Children playing funeral: Gagauz traditions in Moldova

Funeral traditions in Moldova

Text by Alina Mikhalkina

Illustrations by Tatiana Bulgak

For the Gagauz people, a Turkic-speaking ethnic group who follow the Orthodox faith, funerals are among the most important events. For centuries, elderly individuals have been preparing for their departure in advance: buying necessary items for the funeral ritual.

Partnering with JAMnews, the Moldovan media outlet NewsMaker decided to explore how this knowledge is passed down in Gagauz families from generation to generation along the female line, through the stories of two residents of Chadyr-Lunga: 83-year-old Matryona and 88-year-old Zinovia.

Matrena Lazareva will turn 84 this year. She greets us at the doorstep leaning on a cane, wearing a housecoat — one of those worn for guests’ arrival. Our heroine was born in the village of Alexandrovka, Bolgrad district of the Odessa region — one of the oldest Gagauz villages in Bessarabia. The first Gagauz families settled there at the end of the 18th century.

“I was born on April 1, 1940. My very first funeral was my father’s; I was four years old at the time. He fell ill with typhus and passed away in 1944 in the hospital. His body was washed there, my uçu (uncle in Gagauz) — his brother washed him, dressed him, placed him in the coffin, and he was taken by hearse to the cemetery. I remember the hearse passing by our house, but they weren’t allowed to bring him home; no one [who died of typhus] was allowed to be brought home. Those were my first funerals,” recalls Matrena.

“Making dolls that lived, then died, and then they were buried”

Not so far from Aunt Matrena, on the street named after Karl Marx that has remained unchanged since Soviet times, lives another long-living resident of Chadyr-Lunga — Zinovia Stamova, Aunt Zina.

Aunt Zina is 89 years old, leans on a cane, but her smile hasn’t changed over the years — just look at a photograph of her in her twenties.

Aunt Zina leads us into the room, we sit down, and she begins her story right from her childhood, which fell on the interwar period.

Back then, she and her cousin Fanya “played funerals”: the girls wrapped corn cobs in rags, buried these “deceased” at the edge of the garden, and lamented over their “graves.” This was their imitation of adults — funerals in Gagauzia always drew large family gatherings.

“There were no dolls, nothing. We made dolls ourselves; they lived, then died, and then they were buried,” recalls Zinovia of the hungry 1950s of her childhood.

The children witnessed numerous burials. Growing up and inheriting traditions from her mother, Zinovia herself organized dozens of real funerals — following all the rules.

Now Zinovia lives alone in her house in Chadyr-Lunga. Her daughter Sonia and son Vanya live separately from their mother. The head of the family passed away 27 years ago. Aunt Zina is preparing for her own funeral and passing on Gagauz traditions further.

She says that traditions have always been passed down through the female line — from mother to daughter. “I was 26 when my mother passed away. But my mother often talked about [funerals].”

Now Zinovia herself advises women in the neighbourhood and relatives on how to properly bid farewell to the deceased. The woman’s house stands not far from both cemeteries of Chadyr-Lunga. Her loved ones are buried in both of them.

“Where do I know it all from? My grandmother told me, my mother’s mother”

About 60 years ago, Matrena’s grandmother, Elena, or Babu Lianka as she was known in the village of Alexandrovka, told her about burying the deceased and preparing for funerals rules.

‘How do I know it all? My grandmother told me, my mother’s mother. I was in my early twenties, my grandmother lived for a long time, but she fell ill towards the end of her life. She saw that no one wanted to wash her, but a sick woman needed to be washed, and I wasn’t afraid. And when a person dies, they need to be washed too, and it’s important to have someone who isn’t afraid nearby. That’s what my grandmother explained to me. I wrote everything down and set it aside. My grandmother chose me because I was lively, daring, and not afraid of anything. Since childhood, I could go into a dark room, but my brother wouldn’t go in there for anything,’ she explains.

“Who comes to wash the deceased? Those who aren’t afraid”

She says that not everyone is willing to wash the deceased. ‘Who comes to wash the deceased? Those who aren’t afraid. Personally, I wasn’t afraid, and wherever I was called, I always went. I washed my mother-in-law alone, her four daughters didn’t even come close,’ Matrena recalls.

She explains that among the Gagauz, it’s customary to cover the deceased with a cloth after death and leave them for a couple of hours until the body cools down. Then they can proceed with washing: usually, men wash other men, and women wash women.

Aunt Matrena washed almost all the deceased women in her ‘mahala’—two small streets in the center of Chadyr-Lunga.

‘If someone passes away, they come and say: “Passed away, come to wash.”‘ Wash with warm water, without soap. The body must be washed thoroughly, not just for show, because as we send them off on the final journey — there, in front of the angels, a person must be clean,’ says Matrena.

She says that she instructed all her helpers on where and how to wash the deceased: ‘If it’s warm, they wash outside, and the water should flow down the path into the garden.’

