Russia revives Soviet tradition: Confiscating oppositionists' property. How does it work?

Property confiscation in Russia

In less than a month, from its submission to the State Duma on January 22 to being signed by President Vladimir Putin on February 14, Russian authorities have enacted a law. This legislation permits the confiscation of property from individuals convicted of “discrediting the Russian army,” inciting terrorism, and promoting sanctions.

The Russian Criminal code previously allowed for the confiscation of a convict’s property in certain cases following the commission of a crime. Now, in Russia, this can be done simply for words spoken on social media. Authorities call this the protection of Russia from “scoundrels and traitors.”

Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer from the human rights organization “First Department,” explained to “New-Europe” that there are three types of property that can be confiscated:

- Acquired as a result of “committing a crime”: fees for articles, monetization from video views, and similar financial incomes.

- Property intended for financing activities against the security of the Russian Federation: money for paying fees, purchasing equipment, etc.

- Any property equivalent to what is subject to confiscation but cannot be seized.

“For journalists, receiving a salary or fee for their work is enough, or an increase in fame that can be monetized. They’ll also come up with something for activists, so I would not like to simplify their work and give them ideas,” says the New-Europe interviewee.

According to “First Department” lawyers, the only way to protect oneself from property confiscation in Russia is not to own any property in Russia.

According to surveyed lawyers, the new law was primarily adopted to intensify the atmosphere of fear in the country and suppress the last possibilities to speak out against the authorities’ actions.

Since 2018 in Russia, more than 116,000 people have been convicted under repressive criminal and administrative articles. About 50,000 of them were persecuted for words.

How exactly the Russian authorities will begin to apply the law is not yet known. Lawyers suggest waiting for the first precedents.

However, some conclusions can already be drawn based on the practice that exists in post-Soviet countries.

Apartments of regime critics for protecting the system

In January 2023, Lukashenko’s regime secretly passed a law on the confiscation of property “exclusively as a retaliatory measure in the event of unfriendly actions against the Republic of Belarus, its legal and (or) physical persons.” It was adopted, of course, “taking into account the need for immediate and effective response to existing threats to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus in the regime of special restrictive measures,” reported by “EuroRadio”.

Economist Yaroslav Romanchuk, in a conversation with DW, noted that the adopted law confirms that there is de facto no private property in Belarus — authorities can “squeeze both business and money” at any time for contrived reasons. Romanchuk predicted that protest leaders would be the first to fall under new repression.

And already in February, the website of the internet auction “BelYurobespechenie” listed a three-room apartment of the leader of the democratic forces of Belarus, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, and her husband, who was sentenced to 18 years in prison on a political charge, Sergei Tikhanovsky.

Commenting on the event, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya said: “This is what politicians who have lost legitimacy turn into: for survival, they commit war crimes, imprison innocent people, send their children to orphanages, steal property, and vandalize homes.” The apartment of the oppositionists was only sold on the third attempt.

In December of the same 2023, Tikhanovskaya reported that Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich’s Minsk apartment could also be seized: “The world-famous Belarusian writer and Nobel Prize laureate Svetlana Alexievich was forced to go into exile (the writer has been living in Germany for four years — ed.). Now the regime threatens to seize her Minsk apartment as another act of revenge. The very same apartment where European diplomats gathered to protect her in 2020.”

“EuroRadio” journalists noted that there was no official announcement about plans to take the writer’s apartment in Belarus. But in the fall, propagandists proposed such a measure.

However, Lukashenko’s regime began to confiscate the property of opposition members before the January law was passed:

- In the summer of 2021, authorities arrested the house of Belarusian opposition figure Pavel Latushko. In January 2022, it became known that an apartment registered to his daughter had been arrested.

- The property (apartment, garage, house, and plot) of the son and daughter of political prisoner Viktor Babariko was arrested.

- The apartment of Alexander Azarov, head of the BYPOL initiative, which includes Belarusian security forces who resigned after the 2020 elections, was arrested.

- In December 2022, a Belarusian court sentenced swimmer Alexandra Gerasimenia to 12 years in absentia for creating the “Belarusian Fund for Sports Solidarity” and calling for sanctions. The court also ordered the arrest of swimmer Alexandra Gerasimenya’s apartment, her bank accounts (over $48,000), a Land Rover car, mobile phones, a parking space, a refrigerator, and a sound system. All of these will go towards the payment of a civil lawsuit. The athlete noted that the apartment was seized even before the verdict.

