Schoolchildren at war

What do schoolchildren throughout the South Caucasus learn from their textbooks about the three post-soviet conflicts which took place in the region – on Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh and South Ossetia?

The Georgian-Abkhaz conflict

A reference based on information provided by the International Crisis Group (ICG) and BBC:

In the Soviet period, Abkhazia was an autonomous republic within Georgia. The modern history of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict dates back to the 1980s. The larger the end of the USSR loomed, the stronger the tensions became. Abkhazia wanted to become an independent state after the collapse of the USSR. Georgia was intent on ensuring Abkhazia remained its part.

The Georgian-Abkhaz conflict escalated into armed clashes in 1992. In 1994, the Georgian and Abkhaz sides met in Moscow to sign an “Agreement on ceasefire and separation of forces”, a document resulting from negotiations that had been mediated by the UN Secretary General’s special envoy.

The CIS collective peacekeeping forces remained deployed in the conflict zone until 2008. They were solely staffed with Russian military servicemen. At the same time, the UN Observer Mission operated in the conflict area and on the territory of Abkhazia.

After the five-day war over South Ossetia in 2018 August, Russia recognized Abkhazia as an independent country. The diplomatic ties between Moscow and Tbilisi were severed.

As of now, the 1994 ceasefire agreement has been grossly violated on three occasions – in 1998, 2001 and 2008, respectively.

Baku’s version of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict in school textbooks

The only mentioning of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict is in the 9th grade history textbook. It refers to the developments in August 2008 and is just one paragraph.

[su_quote]Quote:“The choice that Azerbaijan had to face in 2008, during Russia’s military invasion into Georgia, was not an easy one. It was important for our country to maintain close cooperation with Russia. At the same time, we also had to defend our key strategic partner in the region. The Azerbaijani government managed to maintain partner relations with Russia, thus ensuring the security of strategic pipelines exporting Azerbaijani oil and gas that passed through the territory of Georgia.”[/su_quote]

The use of the term ‘military invasion’ and the absence of the term ‘annexation of territories’ draws attention.

The developments in the early 1990s are not mentioned in any history textbook in Azerbaijan.

Yerevan’s version of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict in school textbooks

This topic is only mentioned in one textbook – ‘The World History for the Humanitarian Flow, 12th grade’. There are only two paragraphs on the subject mentioned in two chapters, one on ‘The Collapse of the Soviet Union’ and ‘Contemporary Conflicts’.

The schoolchildren are offered the following approach.

[su_quote]Quote:“The autonomous entities were artificially incorporated into some of the former soviet republics. Throughout the years of existence of the Soviet Union, they refused to integrate or merge into those republics, and preserved their national identity. Having proclaimed their independence, they became de-facto independent, but, de jure, they were unrecognized states.”[/su_quote]

Some details are provided concerning the developments in 2008.

[su_quote]Quote:“In August 2008, the South Ossetian conflict grew into Russian-Georgian clashes that lasted five days and saw the Russian troops invade a part of the Georgian territory and stop short of entering Tbilisi. The hostilities ended with the Russian side’s victory.” [/su_quote]

[su_quote]Quote:“The armistice was concluded only through the peacekeeping mediation of the European Union. Russia withdrew its troops from Georgia’s territory and left them deployed in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The Georgian parliament declared the territories occupied, whereas Russia, later followed by Nicaragua, recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent. Up to date, these two are the only states that have recognized their independence.”[/su_quote]

The Armenian history textbooks do not provide any other information on the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict.

Sukhum/i version of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict in school textbooks

The schoolchildren here have been studying the history of Abkhazia from a single textbook for over five years. The textbook author is Irina Kuakuaskir and different sections of the textbook are studied in different grades.

The previous textbook, prepared by well-known Abkhazian historians Stanislav Lakoba and Oleg Bgazhba, was too academic and difficult to comprehend. It was published at the end of the 1980s before the Georgian-Abkhaz war, and was intended for institutions of higher education.

The collapse of the Soviet Union made the Abkhazian Government search for a replacement textbook. In addition, a new subject, ‘The History of Abkhazia’ appeared in schools. It would have been impossible to prepare and publish a textbook adapted for schools within such a short period of time. It was therefore decided to use Lakoba and Bgazhba’s work to fill the gap.

