Misinformation in the Karabakh conflict: analysis of Armenian media from Azerbaijan

Fake news in Armenia regarding the Karabakh conflict and Azerbaijan

Analysis of disinformation spread in the media in Armenia regarding the Karabakh conflict and Azerbaijan. The study was conducted by Shahin Rzayev, Alia Hagverdy and Emil Abbasov, Baku, Azerbaijan.

A similar study by an Armenian author can be found here

About the study

Beginning in the early 1990s the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict has been distinguished by both its military and information/media components; part of which has been the creation and dissemination of disinformation.

Both parties were and continue to be involved in these processes, although the specific tools and campaigns they use differ.

The purpose of this study is to propose methods for verifying information in an environment where fake news and distorted information are pervasive. Researchers in Yerevan and Baku used different methods of fact-checking while studying a number of typical information releases which contained certain elements of disinformation.

Cases related to three serious military exacerbations were taken as examples of fake news in Armenia regarding the Karabakh:

● In April 2016 regarding the line of contact in the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic

● In July 2020 regarding the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan

● The second Karabakh war from September 27-November 10, 2020.

In all cases, and especially in the fall of 2020, there were serious military clashes, resulting in many casualties on both sides. Each of these events were accompanied by an intense information war.

Research shows that fake news during violent battles is often created deliberately by the state propaganda machine. They are also often authored by journalists who confuse their position as a professional and unbiased journalist with that of propagandists and agitators. Many times, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact source of misinformation; in such cases it is likely the result of a “game of a broken telephone”.

Social media has become the primary platform for spreading fake news at this point – though it is via these very sites that one can often find help with debunking manipulative material. A responsible community can often help the researcher find better, more reliable sources, and even provide more accurate photos and videos of the event. Such help has become an important aid to researchers, in addition to more technical means and procedures.

In the course of this study, various methods of collection, processing and evaluation of texts, photos and videos were used, which was especially important, since modern fake news is mainly multimedia in nature.

Many experts consider the second Karabakh war in the fall of 2020 to be unprecedented in terms of the scale of propaganda attacks across both the media landscape and official transcripts/reports. Fake news appeared in such high numbers that it was difficult to separate from real military reports.

The studies prepared by researchers from Baku and Yerevan both use the terminology and toponymy chosen by the authors of said reports.

View from Azerbaijan

Background

The Karabakh war is an armed conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijani that took place in the territory of the former Nagorno-Karabakh autonomous region in Azerbaijan and its adjacent territories in 1991 – 1994. The war was concluded with the signing of a ceasefire agreement, however skirmishes continued from time to time.

As a result of that war, the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region of Azerbaijan and the seven regions surrounding it came under the control of the Armenian forces. The Azerbaijani population was forced to leave these territories.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR), created on the site of the Azerbaijani autonomy, was not recognized by any state in the world, including Armenia. Negotiations on a settlement of the conflict with international mediation yielded no results.

The first outbreak of full-scale hostilities, after the events in the early 1990s, occurred on April 2-6, 2016 and were recorded for posterity as the “April War”, or “four-day war”. Events took place along the line of contact in the Karabakh region.

In July 2020, there were clashes on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Full-scale hostilities from September 27 to November 10, 2020 would be referred to as the “second Karabakh war.” During this time, at least 8,000 people died on both sides, the search for the missing continues at the time of publication of this article.

The ceasefire agreement included as the main points:

● The return to Azerbaijan of control over several areas adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh;

● Russian peacekeepers’ deployment into the region and withdrawal of the Armenian military;

‘● The exchange of prisoners and return of refugees.

From the very beginning of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, in the late 1980s, when news about rallies demanding the annexation of the autonomous region to Armenia began to come from Karabakh, it was impossible to tell the truth from rumors.

In Baku and Sumgait, every now and then, people would openly discuss the horrors with which they were expelled from Armenia (most often from the Kafan region) in January 1988.

These stories were accompanied by a standard atrocious claims that have since pervaded all conflicts, such as: children being buried alive in pipes and pregnant women ripped open.

The death of two Azerbaijanis during the march from Aghdam to Askeran on February 22, 1988, five days before the start of the pogrom in Sumgait, also began to acquire a now typical account of various terrible details regarding abuses by the old enemy.

If in Baku nationalist sentiments were suppressed, then in Sumgait they turned into a bloody pogrom on February 27-29, 1988. Information about the Sumgait massacre spread all over the world, also often acquiring false or misleading details.

