In the camp: After the war

The eyes of 15-year-old Eric clearly reflect all the grief which has accumulated there in the recent years. The memories of the hostilities in his native village are still fresh in his mind. He can hardly hide an irresistible desire to return to Talish, where he spent his childhood and where he still sees his future.

“Shooting had been always commonplace in our village and we are no longer afraid. But it was really awful that day. We were woken up by the sounds of shots, went down into the basement and stayed there until 3 a.m. Then we came out and went to the village administration building. Villagers were evacuated in cars from there. When in the basement, I thought it was the end…but if we can be sure about our safety, we will be the first to return to the village, says Eric Sargsyan.

He is from the Talish village, located in the southeastern part of Nagorno-Karabakh. His family now lives in Charentsavan, Armenia.

Talish residents (500 people) were evacuated following large-scale hostilities waged by Azerbaijani armed forces on April 2nd of this year. They resettled in various cities of Karabakh and Armenia.

David Petrosyan, 14, is also from Talish. Like many others, his family was also taken to Charentsavan. The only thing he remembers from the April 2 nightmare is how hard he pressed his hands over his ears to muffle the ‘sounds of war’.

“I had many friends there, but now we’re all in different places: Charentsavan, Hrazdan, Abovyan…We miss each other, but iwhat can we do? That night I was sure everything would be fine, that we would survive. Now we are here, making new friends. Everybody here has gone through the war, and that’s exactly the thing that unites us somehow, says David, tightly hugging his brother Vahe.

8 teens from Talish spent the last days of summer together with other 32 youngsters, who had earlier moved to Armenia from from Iraq and Syria, in the Aramyan camp of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), in Vanadzor, 150 km away from Yerevan.

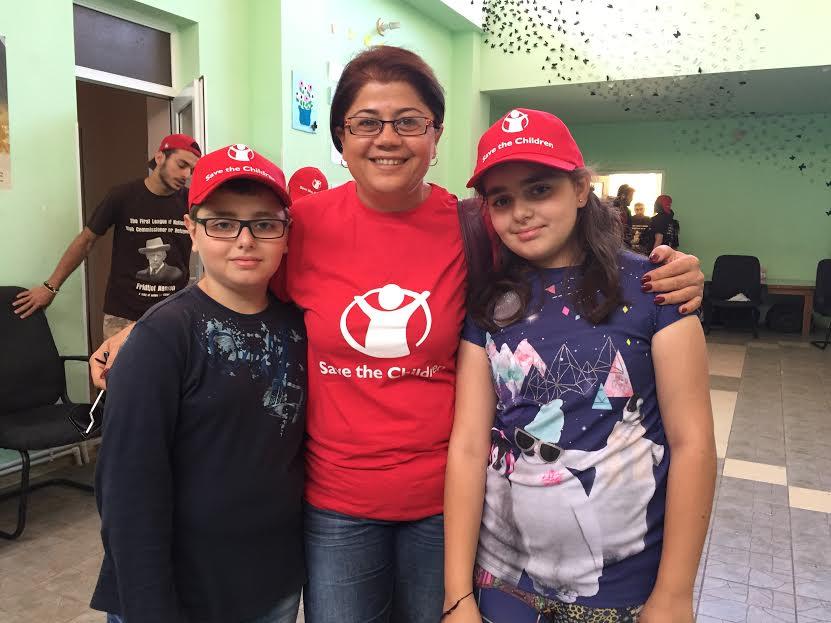

According to Siranush Vardanyan, the head of the program Save the Children, which assists Syrian Armenians and is a project that is underway in the Aramyan camp has a single goal: to relieve the children’s stress, who, at various points in their life, have experienced the horrors of war. In his words, the YMCA camp provides the best conditions for acheiving this goal. It has become possible to implement the program through funding provided by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

“Regrettably, these children and young people have experienced war. They have seen mines and bombs explode right in front of their eyes. They witnessed all these things, and here they trying to get rid of their stress. Our volunteer youth leaders are Armenians from Iraq and Syria, who themselves immigrated to Armenia not too long ago. They have gone down the same road as these children, who are a little bit younger than they are, are taking now, says Siranush Vardanyan.