But lately, Aunt Matrena says, more and more deceased are being taken to the morgue to be washed: ‘Now, in the city, they rarely wash the deceased at home. Mostly they’re taken to the morgue, where there’s a woman who handles everything alone, washes, dresses. They might even put the deceased in a coffin at the morgue and bring them home. Maybe it’s for the best, because there’s less distress.’

“Nowadays, it’s different. We live differently, and we die differently”

Zinovia often reminisces about how things were before. And although the Gagauz people try to preserve the spirit of tradition, much is changing. Nowadays, many rent separate halls for the deceased, buy coffins instead of making them themselves, and increasingly entrust the washing of the deceased to morgues.

“Before, even digging the grave was done by our own people. Relatives would go and dig. And as for the coffin – we used to buy logs, make it ourselves, and keep it in the attic. Let it wait. But now, funeral bureaus… They order the coffin from them, and let them dig the grave too…”

– Which do you think is better? The way things are now or how they used to be?

– How it used to be was better.

– Why?

– Our own people did everything. But now it’s different. We live differently, and we die differently.

“I didn’t want to bury him in the suit he wore to school”

After washing, explains Aunt Matrena, they dress the deceased. And there are rules for this too.

“For a woman, they first put on an undergarment: if there’s a shirt from her wedding, they use that, otherwise just a regular one. All the clothes are prepared in advance. But when my daughter Zinochka passed away, I had nothing. I remember, I went to the hospital, and the doctor told me she didn’t have long left, just a little while to suffer. I only asked what dress I should put on her. ‘Only white, because she’s leaving as a girl,’ that’s what he told me,” Aunt Matrena recounts.

She buried two of her children: first her sixteen-year-old daughter Zina, and then a couple of years later her son Kolya died in an accident. He was 12 years old.

“His father carried him to the hospital and cried. Then he recalled, when he stopped and looked up, there were people in every window. Since Kolya died suddenly, what could I dress him in? I went to the store and bought a suit, because I didn’t want to bury him in the suit he wore to school — I wouldn’t see him in it anymore,” the woman says, and we all fall silent.

“When you come to pick up the dress, you’ll see everything”

Aunt Matrena breaks the silence herself. She starts the conversation right where we left off: with the tradition of dressing the deceased among the Gagauz.

“How to dress them? We dress them in everything new, not in anything worn. A ‘yüklük’ is to be prepared — a cover, bedding, a rug — all of this is given to an orphan or an unmarried girl after the funeral, so she remembers the deceased when she uses it. Everything is ready for me; let me show you,” Matrena invites us into the largest room of the house — the hall.

Following her, we, two correspondents, and Aunt Matrena’s granddaughter Zinochka, walk into the unheated hall. Here, when the time comes, the ritual of her funeral will take place, explains the woman. But for now, neatly hanging in the wooden wardrobe are a woolen sweater, a skirt, and at the bottom are shoes a couple of sizes larger.

“Here’s everything necessary: a ladle for pouring water over the body, a towel for drying. The towel will be placed under the pillow in the coffin, and I’ll be buried with it. I showed all of this to our neighbor; let Zina see it too. I’ve prepared everything for what needs to be laid in the coffin, who gets what; you’ll see it all when you come to pick up the dress. It’ll be easy to bury me; I’ve prepared everything,” our heroine addresses her granddaughter.

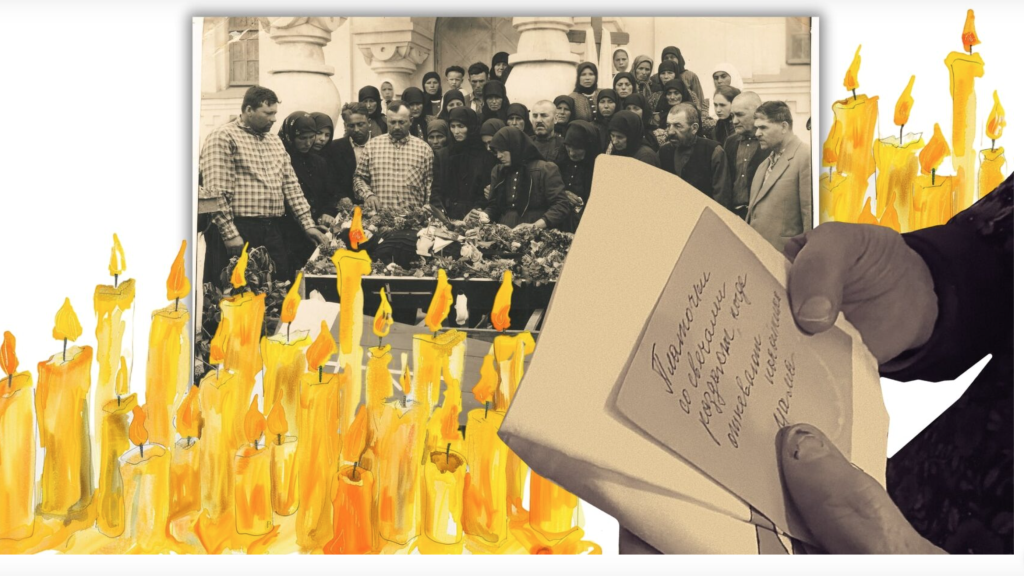

“Handkerchiefs with candles are handed out when mourning the deceased. Mom”