Since the outset of the “hot phase” of the conflict, the amount of fake news (the term “disinformation” was used at the time) has increased significantly while it has become more difficult to verify and refute these insidious attacks on reality.

Even in the hottest of times, the exchange of information between the Azerbaijani and Armenian media was supported. Turan and Khabar-Service news agencies exchanged news with Armenian colleagues from both Snark and Noyan Tapan agencies.

Later, after reaching an agreement on a ceasefire, other publications also joined this initiative. One of the most successful examples of cooperation between journalists was the project of the Swiss organization CIMERA (1997-2000), within the framework of which, Azerbaijani journalists were able to visit Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, and Armenian journalists came to Baku.

At the time, the leadership of Azerbaijan did not interfere with such joint projects.

For example, then President Heydar Aliyev said, at a meeting with Armenian and Georgian journalists in Baku (early June 1999):

“The fact that journalists have undertaken such an exchange serves our strategic goal. I see this not as some kind of meeting of journalists, but as a link in the chain of measures that we must carry out in order to establish peace in Transcaucasia” (“ Bakinsky Rabochy ”newspaper, June 3, 1999).

After the death of Heydar Aliyev, Azerbaijani leadership has taken on a much tougher position regarding both journalists and Armenia. Visitor exchanges between journalists have almost ceased, while their programs and products have become heavily censored.

Since the end of 2014, pressure on the civil sector has significantly increased in Azerbaijan. Almost all sources of funding for independent NGOs were cut off. The then chief of the presidential administration, Ramiz Mehdiyev (now disgraced), dedicated an 18-page article-published in almost all pro-government publications-in which he declared foreign-funded independent NGOs “the fifth column designed to undermine stability in Azerbaijan.”

The authorities simply adopted the Russian experience and feared something similar to the Ukrainian Maidan revolution. Since then, in order to receive a grant, it was necessary, not only to officially register an NGO, but also to register the grant itself with the ministry of taxes, the ministry of justice.

And if an NGO has a head office in another country, then also with the ministry of foreign affairs. The procedure has rendered registration and operations of NGOs almost impossible.

Since then, many independent NGOs have been forced to curtail their activities, or close down altogether. GO NGO has remained mainly loyal to the government.

These circumstances are the reason that in Azerbaijan there are almost no organizations engaged in fact-checking at a professional level, which has created additional difficulties for our research.

The situation is similar across all forms of media. There is no free advertising market in the country, and many publications survive through public (through the State Press Support Fund) or covert (through dummy commercial firms) funding.

In both cases, the source of funding is the government, and naturally, loyalty is required in return. Media and websites that do not meet these requirements are either blocked or closed.

At the same time, the growth of social networks and new media made major changes in the tactics of waging an “information war”.

Each new aggravation along the front lines was accompanied by rumors. Independent journalists were banned from traveling to the front lines without permission from the Ministry of Defense, making it nearly impossible to verify facts on the spot.

All this has led to Azerbaijani media taking information from Armenian sources. Even now, Azerbaijani agencies refer to the posts of Armenian officials on Twitter and Facebook, while the press services of government agencies are very late in responding to events (with the exception of the press service of the Foreign Ministry).

The lack of information and the ability to check unbiased news was particularly affected during the most serious escalations in Karabakh throughout April of 2016.

On social networks, one of the main topics of dispute between Armenians and Azerbaijanis was the question of “who shot first”. Both the authorities and residents of the front-line villages unanimously accused the enemy.

Information war between Azerbaijan and Armenia

Armenia and Azerbaijan became enemy countries after Nagorno-Karabakh, a former autonomous region within Azerbaijan, came under the control of Armenia as a result of the hostilities of 1991-1994.

Since then, since there is no full-scale military action, the conflict is considered frozen while both countries are waging a fierce information war.

The difference between the media strategies of Armenia and Azerbaijan is, first of all, in how they work for an international audience.

Armenia is trying to strengthen its image and position in order to be able to count on the support of the international community in the Karabakh conflict. The image of a small but civilized Christian state that survived genocide is strengthened by a powerful diaspora around the world.

Azerbaijan prefers expensive information campaigns aimed directly against Armenia – like the Justice for Khojaly campaign, when billboards and events were lit up many cities around the world.

By the same principle, the messages of Azerbaijani propaganda aimed at an external audience are, most often, an attempt to “respond” to Armenia.