The present-day textbook provides the same interpretation of the historical events as the previous one, except for several new chapters about the Georgian-Abkhaz war and the post-war period in Abkhazia.

The chapters were quite heavy and entitled: “The 1992-1993 Patriotic War of the People of Abkhazia”. The ‘Deployment of Georgian Troops’ in the territory of Abkhazia is interpreted as an act of aggression.

The textbook’s 6th grade section is the first to mention the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. Alongside the official Abkhazian version, the textbook also includes a so-called ‘Georgian’ version of developments.

The schoolchildren report that according to the ‘Georgian’ version, Georgia had to deploy troops to Abkhazia due to constant attacks on trains and looting. Georgia also provided another reason for deploying troops in Abkhazia: the release of two members of the Georgian Government, Alexander Kavsadze and Roman Gventsadze. They had been taken hostage in Abkhazia by supporters of the overthrown Georgian President Zviad Gamsakhurdia.

However, then the textbook’s authors write the following:

[su_quote]Quote:“These were for occupying Abkhazia. The decision on the deployment of troops had been made as early as on August 11, 1992, at the Georgian National Council session. The military operation was entitled “The Sword.”[/su_quote]

The textbook then states that the reason for deploying troops was Georgia trying to put the ‘Abkhaz issue’ to rest. To prove this, the textbook refers to the then-Commander of the Georgian troops Giorgi Karkarashvili who, during his televised address to the Abkhazians, stated that he ‘wouldn’t spare 100 000 Georgians in order to eliminate the entire Abkhazian nation’.

As it is said in the textbook, Georgian troops targeted not only Abkhazians but also the whole non-Georgian population of the republic.

The behaviour of most of the Georgian population in Abkhazia, and its reaction to the launch of war, is qualified in the textbook as ‘the action of the fifth column in Abkhazia’.

[su_quote]Quote:“Numerous publications in the Georgian press testify to voluntary participation of the Georgian population of Abkhazia in the hostilities on the side of the National Council’s troops. The newspapers, magazines, radio and TV assured Georgians that the fight was against ‘impostor Abkhazians’ who wanted to ‘seize’ their native land. There were reports in Georgian press about active recruitment of volunteers to the Georgian military units in Abkhazia,” reads a section of the 9th grade history textbook. [/su_quote]

As the textbook authors defined it, ‘the cruel war, unleashed by Georgia on Abkhazia, will enter the history of the relationship between the two nations as the most tragic page’.

Tbilisi’s version of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict in the school textbooks

The Georgian-Abkhaz conflict is first mentioned in the 9th grade history book, in a section dedicated to the proclamation of the independence of Georgia. The schoolchildren are offered the following version of the developments:

[su_quote]Quote:“In the waning years of the soviet period, due to the mistakes made by the Georgian leadership and with Russia’s active support, the separatist movements intensified in South Ossetia and Abkhazia.”[/su_quote]

[su_quote]Quote:

“The Supreme Council of Abkhazia took advantage of the civil war in Georgia and a temporary boycott announced by Georgian MPs. In July 1992, it passed the Declaration on State Sovereignty of Abkhazian ASSR.” [/su_quote]

It is further noted in the textbook that the Supreme Council of Abkhazia had no right to pass that declaration because of the absence of a quorum. The most important elements and chronology of the conflict were summarised within half-a-page in the textbook. It provides the following information:

In July 1992, the Supreme Council of Abkhazia passed the Declaration on State Sovereignty of Abkhazian ASSR. In August of the same year, Tengiz Kitovani, Georgian Defense Minister, received part of the armaments from the command of the Russian Army’s military district, and on August 14, he deployed national guard troops to Abkhazia where an armed conflict was escalating.”[/su_quote]

[su_quote]Quote:“Several attempts were made during the war to reach an agreement. The Ceasefire Agreements were concluded, with the mediation of and security guarantees from the Russian Federation, in September 1992 in Moscow, and in July 1992 in Sochi, respectively. Both were violated.” [/su_quote]

Surprisingly enough, the information in the textbooks does not change from grade to grade. There are identical brief texts in the 9th and 12th grade textbooks respectively.