Then Matrena goes to a large cardboard TV box: it contains everything that will be needed for the funeral later: handkerchiefs for candles, towels for the priest who will come to perform the funeral service, shirts for the men who will carry the coffin, and even fabric ribbons that the men will tie around their arms – they are called “mezarcılar”.

Everything is neatly arranged in packets and small bags, with a note from Aunt Matrena in each of them. “Handkerchiefs with candles are handed out when they are mourning the deceased. Mom,” is written on one of them.

“Next to the deceased walks the Jadu grandmother” and other Gagauz beliefs

In Gagauzia, it is customary to bury the deceased on the third day after death, and until then, the deceased is not left alone at night.

“During these three days, the deceased should not be left alone, and a lamp must always be lit in the room. In the evening, someone must be found to keep the deceased company. Gagauz people believe that a ‘Jadu’ grandmother (a sorceress) walks beside the deceased and gathers threads tied to the deceased’s legs. God forbid you oversleep, as someone might steal the rope, and with it, they can commit evil deeds,” explains Ludmila Marin, director of the National Gagauz Historical and Ethnographic Museum named after Dmitry Karachoban in the village of Beshalma.

Usually, while the deceased’s body is still at home, relatives and acquaintances come to pay their respects and bid farewell. They bring bouquets of flowers with a request for the deceased to pass their greetings to their deceased relatives in the afterlife. “The bouquet must be tied, otherwise, it will scatter, and the soul of the deceased will not know who the flowers are for.”

The deceased is mourned at home on the third day, after which the funeral procession heads to the cemetery. It is led by a person carrying a bucket of water.

“They stop at every crossroads and pour out a little water. This is how people give the most precious thing—water. The thing is, Budzhak is a steppe with little precipitation and frequent droughts, so some funeral rites and customs are associated with water. For example, there is also the ritual washing of hands before sitting down at the memorial table,” explains the director of the Beshalma museum.

She also mentioned that in Gagauz settlements, it is customary to carry a branch of a fruit tree, called “dal,” during funerals, on which bread kalaches are hung. These are taken off the branch at the cemetery, the kalaches are broken into pieces, and distributed to those present, accompanied by a glass of wine—like if it was a communion.

Overall, Gagauz funeral traditions are closely intertwined with religion. “All life, all traditions are linked to religion, to the Christian faith, and this is still preserved to varying degrees today,” says Ludmila Marin.

“The funeral instructions” and the desire to “ease the future of the departed soul”

After the funeral, Gagauz people continue to honor the memory of the deceased: on the ninth and fortieth day, when, according to beliefs, the soul has not yet been determined to heaven or hell, Gagauz people invite the deceased’s closest and dearest ones, as well as those who washed the deceased and carried the coffin, for a meal. They also go to the cemetery for memorial services and bring kutia (sweet grain pudding), kalaches, and wine to the grave, all blessed in the church.

Here, at the Beshalma Museum, we were shown a book by Hieromonk Ioann Peioglo from Comrat: it contains photographs of a diary by a parishioner named Dyulger from the village of Beshalma. In 1953, she compiled a peculiar illustrated guide for conducting funerals and called it “Yolyullar ichin” — “About Funerals.” As the museum staff explained, the original diary is lost.

“She describes what is needed for male and female funerals, how much money is given to the priest and his assistant (the deacon or the sexton). ‘The priest receives ten rubles,'” the guide says. She also drew a fruit tree that is carried to the cemetery and a traditional table — a sofra, which is given to one of the relatives for forty days.

“Funeral and post-funeral rituals are among the most significant rituals not only for the Gagauz people but also for others, because this is our memory. With the departure of a person, a part of life goes away, memories remain,” says Lyudmila Marin. “Losing someone, we want to observe traditions. Perhaps in life, we deprived or offended him in some way. And we also hope that this way we will ease the path of the departed soul.”

Matrena and Zinochka escorted us to the doorstep. Aunt Matrena lamented her age, saying that she wouldn’t go any further – it’s hard to go downhill.

“Now I’ve grown old,” the heroine says. But at 84 years old, Matrena Pantelievna, just like in her childhood, isn’t afraid of “dark” rooms: ten years ago, she prepared everything for her funeral and left instructions on small pieces of paper. Now she’s calm: when the time comes, her granddaughter will know how to send her off according to Gagauz customs and traditions.