my mother did not even want to hear their names, she rolled her eyes, but I tried to talk to her more about the conflict, and in the end it changed her.

During the war, I saw on the Internet how my classmates from Azerbaijan celebrated the capture of each village, which really upset me, but my mother suddenly said “you must understand them”.

Now I am only friends with one Azerbaijani guy from our group on social media. We got really distanced with the rest during the war, and with some I was never even friends with on social media in the first place. For example, one girl said that she was going to work for state media and it was dangerous for her to be friends with Armenians.

With another girl, we communicated normally, except for when it came to the conflict, but she is a child of refugees, and I understood her. During the war, she shared militant posts, and when the war ended, she wrote that she regretted that Azerbaijan had not captured Khankendi (Stepanakert). It was personal for me, because my relatives live in this city and during the war I was very worried about them.

I didn’t understand how a refugee child could want the same thing to happen to someone else. I got angry and unfriended her. Now, two years later, I regret what I did. I was too emotional then and would have acted differently now.

Heydar Isaev

Heydar entered GIPA one year after Arpi. According to him, at first, relations between Armenians and Azerbaijanis did not develop very well, because everyone was wary and distrustful of each other, but this did not last long:

“This is all thanks to our teachers, because when they divided us into groups for assignments, they tried to make sure that each group had at least one student from Azerbaijan and one from Armenia.

Thanks to this, we began to communicate more and soon became friends. We started to see each other more, throw parties and celebrate each other’s birthdays.

In our group, on both sides, there were students who were patriots of their countries, were proud of their roots, supported the policies of their states, but we had good relations before the war.

From time to time we had disputes, however, they always took place in a respectful manner and without insults, we always listened each other patiently. This was very different from how Azerbaijanis and Armenians behave on social media, where they regularly insult each other.

Regarding the Karabakh conflict, some Azerbaijanis were belligerent, saying that this was a war and we had to return these lands for our refugees, but the rest, including myself, agreed with the Armenians that these were all just political games, and began to avoid this topic.

We were against the war and wanted it to end as soon as possible. But at the lessons we had to discuss the events in the war or terminology. Sometimes we had disagreements.

For example, I once said that as a journalist I could not report that Azerbaijan had started a war, even if I thought it had. Fellow students from Armenia insisted that there was clear evidence that Azerbaijan started the war. We also argued a lot about the Syrian mercenaries.

After the war, only a small group of Armenians and Azerbaijanis on our course managed to maintain good relations. We were united by the awareness of the cost of this war: after all, each of the Armenian and Azerbaijani students had one of their relatives or acquaintances killed in the war. We are still friends.

Before the war, if I was asked about my position on the Karabakh conflict, I would call myself more pro-Azerbaijani, but during my studies, during and after the war, I became neutral, I do not take sides in this conflict.

During my studies, I began to better understand the human cost of war, because I talked a lot with people from the “other side”.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union