Op-ed: Georgian parliamentary fight discredits country

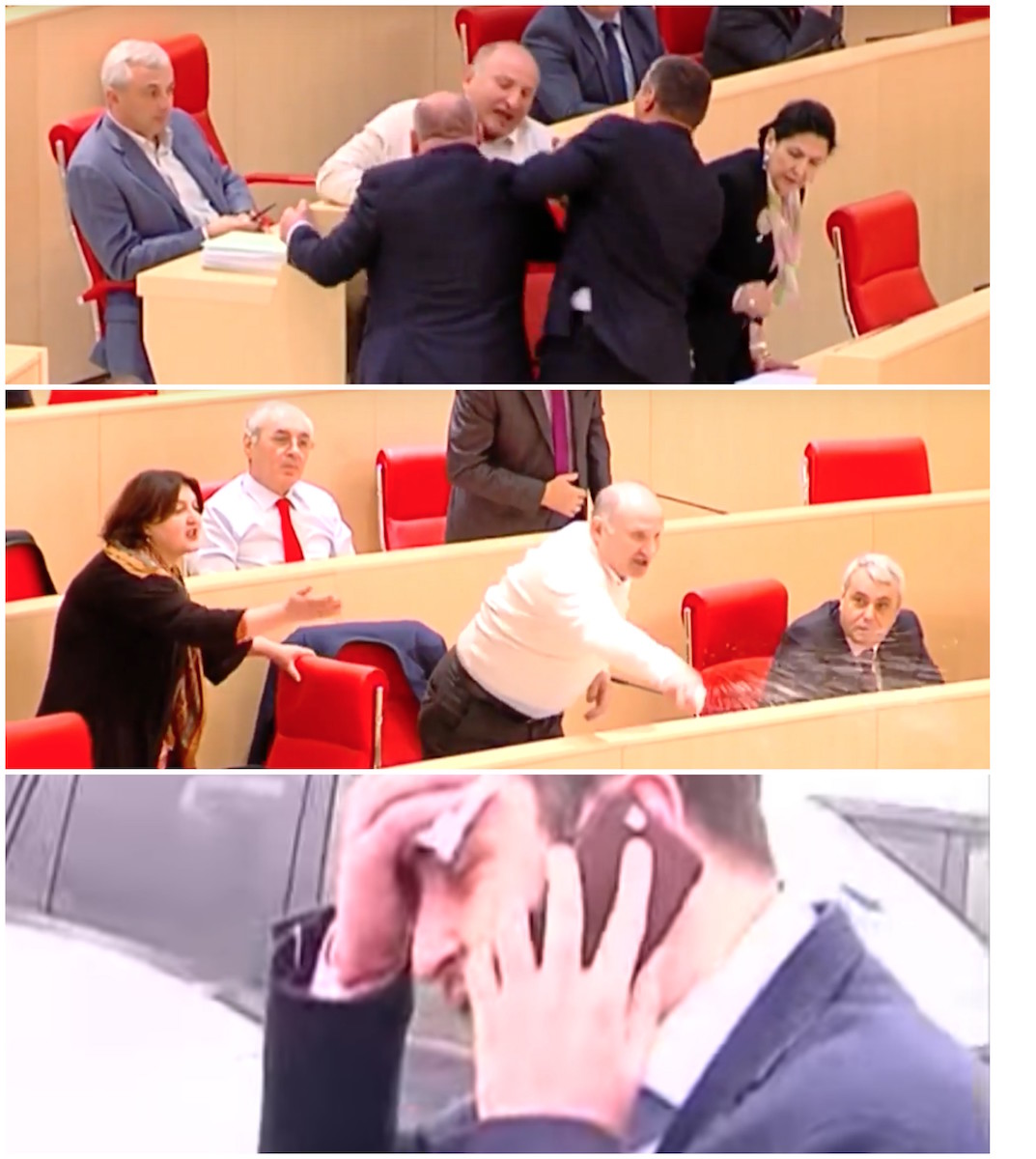

Another brawl in the Georgian Parliament yesterday will perhaps dull the shine of the country’s recent successes, most notably the European Union’s waiver of its visa requirements for Georgian citizens visiting the Schengen Zone. Televised violence between politicians had previously not been seen since the elections of October last year.

