Losing and finding one’s loved ones

‘Hello Mama Lyusya,’ on the other end of the line was an unfamiliar woman’s voice.

‘I’m no mother to you!’ Lyusya retorted. It must be some sort of practical joke. But the caller turned out to be Kostya’s mother.

The call would eventually lead to Lyusya being reunited with her grandson.

For some twenty years, the woman had been living with the uncertainty of not knowing what had happened to her son and grandson. And if, after seventeen years, she and her grandson were finally reunited, her son’s fate still remains unknown.

Over the course of her life, eighty-one-year-old Lyusya Avanesyan has lived in three places. Born in Nagorny Karabakh, she grew up in Baku. For the last twenty nine years though, she has been living in Vardenis, a town in Armenia’s Gegharkunik Province.

Lyusya lives alone in her flat in Vardenis. ‘These are my men,’ she says, pointing at three portrait pictures in the living room.

The portrait in the centre shows Lyusya’s husband, who died when she was forty years old. The next picture is of Lyusya’s older son Borya, who died in 2008 after a protracted illness. The final portrait shows Lyusya’s younger son Edouard. For twenty four years, she has had no news of him.

Edouard Avanesyan was born in Baku in 1959. As a young man, he moved to Russia, and had planned to settle and work there. When the conflict in Nagorny Karabakh broke out, Edouard went off to fight. In 1999, he was declared missing in action.

Delegations of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Yerevan and Baku and the ICRC mission in Nagorny Karabakh have registered more than 4,500 military personnel and civilians, declared missing as a result of the conflict in Nagorny Karabakh. More than 400 of them were registered in Armenia. Around the same number have been declared missing in Nagorny Karabakh.

In 2014, the ICRC began collecting DNA samples of relatives of people who had been declared missing. Since the project began, DNA samples of 1,077 blood relatives of 344 people declared missing have been taken in Armenia. DNA profiles have been created for 195 of the samples. These have already been tested in an independent laboratory. Thanks to these samples, the identification of exhumed remains should become an easier task.

• An Armenian village chooses to maintain an Azerbaijani cemetery

Grandma Lyusya mixes the Karabakh dialect with Russian. In Baku, she says, they mainly spoke Russian.

Before the conflict in Nagorny Karabakh, she recalls, Armenians were treated well in Baku. Lyusya herself had worked at a knitwear factory. She had been given a flat, which her sons had renovated.~

But in the early 1980s, everything had changed.

‘My son Borya was a taxi driver. He often had to go to Sumgait, and he used to tell me that we should leave. I kept telling him not to worry. I believed that everything would work out. But it didn’t,’ Lyusya recalls.

Eventually, like many Armenians from Baku, she was forced to exchange her flat and move to Vardenis.

By then, her sons had moved to Russia. Lyusya could have joined them, but she feared that similar events could take place in Russia, too. ‘If that happens, at least my children will have a home here. That was the thinking behind my decision to exchange our flat.’

Events took a different turn, however. In 1991, Lyusya’s older son Borya decided to return home. A year later, Edik (Edouard) and his partner Natasha joined them.

‘Then he told me he had to go to Yerevan on business. He told me not to look for him, saying he’d contact me himself if there was any need,’ Grandma Lyusya recalls. She had not been worried: Edik had always had a calm, independent temperament, and had never given her any cause for concern.