As for the internal audience – here the authorities incite hatred of the “enemy” in ways comparable in both their directness and their clumsiness. The only difference is that the Armenian authorities use more modern methods – for example, posts on social networks.

Nature and subject of fake news

During the fighting along the line of contact (or on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, as in 2020), the bulk of the information that the sides are “passing over the fence” is not from deliberately invented or altered facts, but rather the reinterpretation of existing facts to match their own benefit.

A huge amount of political “analytics” are usually published, proving that the enemy is somehow simultaneously cunning and cruel, but at the same time pathetic and weak.

For example, around the beginning of clashes on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in July 2020, one of the Armenian websites writes:

“Perhaps the Azerbaijani military got lost while under the influence of alcohol or drugs“.

Accordingly, fake news discussed:

1. The enemy’s losses (which are being hidden) such as an allegedly downed Azerbaijani drone, which we will discuss in more detail later.

2. Our own military successes.

3. The inhumanity and immorality of the enemy – fake stories about how badly the enemy’s army treats its own soldiers, and so on.

4. The enemy’s cunning plans – for example: suspicious preparations on the front line or internal correspondence of state structures.

Sources of fake information

False information appeared throughout the periods of violence at all levels; from “amateur performances” in social networks to official messages. Often these can be entire sites or social media accounts created specifically to spread fake information on behalf of the “enemy”.

Sometimes fake news picked up by the media and social networks from abroad. For example, fake news from Russian sources, is often spread widely.

In general, both in Azerbaijan and Armenia, state propaganda and social networks begin to work together during periods of escalation. And, in both Azerbaijan and Armenia, government agencies, usually, officially urge citizens on social networks “for national security purposes” not to engage in amateur reporting. Their goal being to establish something akin to a monopoly regarding the control and distribution of information in the war for hearts and minds.

As for fake news specifically created by the “official” propaganda machine and spread through social networks, this phenomenon is rare in Azerbaijan, compared to Armenia.

Examples of fake news

Let’s consider and analyze examples of fake news during the Karabakh conflict, from 2016 – 2020.

Downed Azerbaijani drone Hermes-900 in July 2020

“The Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Armenia has published a video of the destruction of the Azerbaijani drone: Elbit Hermes 900″ on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border.”

The news was published on July 14, 2020, two days after the start of clashes on the border of Azerbaijan and Armenia.

This news was picked up by Armenian media, along with a video where the drone was allegedly shot down. However, it appears to the naked eye that the camera is actually filming a passenger plane.

These sites refer to comments then press secretary of the Minister of Defense Artsrun Hovhannisyan

The website of the Armenian Ministry of Defense also has information regarding the downed drone.

Azerbaijanis flee from frontline villages in panic (July 2020)

Armenian media covered this headline during the July escalation of fighting, on July 19, 2020:

“As the correspondent of Tolish Media reports from Tovuz, panic and chaos reigns in Azerbaijani villages bordering Armenia“.

However, if you pay attention to the source, it is a strongly oppositional website blocked in Azerbaijan, which positions itself as the media of the Talysh national minority.

And the source of the photo is oxu.az, a site loyal to the government, which would never have filmed the stampede of residents, even if it happened.

As the same oxu.az later stated, the residents of the village do not run anywhere on the website, but gathered at the entrance to the village to greet the Azerbaijani military. This version is supported by the fact that there are only men in the photo.

If Armenian journalists set themselves such a task and if Azerbaijani journalists agreed to cooperate, it would be easy, with the help of one phone call, to clarify what is happening in the frontline villages.