Each of the youth leaders has 4 supervisors. The camp participants’ ages ranges from 12 to 17. They spend 12 days total in the camp. There is no Internet in the YMCA Aramyan camp and the children don’t use mobile phones either. It’s not something random nor something created to realize the project, but rather an individual approach in the psychological rehabilitation process.

Anahit Hayrapetyan, External Relations Coordinator at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR Armenia), notes:

“Eeveryone here has his/her own role and responsibility. You can hear Western Armenian [spoken by non-native Armenians], as well as the Eastern Armenian [which is spoken in Armenia]. There are youngsters in this group, who have just recently moved to Armenia. There are also those, who’ve been here for quite a long time already. All of them have their wounds to their souls: some of them have deeper ones, others’ have more or less healed, some of them have already been to this camp and everyone understand each other, says Hayrapetyan.

Nanor Abelyan, 14, moved to Armenia from Aleppo two years ago. She admits that she doesn’t want to return home. It seems to her as if people in the camp have known each other for a long time:

“I don’t feel any difference between us. The only thing is that the Armenians from Talish speak slightly differently. We are all Armenians. What unites us is that all of us have experienced war- the Iraqi Armenians went through it a little bit earlier, then we did and now Talish natives. However, we don’t talk about that here. It’s like a dream for me. And this is our homeland.

Youth leaders work with groups in the daytime: some of them dance or sing, other groups hold discussions about friendship, peace and integrity, while others get familiar with the fundamentals of leadership.

Shant Sargis Avadis, 20, moved to Armenia from Iraq a decade ago. He is one of the volunteers at the Office of UN High Commissioner for Refugees. In each Talish teenager he could recognize himself 10 years ago:

“We’ve gone through it ourselves and now we are trying to shake those memories out of these youngsters. I could see a part of me in their eyes. What I had to witness was unimaginable: exploding cars; human heads and legs flying in the air…My mother was killed there. I came to Armenia together with my father and my sister. It’s a great responsibility for us, the leaders. What the camp gives us are new friends, new people with their own stories and a new character.

The camp is secludedly hidden in dense forests, typical in the Lori region. The days begin with observing the sunrise and end with conversations around campfires.

Nubar Nalbandian, 20, a youth leader, is also from Aleppo: “At night we have a talk like being with a psychologist about trust and responsibility. We listen to their opinions. We don’t talk about the war, but we work towards helping them overcome their stress post-war.

Mariam Sargsyan, a consulting psychologist at the UN Children’s Fund, also works with these young people. She notes that the children from Talish are still experiencing post-war trauma. The Syrian youth, who have been living in Yerevan for several years, already have some sense of security, but they, in turn, have been facing some other challenges, commonly referred to as post-migration adaptation problems.

“The Iraqi youth are already mature and they are here in the capacity of the youth leaders. It is remarkable that they have assumed a role that implies with a great responsibility at this stage in their lives. When you are responsible for helping others, the inner gears start working harder, which is a perfect opportunity for them to test the limits of their capacity and unlock their potential. They are youth leaders, who can become an ideal model for the younger ones, says the psychologist.

Even the cuisine here has been well thought-out in order to make everyone enjoy it. Karine Boyadjan, the camp director, says the menu has been created so as to make everyone happy:

“I was a little bit worried about those from Talish. I thought they might not like the food, but I could say that Syrian cuisine has caught everybody’s fancy.

The program officials believe that the existing cultural differences will be beneficial for everyone.

Mariam Sargsyan, a psychologist, notes: all of them could feel that they went through the same thing, have experienced the same shock, and some of them have already overcome all their troubles:

“They can already make certain conclusions with regard to their lives; they are inspired to create their own vision of the future. And the more diverse the visions of their futures are, the more alternatives there will have, the more flexible they will become and they will be able to become adapted much easier. In this regard, sharing their experiences will have a positive effect on them.

The opinions expressed in the article convey the author’s terminology and views and do not necessarily reflect the position of the editorial staff.

Published: 02.09.2016