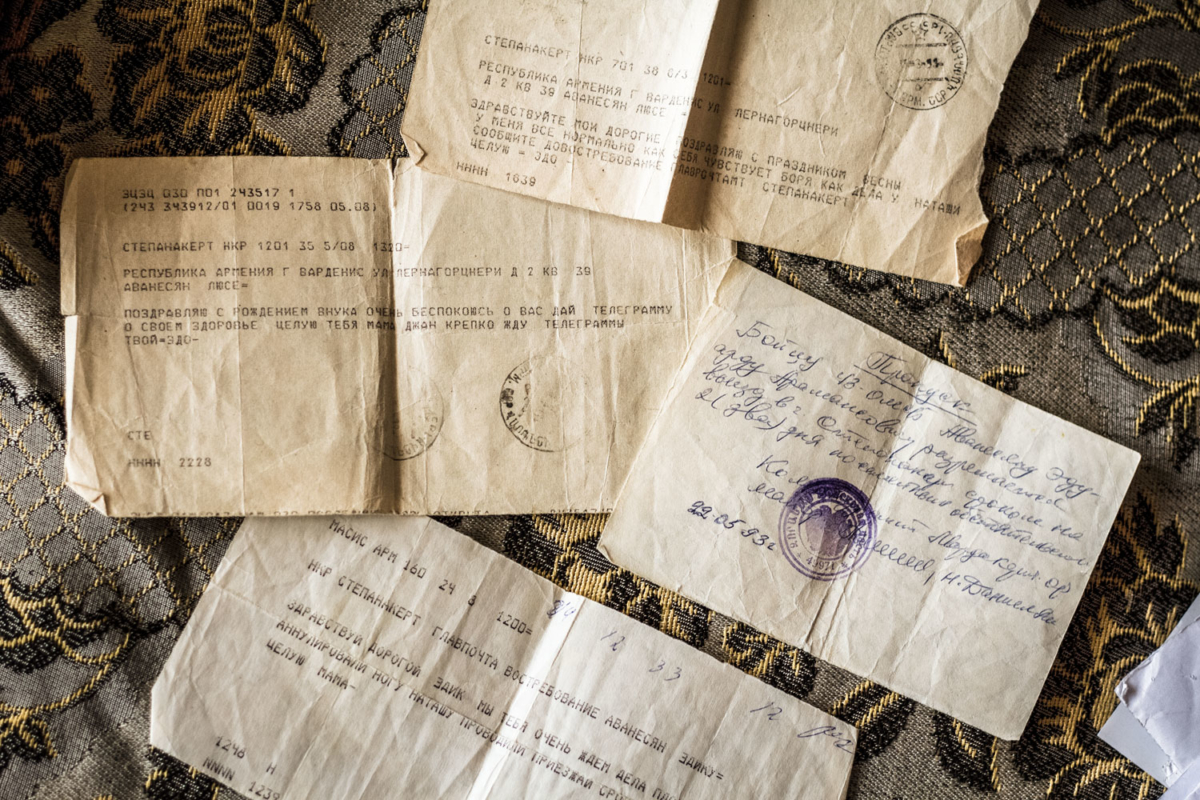

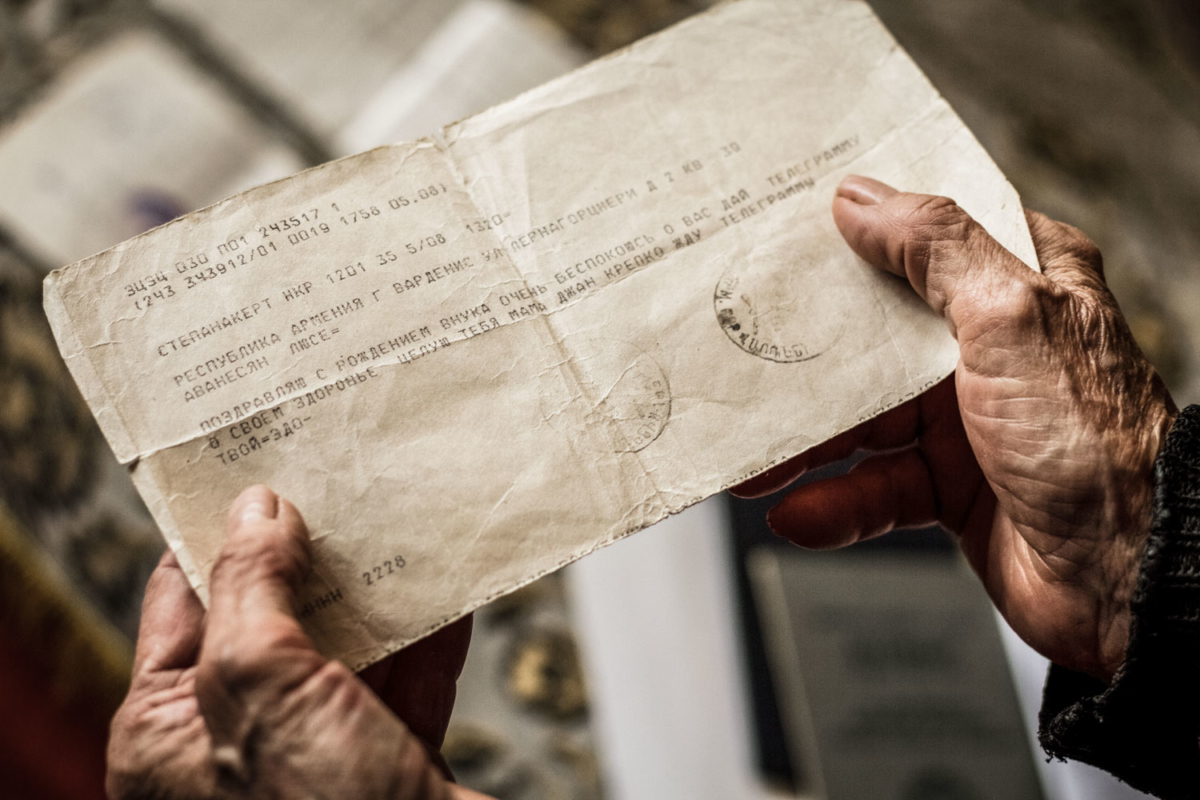

‘He would send me telegrams to let me know he was alive and well. It never occurred to me to check where they were coming from, but in fact, they were coming from [Nagorny] Karabakh.’