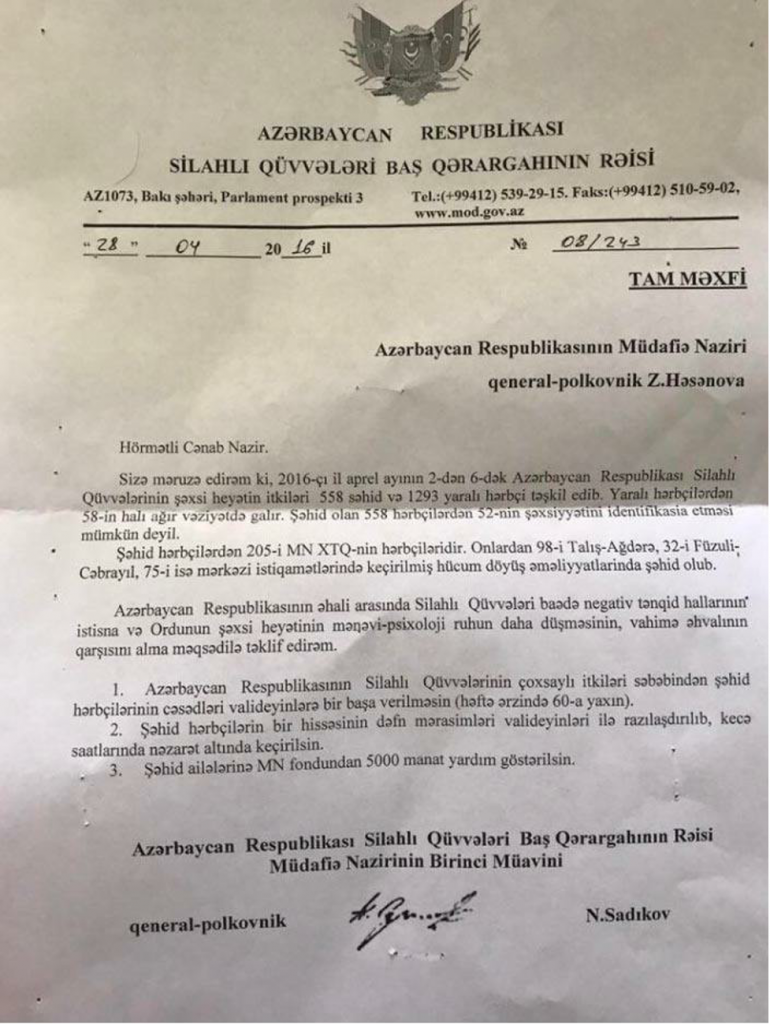

“Letter from the Chief of the General Staff of the Ministry of Defense of Azerbaijan, Nejmeddin Sadykov” (2017)

In early 2017, a photocopy appeared in the Armenian media of what was allegedly a letter from the Chief of the General Staff of the Azerbaijani Armed Forces, Najmeddin Sadigov, addressed to Defense Minister Zakir Hasanov.

In it, he allegedly proposes to hide the number of victims of the operation (we are talking about the four-day April war of 2016), to bury the corpses at night and give the relatives 5,000 manats [about $ 3,200] compensation for silence.

There are 17 spelling errors in the text of the above mentioned letter. On the “letterhead” of the “official” letter, instead of the official logo of the Ministry of Defense, there is an emblem taken from the Wikipedia article entitled “Azerbaijan Armed Forces”.

In internal correspondence of the defense department, the use of official letterheads is not practiced – they are used only in interdepartmental correspondence.

This fake, apparently, was made for an internal audience, therefore knowledge of the Azerbaijani language is enough to expose it.

Another stampede – fake news imported from Russia (April 2016)

In this video, filmed in Azerbaijan by Russian journalists during the April 2016 escalations conflict, the correspondent claims that Terter residents are so afraid of shooting that they live in cars outside the city.

At the same time, the video shows standard parking practices in the background. The man being interviewed says there are victims and that they are returning from a funeral.

On top of his voice, a voice-over translation was superimposed, which has nothing to do with the original:

“There are several families of us here, our neighbors are from the street. By evening there will be more cars. ”

After this story, the correspondents of the “Life News” channel were expelled from the country in disgrace, but before that, Armenian media managed to widely replicate and distribute this video. Life News, owned by businessman Ashot Gabrelyanov, existed for 4 years and closed in 2017.

Highlands captured by Armenian troops (July, 2020)

This news appeared during the July 2020 escalation of tensions.

Armenian websites reported that the Armenian armed forces had occupied the strategic heights of Garagay. As evidence, a photograph was given, allegedly taken from this very point.

However, this photo shows the date and coordinates. The date shows that the photo was taken in December 2018, and the coordinates indicate that this location is within Armenian territory.

Allegedly shot down drone (July 2020)

This photo was published in 2020 during the “July battles”. Armenian media, including public radio, accompanied this photo with a note that an Azerbaijani drone was shot down.

The Azerbaijani Defense Ministry quickly exposed the fake, claiming it was a photo of an American drone shot down in Pakistan in 2014.

However, the photograph is actually even older – it first appeared on the Internet in 2008 at flightglobal.com, a website about the aviation and aerospace industry. This poor little machine has been playing the role of a downed drones from a myriad of states since 2009.