There have been few penalties for Georgian public figures fighting in television studios or government buildings, and if any measures have been taken against violent MPs, they have clearly proved ineffective; physical altercations between politicians are – while not overly frequent – entirely expected when those of strongly opposing views clash.

Now, however, in light of Georgia’s progress towards integration with Europe, it might be prudent for the country’s politicians to think about their public conduct, and how it might be viewed by members of the international organisations it aspires to join.

It seems that Georgian politicians cannot break from the idea that what happens in Georgia stays in Georgia, and internal matters (and feuds) should have no bearing on Tbilisi’s international efforts. Last year, the former British Ambassador, HE Alexandra Hall Hall, commented on the abysmal state of Georgian driving, and recommended that traffic regulations be urgently reformed. Ambassador Hall Hall was met with a storm of outrage, which was perhaps only surprising to those unfamiliar with the reactionary Georgian response to criticism, even if – as in this case – it is entirely justified.

Most shocking of all was the response of Salome Zurabishvili, a former diplomat in the service of France, who stated that it was not Ambassador Hall Hall’s place to comment on such an internal issue; the Ambassador was, in fact, as a representative of an EU and NATO state, entirely justified in her remarks.

After all, any Georgian who does not believe that the majority of Georgian drivers, with their total disregard for the rules of the road, would be a hazard in Europe is nothing short of wilfully ignorant.

It might sound trifling, petty, or even vindictive, but Georgia is (and probably already has been) likely to be judged far more for tangible matters related to its people rather than the economic, touristic or judicial figures the government enjoys boasting about to its European elders. While diplomats are people endowed with wisdom who rub shoulders with the mighty in London, Washington, Paris or Berlin, they are people nonetheless, and their lasting impressions of Georgia are far more likely to come from Georgians themselves, and how they drive, or how they treat women, or how they react to an LGBT rally.

The contributions of Georgian soldiers to NATO deployments or the growing tourist industry do not – on a personal level – have the same impact as seeing cars narrowly avoid colliding with each other for the tenth time that day, or hear the many tales of domestic violence that are still told far too often.

It would naturally be wrong of foreigners to judge the country by the conduct of its drivers or the violent behaviour of a homophobic minority, but Georgia’s politicians do not always show that they can stand on any moral high ground. In most countries, public servants and elected officials are some of the best that that nation has to offer, which to anyone unfamiliar with Georgia would (understandably) think is something of a damning indictment of the Georgian people as whole: if politicians – leaders, ministers, lawmakers – openly brawl and hurl objects across the room at each other, imagining the conduct of the average people on the street would set the uninitiated to shuddering.

It is not hard to imagine European MPs, those who have never come within a 100 miles of Tbilisi and work sitting in the familiar comfort of Brussels, watching Georgian politicians scream and shout at each other on the Internet, and then wonder if removing the visa requirement was a good idea.

Yet it is not the duty of Western officials to become familiar enough with Georgia to know that these violent outbursts are not particularly serious (domestically) and do not accurately reflect the Georgian people. It takes years of residence and local interaction to fully understand the social undercurrents and behavioural practices that we call culture, and a Western diplomat juggling matters ranging from Brexit, to how to deal with Putin, to the crisis in the Middle East and everything in between, does not have much time (or interest) to come to terms with the fact that the overweight man shouting and taking a swing at his opponent across the aisle is – despite appearances – not representative of the country as a whole.

It is the duty of Georgia to make sure that its people, and especially its politicians and diplomats, conduct themselves like adults, and show that the country is truly worthy of inclusion with the civilised world.

While the government can talk with a straight face of its ‘partnerships’ with Europe and NATO, these relationships are hardly equal; Georgia needs the West, but whatever the country’s MPs might like to tell themselves – and their electorate – the West does not particularly need Georgia.

With the European Union facing internal crises, the uncertainty of the increasingly-unstable Trump presidency, Russian hostility to its old enemies and the wars of the Middle East, the West has higher priorities than Georgia, even if Georgia has no priorities beyond the West. Now is definitely not the time for Georgia to tarnish its international image.