Grandma Lyusya admits she discovered the truth after a meeting with relatives one day. They began to ask questions about Edik, and it turned out that he and Natasha were not in Yerevan, but in Nagorny Karabakh, in Tonashen village, Martakert Province.

Throughout the entire war, telegrams were the only means of communication between mother and son. Lyusya no longer remembers how frequently she sent and received them, but she says they always helped to reassure her, making her believe that her son was well.

The telegrams, which Grandma Lyusya keeps in a special bag, provide a good record of the events that took place in the family. In one telegram, Lyusya tells Edik that his older brother had to have an amputation, and that on the day of his operation, their flat was burgled.

In one of the telegrams, Edik tells Lyusya about the birth of his son, Konstantin Eduardovich Katkov. Lyusya’s grandson is the only child of her missing son. After losing touch with him for years, Lyusya was finally able to re-establish contact.

When Natasha became pregnant in Nagorny Karabakh, her husband sent her to Vardenis to stay with his mother. After living with Lyusya for some time, her daughter-in-law moved back to her parents in Ukraine, leaving Lyusya her contact details.

Since then, Lyusya has seen her grandson twice. The first time was in 1996, when Kostya was three years old. Back then, he was living with his grandmother and grandfather, as his mother was working in a different town. Lyusya has a photograph of Kostya, which she was given at that time.

Grandma Lyusya remembers the conversations she had with her grandson, that year. One day, her daughter-in-law’s mother had advised her to make Kostya a bed up in her room, so as the boy would become attached to her. ‘I will spend time with you in the day, then go and sleep in Grandma Galya’s room in the evening,’ Kostya had said to her in response. Recalling the incident makes Grandma Lyusya smile.

At the end of her stay, Lyusya left her grandson’s family her contact details. Later, though, she lost their address, and was without any contact with them for eighteen whole years.

During that time, Lyusya kept trying to find Kostya and Natasha. She sought the help of neighbours and of her older son’s family. She trawled through social networking sites in the hope of finding her grandson and daughter-in-law, but to no avail. The way she and her family were finally reunited, however, was so poignant that, in Lyusya’s words, it deserves to be part of a book.

In 2013, a monument to those who gave their lives in the war was erected in the village of Tonashen, where Lyusya’s son Edik had fought. Lyusya was present at the statue’s unveiling.

‘Early the next morning, I received a phone call. I was a little tired when I answered the phone as I had been travelling the day before. A woman greeted me and called me Mama Lyusya. After all those years, Natasha had finally found me.’

Several months later, Grandma Lyusya went to Russia to visit her family.

‘I was standing there having just arrived, and he ran up to me and hugged and kissed me,’ Grandma Lyusya recalls with emotion. Kostya had made sure to come and meet her.

Over the next few weeks, Grandma Lyusya and her grandson and daughter-in-law were able to get to know each other better. Lyusya spent a month with them in Russia. In appearance, she says, Kostya did not resemble Edik all that much: only his eyes were his father’s. In temperament, however, he was similar to his dad: quiet, calm and steady. One day, Kostya wants to visit Nagorny Karabakh, to see where his parents used to live.

Grandma Lyusya was happy to see that Natasha had talked to Kostya about his father a great deal. Lyusya felt grateful to her daughter-in-law for bringing into the world a boy ‘with Edik’s blood flowing in his veins’.

Two years ago, Natasha remarried. Her son was against the union. ‘That’s his Armenian blood,’ Grandma Lyusya remarks, half-joking.

These days, she speaks to them on the phone.

Although she has not heard from him for twenty five years, Lyusya is still certain that one day, her son will return.

When the war ended, in 1995 Lyusya had gone in search of her son, making the journey to Shushi.

‘I went to every single village, holding a photograph of my son in my hands. I spent four or five days looking for him. In those days, the armoured vehicles were going to and fro all the time, so I never had to wait around. They’d always give me a lift to the next village, then go off on their way,’ Lyusya recalls.

All Lyusya was able to find during her travels, however, was her son’s army hat. The

eighty-one-year-old woman keeps it still, and has never washed it. It is one of

the very few things of Edouard’s that she has.

Her neighbours say Lyusya will always raise a glass to her son’s health on New Year’s Eve and other special occasions. She has not put up a candle in front of his photograph, and always celebrates his birthday with the neighbours.

‘Whether they come or not, I always cook a special meal that day. I wouldn’t say I produce a huge spread, but even if I have to save up all week, I always make sure to mark his birthday.’