The flow of fake messages during the second Karabakh war

During the 44-day war in Karabakh, fake stories appeared in such numbers, that they were difficult to distinguish from real military reports.

The propaganda from the Armenian side, including fake news, was directed at the hearts and minds of domestic and international audiences rather than attempting to “intimidate the enemy”.

Naturally, most of the false narratives concerned news from the front: exaggerating the losses of the “enemy” while, at the same time, exaggerating their inherent cruelty.

Another feature of this period: even experienced journalists were inclined to believe any news about the cruelty and cynicism of Azerbaijanis, because both societies were obsessed with their ancestral hatred for one another like never before.

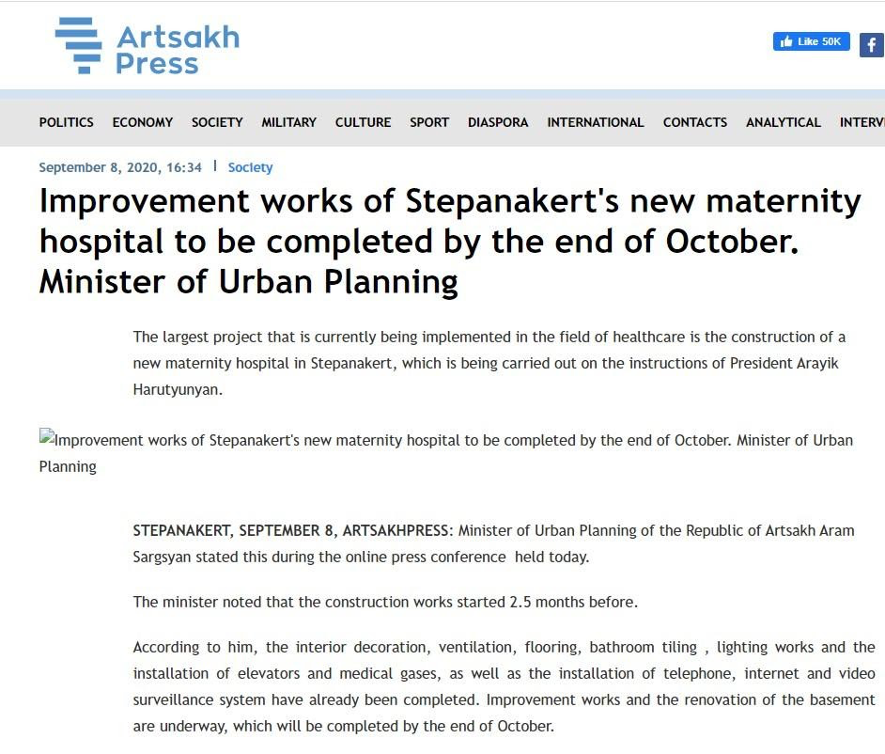

Maternity hospital in Stepanakert (Khankendi) was shelled, October 2020

The news that the Azerbaijani military fired on the Republican maternity hospital in Stepanakert (Khankendi) at the end of October 2020 quickly spread across Armenian social networks.

Both reports in the media and comments on social networks were full of indignation at the shelling of the hospital, and they were accompanied by footage of the destroyed building.

“It is reported that the main blow fell on the building where the hospital was located … The pictures show a dilapidated building with collapsed ceilings and destroyed walls.

This, of course, is a complete disaster. There are no military facilities nearby, wounded civilians are brought there, gravely ill patients are sent from there to facilities deeper within Azerbaijan, proper,” commented the military commander Alexander Kots indignantly on his Telegram channel Kotsnews.

Yes, all these photos show that this is a hospital, but you can also notice that it is “not inhabited”. There is no furniture, no equipment, no other signs of the presence of people.

The hospital was indeed fired upon, but it still did not function as a maternity hospital, as it was commissioned only at the end of October.

Here is a photo of said hospital at the very beginning (2018)

And here is a photo after being hit by a rocket:

Here you can see that this is the same building, and you can see that it was never completed, if you pay attention to the flight of stairs on the left.

“Medal to the athlete“

Serge Tankian is one of the world’s most famous rock vocalists. He shared this tweet:

Kamil Zeynalli, Who Participated In The Beheading of An Old Man During The War, Awarded A Medal In Azerbaijan. pic.twitter.com/RYc45AqHo6

— Zartonk Media (@ZartonkMedia) February 6, 2021

Zartonk Media is an English-language resource very popular among the Armenian diaspora (of which Serge is a prominent representative).