Georgian teachers explain such a scant presentation of the issue in schools as follows: The conflict is a political issue and it has not been given a final political assessment. When it happens, it will be reflected in the national curriculum and then the history textbooks will probably be changed. Until then, none of the textbook authors will dare give any clear-cut assessments.

As it turns out from conversations with the school history teachers, some of them are satisfied with the information provided in the textbooks, whereas other teachers independently choose in what direction to conduct their lessons.

Eliso Chubinishvili, a history teacher:

“We, the teachers, explain to children that the conflict became part of the Soviet Union’s criminal policy, when separatism was encouraged and anti-Georgian sentiments were inculcated. Children are also explained that all conflicts in the Caucasus have been triggered by Russia, which pursues its own interests in the Caucasus.”

During the conversation, Eliso Chubinishvili admitted that this was how she herself delivered her classes, rather than taking the general approach of other school history teachers and that ‘the version of history that children hear during their lessons depends on a particular teacher’s views’.

Simon Maskharashvili, also a history teacher, thinks that ‘present-day textbooks, through which the children are taught, serve as examples of anti-textbooks’.

“The essence of the developments in these books are unclear as the cause-and-effect relationships are not tracked. History should serve as a theoretical basis for political doctrines, it should guide the students, explain to them what we have to deal with, what happened and who we are. There is nothing of the kind in present-day school textbooks.”

On the whole, the information about the Georgia-Abkhaz conflict that the Georgian youth receive by the time they graduate school looks as follows:

In the 6th grade, the students learn that Russia has been fighting against Georgia using all possible means since 1801. The children are led to a conclusion that the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict was not a confrontation between the Abkhazian and Georgian people and that the whole situation was instigated by Russia.

Tskhinval/i version of the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict in the school textbooks

The developments are briefly mentioned in a small paragraph in a section entitled ‘The Reasons of the Collapse of the USSR and National Conflicts’ in the 11th grade History book (Russia’s History, the end of 20th-beginning of 21st century). The Georgian-Abkhaz conflict is interpreted in it as a mere consequence of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

[su_quote]Quote:“Hotbeds of tension emerged in Uzbekistan, South Ossetia and Georgia, from which Abkhazia announced it would be seceding.” [/su_quote]

Yelena Yaschina, a history teacher at Tskhinval-based school #2:

“The ethnic conflicts that broke out in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh following the collapse of the USSR are only skimmed over in the textbooks. That’s why we, the teachers, tell the students everything we know about those developments.”

