Guests in their own homeland

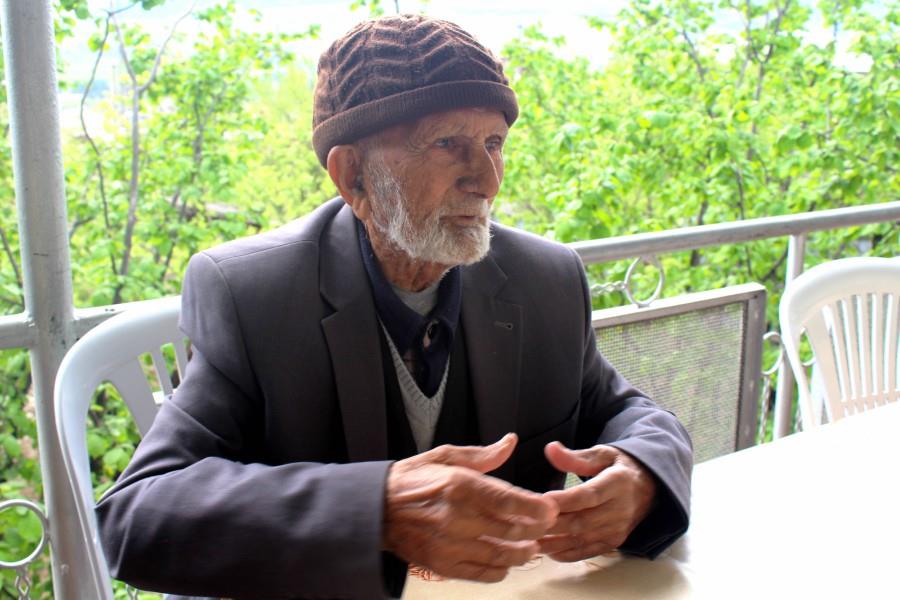

Seyfat Dursunov is 91. He complains of old age and can hardly recall what happened yesterday, but still there are certain things that his memory has preserved almost intact.

‘It was November. It was snowing heavily that year. Big trucks drove into our village, Utkisubani, late at night. We were forced out into the street, seated in the vehicles and taken to Akhaltsikhe. A freight train was waiting for us there. We travelled for 40 days. It was chilly. We had no food. I was 20 then, and I parted from my homeland for nearly my whole lifetime,’ he recalls.

Sayfat Dursunov

Seyfat Dursunov was one of the 120,000 Muslim Meskhetians, who, on Stalin’s order, was exiled from Meskhetia to Siberia and Central Asia one November night in 1944. Many did not survive this hard and lengthy journey – several thousands died on the way. The reason they were exiled from Georgia was Stalin’s suspicions that Muslim Meskhetians might oppose the Soviet army was in case of the enemy’s invasion.

In the late ’50s, after Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union launched a process of rehabilitation and repatriation of those persecuted by the ‘Great Leader.’ However, that did not apply to Muslim Meskhetians.

In the 80s, they became victims of persecution for the second time, turning into a target of ethnic violence in Central Asia. They found refuge in Azerbaijan and the southern regions of Russia.

At present, this persecuted community is scattered around various post-soviet countries. Some of them have managed to emigrate to the United States, while others have returned to Georgia.

In 1999, when Georgia joined the Council of Europe, Tbilisi took an oath to repatriate Muslim Meskhetians and some concrete steps were taken towards reaching this goal – Georgia passed a repatriation law in 2007.

Almost 10 years have passed since its adoption and everything seems to be in order at the legislative level. However, despite all this, the Muslim Meskhetians, who reside in Georgia, still don’t have reintegration status. Even fewer of them have managed to acquire citizenship. Some reprimands have been voiced from those above – speaking at the April plenary session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), now-former Prime Minister of Turkey, Ahmet Davutoğlu, reminded the Georgian authorities of their commitments with respect to Muslim Meskhetians.

‘We hope that the repatriation of these people will be one of the priorities of the Action Plan of Georgia, a member of the Council of Europe,’ he said.

Tbilisi is bewildered by Davutoğlu’s statement. ‘Doesn’t the Turkish Prime Minister really know that Georgia has fulfilled with its commitments?’ wonders Zviad Kvachantiradze, a leader of the parliamentary majority group.

The opposition members are echoing the same.

‘Everyone willing to return to Georgia has been given a chance to register. Moreover, the registration deadline has been extended twice, says David Bakradze, a leader of the United National Movement.

Human rights activists and representatives of NGOs, dealing with the Muslim Meskhetians’ issues, do not deny the fulfillment of the commitments either. However, the lengthy procedures for obtaining reintegration status, as well as the being denied citizenship and tough social conditions, make the Muslim Meskhetians’ life in Georgia even more unbearable – they say.

Official statistical data is as follows: 5,841 individuals applied to Georgia for reintegration status over the past few years. 1,533 of the aforesaid number have been granted this status and 494 people have received ‘conditional citizenship’ that implies that Georgian citizenship will take its effect immediately after they renounce the citizenship of another country. As officials explain, people are usually refused to be granted this status and citizenship due to inproper documentation.

And in the meantime, time goes by. Returnee Muslim Meskhetians cannot resolve their elementary daily problems, not to mention their integration into the society.

Being stateless, they are not entitled to buy agricultural land; they cannot benefit from social programs and are facing obstacles in public educational institutions.