Thus, the news consists of two statements:

1. Kamil Zeynalli participated in the hideous execution of an elderly man, which was filmed and posted on the network.

2. He was awarded for this heinous action.

In Azerbaijan, society reacted aggressively to this video – many claimed that it was a fake, but no one could convincingly prove anything. No names have ever been named in connection with it.

Kamil Aliyev is a fitness trainer and participant in several television shows. Before and during the war, he was actively involved in charity work, specifically helping veterans. The medal, that Zartonk refers to, was given to him by a non-governmental organization for giving aid to veterans of the Karabakh war.

A quick check as to whether such a medal even exists in Azerbaijan, reveals that there is no official mention of this particular ‘honor’.

A google search of the name of this medal shows that it directly related to an NGO working in the region.

Furthermore, it turns out that Kamil Zeynalli is not exactly a favorite of the authorities much less a hero, but importantly, from time to time he was detained for hooliganism, for violation of quarantine, and in early October 2020, served 10 days in prison for filming illegally at the military front.

In December, Zeynalli was detained for 30 days for trying to take food to the military based in the Kelbajar region. He was detained as he attempted to pass through a police checkpoint without special permission. That is, he did not have access to the front-line and, in principle, there was no opportunity to commit any war crimes in the first place.

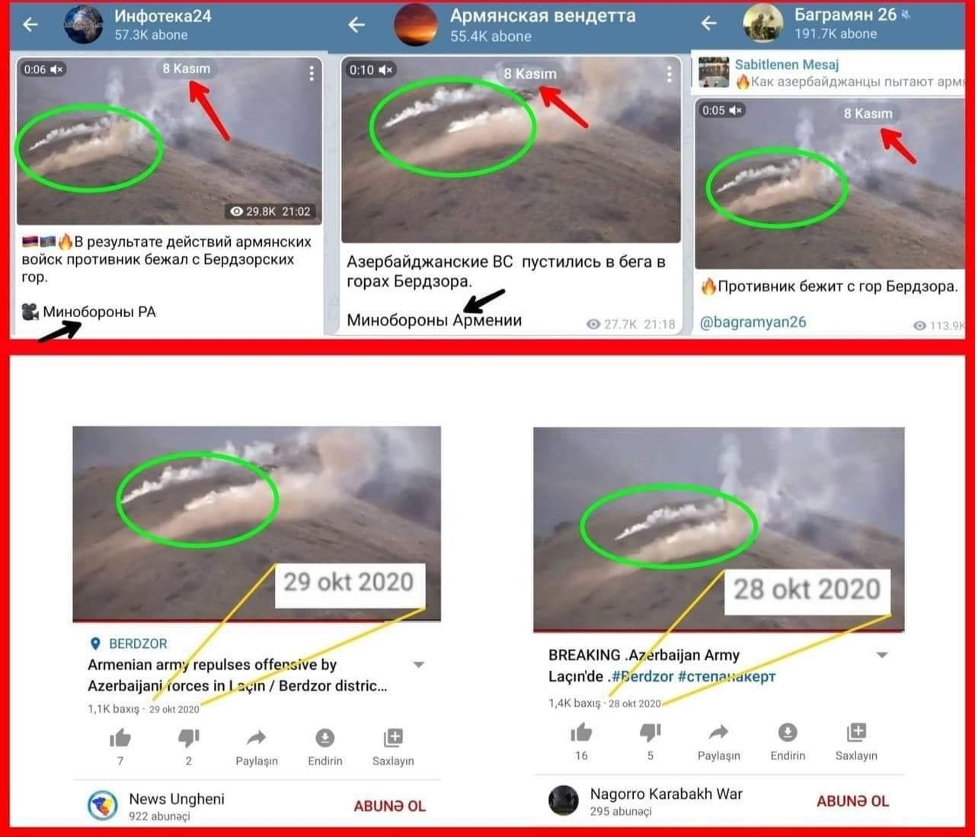

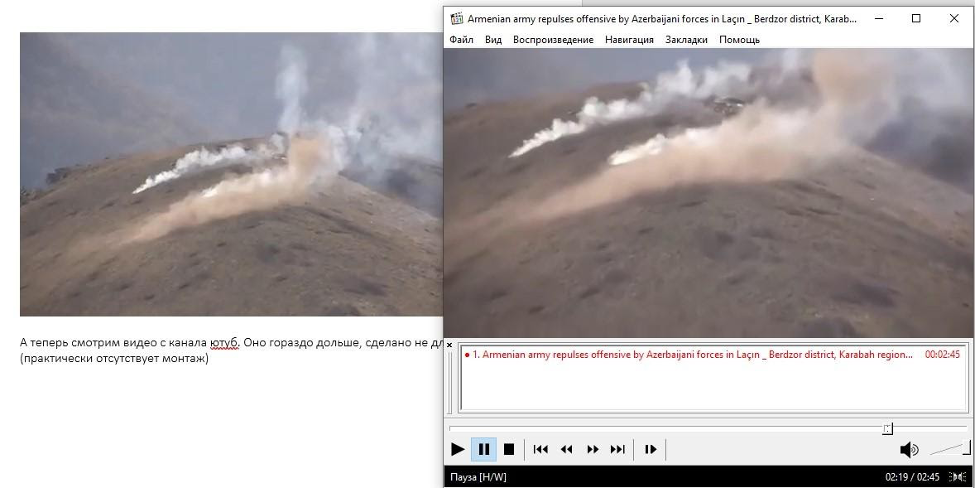

“How long can you run away?” November, 2020

Shortly before the end of the war, on November 8, the following news appeared across Armenian media, as well as on Telegram channels:

“As a result of the actions by the Armenian army, the enemy fled from the Berdzor mountains“.

As evidence, a video by the Armenian Ministry of Defense was attached to the article wherein people who’s identities cannot be verified are viewed running down a hill.