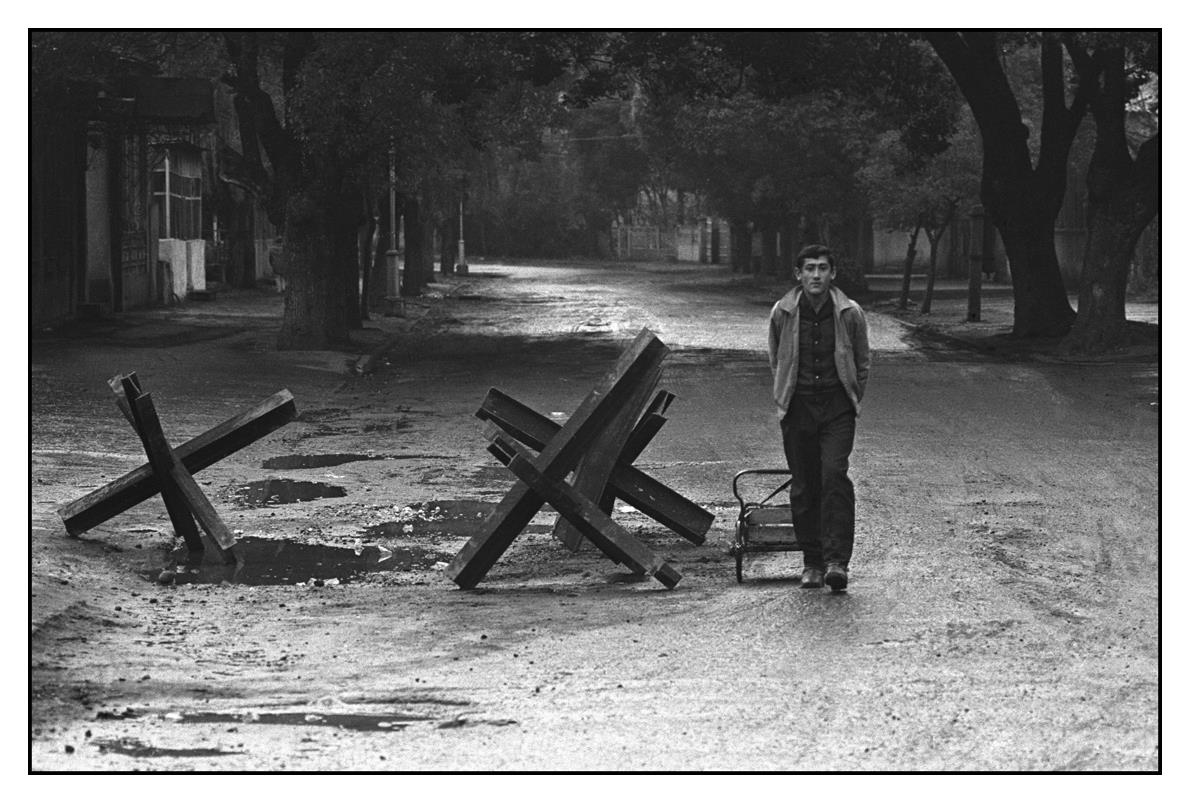

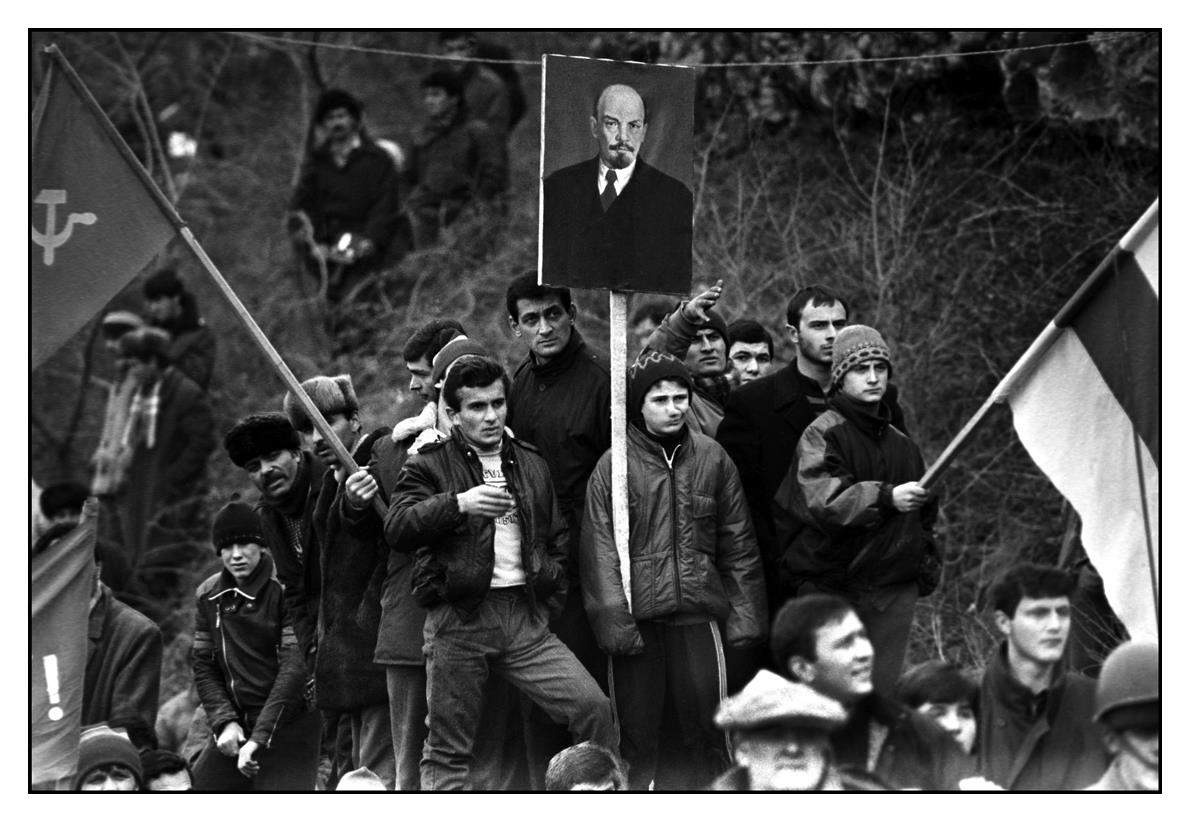

Conflict around Nagorno-Karabakh

Photo by German Avakyan

Baku’s version of the conflict around Karabakh in the school textbooks

The Karabakh conflict is first mentioned in the 3rd grade textbook: “Understanding the World”. The history is presented as follows.

Information about the soviet authorities’ involvement in this conflict appears in the textbooks of the subsequent grades.

February 26, 1992 massacre of civilians in the town of Khojaly is most often mentioned and considered in more detail in the textbooks, including in such subjects as literature and understanding the world.

The history of Karabakh is studied as a separate subject since the 8th grade.

“In the 90s and even in the beginning of 2000s, the syllabus in the Azerbaijani schools was developed based on the old soviet textbooks. The situation started changing long after, says Vahid Samedov, a history teacher.

According to Samedov, the main problem with the history textbooks is that the facts are distorted there: some are slurred over and other are exaggerated. There is a lack of critical re-evaluation. The teaching process is mechanical- this one conquered that one, this one won a victory over that one, he says.

There are some examples in the history textbooks that could be regarded as the language of hatred. For example, those, provide in the 11th grade history textbook.

Here is another example from the 5th grade history textbook:

Pogroms and massacre of the Armenian families in Azerbaijani town of Sumqayit on February 28, 1988, that are often referred to as the fact that made the Karabakh war inevitable, are described in the textbooks as a provocation, purposefully staged by the Armenians themselves.

One more example from the 11th grade history book:

And one more example, this time from the 9th grade history book:

Thus, by the time the Azerbaijani youth graduate the school, they get a clear version of the developments around Karabakh: the conflict was Armenia’s unilateral aggression against Azerbaijan.

Yerevan’s version of the conflict around Karabakh in the school textbooks