- The apartment of media manager Dmitry Navosha was also arrested.

A long-standing “tradition”

Belarus and Russia are not the first to use property confiscation as a tool to fight dissenters. In Azerbaijan in 2021, the court decided to confiscate apartments, land plots of the family, and even the house of the parents of oppositionist Saleh Rustamov, who was sentenced to seven years and three months in prison for “large-scale illegal drug trafficking.” In Tajikistan, relatives of oppositionists have been facing threats of confiscation for more than five years.

How Tajikistan threatens to take property from relatives of oppositionists — a few examples.

Already in 2016, human rights organizations Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee stated that the authorities of Tajikistan were confiscating the property of undesirable oppositionists.

After Ilhomjon Yakubov, a member of the leadership of the “Islamic renaissance party of Tajikistan,” participated in a conference on human rights and fundamental freedoms held in Warsaw in September 2016, his relatives in Tajikistan were subjected to systematic persecution by the authorities, and security agencies confiscated homes from the relatives of the oppositionist.

In 2017, Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee reported new cases of threats to families of Tajik oppositionists. Employees of national security agencies and representatives of local authorities of Tajikistan publicly humiliated relatives of activists, did not allow them to leave the country, and threatened them with property confiscation, and in one case threatened to rape the daughter of an activist.

Relatives of Mirzokarim Nazarov, the brother of the country’s former deputy minister of defense Abdulkhalim Nazarzoda, who was eliminated during a special operation after a failed armed rebellion in the fall of 2015, reported in January 2024 that the court issued a new decision on the confiscation of their home.

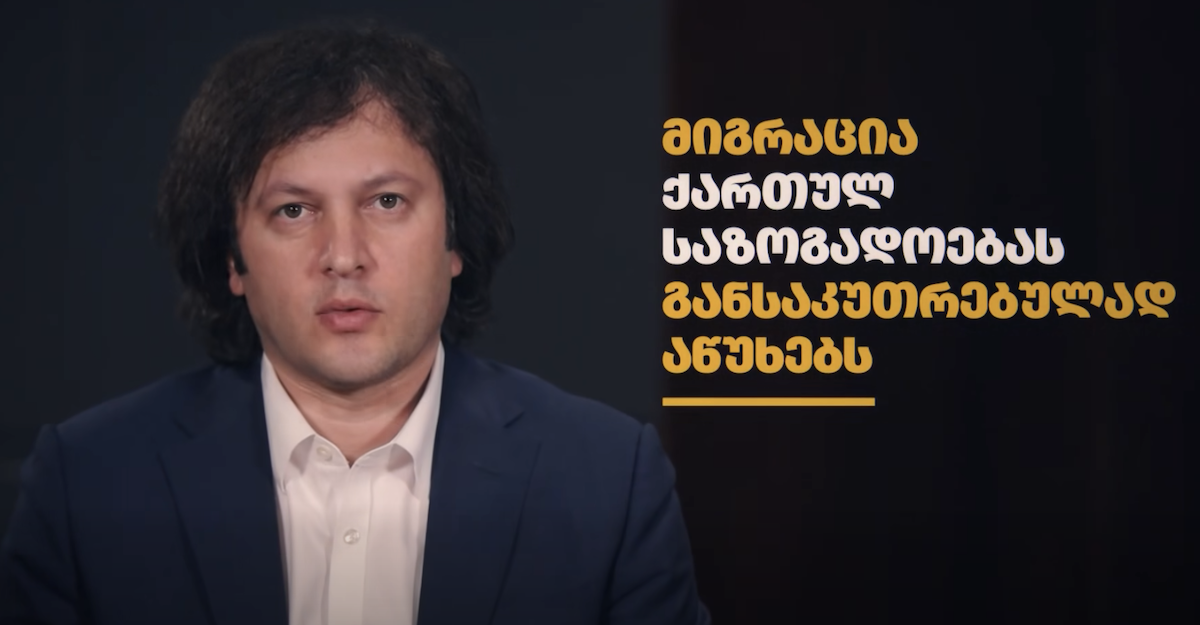

However, Belarus and Russia can be considered among the first to legalize this form of repression. Considering how authorities in post-Soviet countries have taken an interest in the Russian “foreign agents” law (for example, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, the partially recognized Republic of Abkhazia), it cannot be ruled out that they may also take interest in the new practice of pressuring dissenters.