If you search for tags in Telegram, or do a keywords search in youtube, you can find the same video uploaded much earlier. It is enough to prove that the video of November 8 was edited from a pre-existing video, therein proving this new video to be a fake.

Download both videos and compare.

This video from telegram contains closer images of people running, but at 44 seconds this frame appears. It lasts less than a second.

Here we have a video from YouTube. Much overlaps, but it could be the same place. Were it not for the completely identical three puffs of smoke, one might consider this a mere coincidence.

The Azerbaijani site 1news has been closed? September, 2020

One of the most important issues that tormented both sides throughout the war is the actual death toll. There were two diametrically opposed positions – complete silence (with the exception of the death of senior officers) on the part of Azerbaijan and a detailed list, which was updated daily – in Armenia.

The website politik.am published this article:

This form of fake news is designed primarily for their internal audience:

1. Although the screenshot of the 1news site repeats its design, nevertheless, if you look closely, all the inscriptions there are in Armenian. It can be assumed that this was done “for translation” to the Armenian side, but the POLITIK website itself, like 1news, is in Russian.

2. Everyone in Azerbaijan knows 1news. This is the largest media resource, , completely controlled by the state, and not just “one part of Azerbaijani media”. If they published such scandalous data, contradicting the official, even for half a minute, the news would immediately spread to all other sites in the country, and 1news itself would cease to exist.

But even though the fake news says that the site does not work at all, a quick Google search of “1news” and “September 29” (and “September 30”) and we see that it functioned at the time of publishing.

The wider public in Azerbaijan became aware of this fake news attempt after a rebuttal from 1News itself.