The vast majority of Muslim Meskhetians don’t know the Georgian language and are unfamiliar with Georgian legislation. This further complicates their daily life, making them face a lot of bureaucratic challenges in relation to the local government.

‘They haven’t stalled our return, but they are creating all the conditions they can to make our life here unbearable,’ says Seyfat Dursunov, recalling a tragic story that happened 70 years ago. It has been 8 years since he returned to Georgia from Azerbaijan.

None of Seyfat’s family members have Georgian citizenship or reintegration status. His two sons, who having failed to find any work in Georgia, left their elderly father and went to Turkey for work. Seyfat now lives with his 23-year-old granddaughter, who takes care of him.

There are about 50 Muslim Meskhetian families in Samtskhe-Javakheti. 20 of those families live in close quarters at the Akhaltsikhe freight station. The rest of the families reside in Vale, Adigeni and Abastumani.

Muslim Meskhetians residing at the freight station

Most of them returned to Georgia in 2007-2010. They purchased houses with their own finances. They earn living through agriculture – cultivating fruits and vegetables on a small piece of land around the house.

‘We do not have any status; there are neither jobs nor prospects for us. We live in our motherland, but we are nobodies,’ says Bakhtiyar Azizov, 43, who lives at the Akhaltsikhe freight station together with his six-member family. He is stateless. He was refused to be granted reintegration status, as well. As he says, the reasons why were not explained to him.

Bakhtiyar’s dream is to have a plot of land where he can grow crops and put his family back on its feet.

His neighbor, Yusuf Suleymanov, 45, has been repatriated. However, he says, ‘this certificate is just a blank piece of paper and is of no benefit for him.’ He has built a greenhouse in a small yard outside the house, where he grows cucumbers and tomatoes and thus provides for his family. Being a stateless person, he is not entitled to purchase agricultural land.

The Suleymanov family greenhouse

‘If I had a piece of land, I would work a lot. The matter is not that you just return…we do not know the language and we are unaware of the rules and the law. Someone should pay attention to us, tell us how and what to do…’ says Yusuf and shares his story: he recently put a roof on his house, but as he was unaware of the local laws, he did not apply for permission. Now, Akhaltsikhe City Hall is lodging claims against him because of illegal construction – if he does not submit the proper documents in two weeks’ time, he will have to pay a 3,000 GEL fine. It’s a tremendous sum for Suleymanov’s five-member family, in which no one is employed.

Tazagul Fazliyeva. In Tazagul Fazliyeva’s words, she is not allowed to build a house

Among the freight station dwellers we also met some with Georgian citizenship. ‘Once you have Georgian citizenship, Georgia seems to be your home and you no longer feel like a guest here. I work and live well,’ says Tursun Temiyev, proudly demonstrating his passport.

Tursun Tamiyev says, after being granted Georgian citizenship he has no longer had any problems

According to Tsira Meskhishvili, the head of the Tolerance organization, who has been dealing with Muslim Meskhetians’ problems for years, the country does not do anything to help them integrate.

“The authorities are right, when they say that all commitments have been fulfilled from a legal point of view. However, there are also moral and social commitments. Those who return here should have a decent life, shouldn’t they? The law does not provide for that, and the state does not do anything either. If they were to have citizenship, they would tackle many problems themselves,’ says Meskhishvili.

The Georgian Public Defender’s 2015 report on the situation then in the human rights sphere also points to the fact that Meskhetians’ integration relies on government’s support:

‘The law just defines the procedure to be considered as repatriated. It does not provide for any socio-economic guarantees and property-related issues.’

According to the report, those repatriated with no Georgian citizenship are facing problems with education, health and employment.

Government officials do not deny the existence of those problems either. However, in their words, integration is just a goodwill rather than the state’s obligation.

‘Georgia’s commitment was to create a legal framework for repatriation, and it has done it in good faith. As for integration, it’s our goodwill. The work on integration action plan has been already finished and has been submitted to the Council of Europe. As soon as we get a response, we will immediately start its implementation,’ says Irakli Kokaia, the Head of the Department for Repatriation and Refugee Issues.

In his words, the country cannot afford to undertake any moral obligations. ‘With our desire to provide everyone with a house over their heads, we do not have such an opportunity. A country with over 50,000 refugees cannot keep such a commitment. These people were exiled from Georgia by the Soviet Union, and it’s successor now is Russia. So, the burden now lays on Russia to fulfill this moral commitment, says Kokaia.

Nevertheless, Muslim Meskhetians also see certain positive trends in living in Georgia.

Many years ago, when they started returning to their homeland, there were frequent media reports on confrontations between Meskhetians and the local population, as well as conflicts between Christians and Muslims. Such reports have become a rarity nowadays.

‘We have found a common language. People have accepted us, but the state has not, says Seyfat Dursunov.

The freight station residents also can confirm that. Ramin Fazliyev, a Meskhetian, says he can always rely on his neighbors:

‘If I need a car, I go and tell my neighbor – give me the keys, and he gives them to me. He is a Christian and I am a Muslim …so what?’

Faya Gokharova and her Christian neighbor

Mzia Merabishvili, a local Christian, speaks about her the neighborly relations with Muslims

Ramin’s mother believes, the government is deliberately posing problems to Muslim Meskhetians to urge them leave the country:

‘If they don’t need us, they should just tell us. Let them buy our houses, give us compensation and we will leave,’ says Tazagul Fazlieva.

Published:12.05.2016