Last week before the election in Abkhazia

Abkhazia is going to elect a new parliament on Sunday, March 12. This will, probably, be the last ballot, in which the republic will elect country’s main legislative body through the majoritarian vote system.

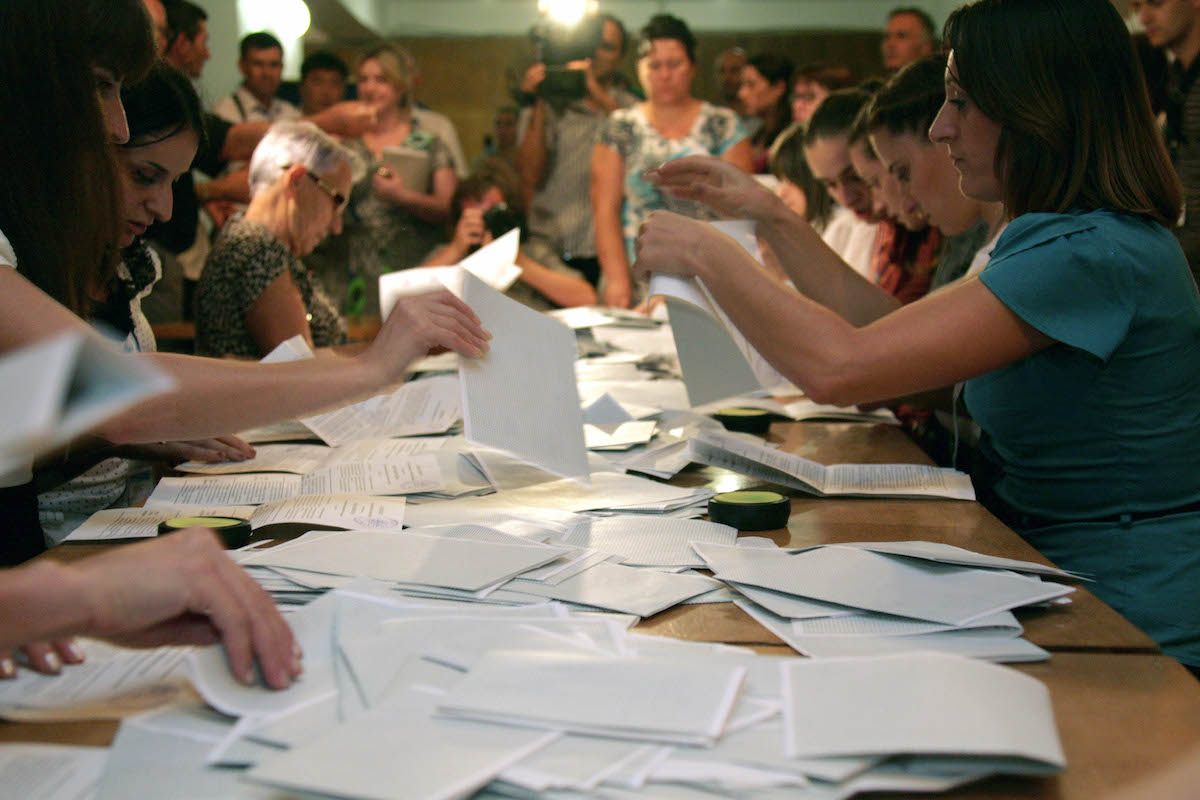

photo: Ibragim Chkadua

Either to have a road repaired or to have kin. But it’s better to have both

There are 138 candidates running for 35 seats in the People’s Assembly. However, at least one- third of them refused to take part in direct debates, organized by the national television and the private Abaza TV channel. And that’s despite the fact that the air time for MP candidates is free.

The main reason for ignoring such campaign format is actually very simple. The ‘objectors’ realize that participation in debates without possessing any particular oratory talents could be only disadvantageous.

Thus, the preference is given to more common mechanisms of influencing the electoral environment-i.e. addressing particular district’s social problems.

At the same time, this form of attracting votes, when MP candidate actually performs a foreman’s duties to citizens free of charge, is widely applied not only by the ‘objectors’, but also by those candidates who never miss TV air. As a result, one has a feeling that the maintenance and cleaning months has been announced throughout Abkhazia.

Roads and bridges are being patched, water supply systems are being laid, transformers are being installed, children’s and sports grounds are being arranged everywhere. And this is done not only through the budget funds.

Unlike the urban districts, where candidates who don’t resort to voter bribery stand at least some chance to be elected at the expense of their program, charisma and oratorical skills, a ‘something for something’ principle works almost without fail in the regions. Not a single program and eloquence is capable of bringing as many votes to a candidate as the lighting system installed on the rural road on his behalf.

‘Crony’ mindset is another efficient mechanism. It implies that a voter casts ballot exclusively for his/her next of kin, probably even remote, but still, a relative.

Therefore, the chances to win the election even for Aslan Bzhania, the opposition leader who, on a side note, gained 35% of votes in the last presidential election, seem to be rather vague. Bzhania stands for Atar constituency, where his key rival is Temur Kvitsinia, a representative of one the most influential and numerous Abkhazian families.

Representatives of the Kvitsinia clan make up almost half of the voters in this constituency. And, as a rule, all of them amicably vote for their relative. Temur Kvitsinia, who, by the way, is said to be the most silent MP, certainly would have had no chances to be elected in any other constituency. But his rate is almost unbeatable in Atar constituency. He won parliamentary elections there twice in succession, confining himself exclusively to the first round, which seems to be a fantastic result for the present-day Abkhazian realities.

Those two negative factors – voter bribing and cronyism, that are characteristic of the majoritarian approach on a large scale, have actually become the main reason for the upcoming reform.

Abkhazian Parliament already considered in the second reading the constitutional bill on transition to a mixed proportional-majoritarian electoral system. Initially, it had been planned to shift onto this system by this election. However, after the lawmakers failed to reach consensus on the number of MP seats in the new Parliament, the issue was dragged on. So, it will be the new composition of the People’s Assembly that will pass the bill in the final reading.

However, the fact that this election is the last one held through the majoritarian system is hardly what it will be best remembered for.

Ex-President Alexander Ankvab’s participation in this election is probably the most intriguing factor of this campaign.

Ankvab’s factor

Alexander Ankvab was nominated by various initiative groups for 3 different constituencies at once. In addition, nearly all opposition organizations, as well as separate groups of intelligentsia and mothers, whose sons perished in the Georgian-Abkhazian war, appealed to Alexander Ankvab, who has been living in Moscow for the past 2,5 years (since his early resignation), requesting him to return to active political life and run for parliament.

Finally, Ankvab returned and nominated himself as an MP candidate for Gudauta city.

His return caused serious public outcry. It turned out that there were quite a lot of active opponents, who objected ex-president’s return to politics. War veterans held a protest rally at Gumista Bridge, where there was a front line during the Georgian-Abkhazian war, demanding from Alexander Ankvab to quit the election race, since, as they believe, ex-president’s return to politics is the key destabilizing factor.

The ‘hero of the occasion’ himself hasn’t given up on the idea of becoming an MP, though he actually has reduced his campaign efforts down to zero. He doesn’t go to the meetings with the electorate, doesn’t declare his campaign program, doesn’t apply to visual agitation and doesn’t make appearances on TV.

Ankvab didn’t even show up in the CEC to get his MP candidate’s ID. It was the ex-president’s relative who came to the CEC to receive the document based on the notarized power of attorney.

Inal Khashig’s review on major political developments in Abkhazia in 2016-much information that gives context to the ongoing political battles and changes.

A protester shouts during a rally against planned increases to the nationwide pension age in Moscow