Several chapters in the 9th grade textbook in the contemporary history of Armenia are dedicated to the Karabakh war and the history of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, established after it.

This version slightly differs from a brief mentioning of those developments in the textbooks of the preceding grades. It provides the overall chronology of the hostilities and, at the same time, its sections describing the opponent do not contain any evident insults.

One of the most disputable episodes of the Karabakh conflict,the developments in Khojaly, has been included into the topic: “Nagorno-Karabakh Republic It the textbook it is provided alongside the description of the hostilities.

There is a single approach to all Caucasian conflicts in the Armenian school textbooks: the people’s right to self-determination is of higher priority compared to the principle of country’s territorial integrity.

Sukhum’s version of the conflict around Karabakh in the school textbooks

Abkhazian schoolchildren may learn by chance about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict only from the Russian textbooks in general history. The textbook in the history of Abkhazia is the basic history textbook in schools. There is no mentioning of any other developments not related to the Abkhazian theme in them.

Tbilisi’s version of the conflict around Karabakh in the school textbooks

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not studied in Georgian schools. The history of the Caucasus is not studied at all, in general. According to Lamara Keshelava, a history teacher, “throughout the entire 12-year study period, only one lesson in the 8th grade is dedicated to the issues related to Russia and the Caucasus, Shamil and the highlanders. Overall 1-2 hours are allotted for that purpose.

“Therefore, the developments in Karabakh in April 2016 did not cause any interest in the Georgian schoolchildren, says Lamara Keshelava.

Tskhinval’s version of the Karabakh conflict in the school textbooks

Like the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, the developments around Nagorno-Karabakh are mentioned only by one general phrase in the 11th grade textbook in Russia’s history. They are interpreted as mere consequences of the collapse of the USSR.