“We are all” website, September, 2020

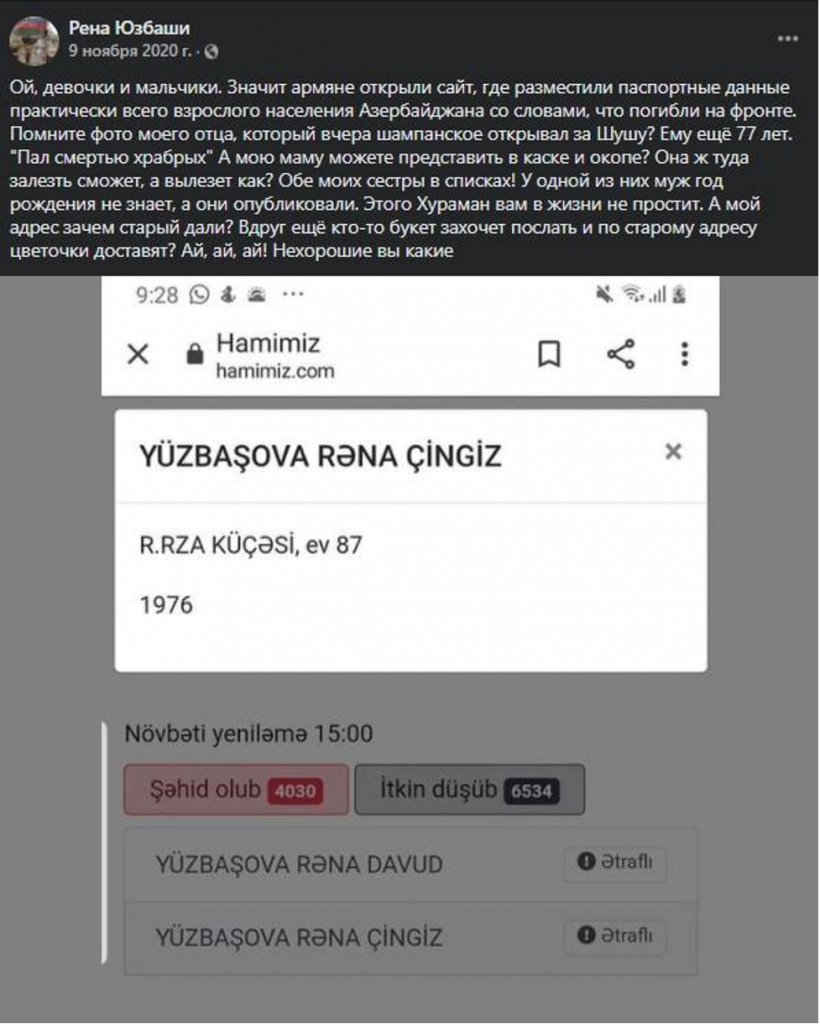

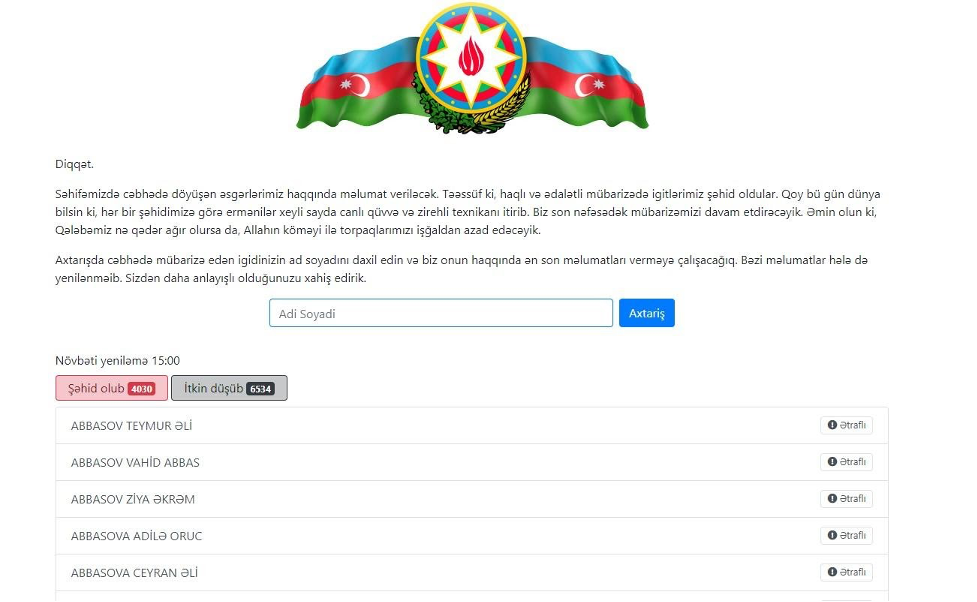

One particular Fake News incident exploded throughout the Azerbaijani community – the site Hamimiz.com (translated as “We are all.”) published a list of those killed and missing.

People started to visit this site, looking for acquaintances with many even searching for random people or themselves on the lists. It turned out that these lists included “all of us” as many citizens found not only their dead relatives, but their very much living friends, and even themselves amongst the casualties.

It is not known how effective this particular fake was, but that it was one of the largest is for certain. They even made a TV report about this.

However, it is believed that, in addition to panic, this fake was aimed at collecting whatever data citizens could share by entering their first and last names.

While, this site does not currently exist, you may use the Wayback Machine service, and see what it was like.

“Protests demanding the resignation of President Ilham Aliyev” November 2020

This video was circulated on social networks with the comment that it was in Baku that protests demanding the resignation of the president were taking place.