Georgian-South Ossetian Conflict

Photo by Georgi Tsagareli

Photo by Georgi Tsagareli

Baku’s version of the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict in school textbooks

The 9th grade history textbook provides the first (and only) mentioning of this conflict. And that’s essentially similar cautious phrase like the one about the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict [it could be read above].

The information about this conflict that the Azerbaijani youth possess by the time they graduate the school is as follows: Russia invaded into Georgia (there is no mentioning of annexation of the territory). Although Georgia was a longtime and important strategic partner, the need for maintaining diplomatic relations with Russia did not allow Azerbaijan take any other measures except for its diplomatic support to Georgia.

Yerevan’s version of the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict in the school textbooks

The Armenian school textbooks do not provide separate coverage of the Georgian-Ossetian and Georgian-Abkhazian conflicts. The information on them is presented in the 12th grade textbook in world history for the humanitarian flow and they are described from a uniform position. The conflicts have been generalized to the highest extend and are presented against the background of the global developments, first of all, the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Alike the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, few details about the developments in South Ossetia are provided to students within the context of the developments in 2008. The outcome is summed up in a single paragraph: the hostilities were ceased with the EU’s mediation. The negotiations were launched and the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia was recognized by certain countries.

Sukhum’s version of the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict in the school textbooks

The Abkhazian schoolchildren may learn by chance about the developments in South Ossetia at the end of 80s-beginning of 90s from the Russian textbooks in general history.

However, the chapter entitled “Recognition of the Independence of Abkhazia’, of the 5th-9th grade textbooks in the History of Abkhazia, provides the detailed coverage of the August war 2008.

The textbook section entitled “Georgia’s new aggression provides a detailed story about how that war began.

The Abkhaz history textbook univocally interprets the developments in August 2008 as Georgia’s act of aggression against South Ossetia. The textbook also tells about Russia’s recognition of independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The information about the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict that the Abkhaz youth get by the time they graduate the school looks as follows:

Georgia committed an act of aggression against South Ossetia, whereas Russia was the last to come to rescue and saved the Ossetians from the genocide.

Tbilisi version of the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict in the school textbooks

The conflict is first mentioned in the 9th grade history textbook. A generalized version in a form of one paragraph is given to the schoolchildren.

This paragraph is simply repeated in the 9th and 12th grade textbooks.

Thus, by the time they graduate the school, the Georgian youth are provided with a very brief version of the developments, similar to the information on the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, namely:

The Georgian-South Ossetian conflict was not a confrontation between the Ossetian and Georgian people and the whole situation was instigated by Russia.

Tskhinval’s version of the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict in the school textbooks

There are no school textbooks in the history of South Ossetia, neither is there any separate on this conflict in any other textbooks. The 11th grade textbook in the history of Russia is the only and very brief source of information that is used by the schoolchildren in South Ossetia. The textbook interprets those developments as the consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

В According to South Ossetian school history teachers, they prepare the materials about the contemporary history of the republic individually and at their own discretion.

For example, Yelena Yaschina, a history teacher at Tskhinval-based School #2, has chosen the following succession of events:

“After the 19th century developments we more to the contemporary history and I surely tell them about the genocide of the Ossetians, committed by Georgians in the 20s of the 20th century. Then we discuss with children the developments at the end of 80s and in early 90s, up to 2008.

On a side note, there are stands with brief information on all major events in the contemporary history of Ossetia, mainly the key data, in all schools throughout South Ossetia.

“The courage lessons are conducted in South Ossetian schools several times a year. Those lessons are dedicated to the Independence Day (September 20), the Constitution Day (April 8), and the Homeland Defender’s Day (February 23) –it is believed that on that day, in 1992, the Armed Forces of the Republic of South Ossetia were formed. Specially for this day, the schoolchildren prepare reports and write essays, collect their relatives’ memories, search for Internet information and media articles.

It is expected that the senior grade students will have a uniform textbook in South Ossetia’s history in the new academic year. However, it is yet unknown, how the events will be interpreted and what terminology will be used there.

The opinions, expressed in this article convey the author’s views and terminology do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the editorial staff