Armenia's children with disabilities often abandoned, rarely adopted

“I gave up my child…”

“The first thing I remember after giving birth is that the doctor asked: ‘Have you had your tests done?’ Instead of giving me my child, they took me to another ward. I didn’t understand what was happening, and thought that the world around me would collapse.”

It was only a few hours after her son’s birth that Anna (name changed) was told – or rather, informed, as if she was being sentenced – that her child had a disability. Nobody openly said ‘give the child up for adoption’, they simply said they regretted that she would have to spend her youth and energy on a ‘sick child’, and that he would ‘definitely have heart problems, a weak constitution and mental retardation’. They predicted that after the birth of the child her family would fall apart.

They made it sound as if Anna’s life was over.

“After birth, almost all women experience depression. That is normal. In this situation all the comments were simply unbearable. It seemed as if a funeral procession had come to visit me. The only solution was to give the child up. I was afraid because I didn’t know how to live going forward. The only thing of which I was sure was that I wanted the story to be over as quickly as possible. I wanted for someone else to take responsibility. I didn’t have the strength to go forward,” says Anna.

• What’s better – being a parent to a son or daughter?

• 14 kids in a family – a video story from Armenia

• Inclusive education in Armenia – an opportunity for children and corrupt officials

Anna’s story became public knowledge, and people talked about her and hated her.

“I could never imagine that people can contain so much hatred. Never. I received letters from people cursing me. It seemed that the only aim of those people were to destroy me. Everyone judged me as if they were God. Nobody understood that I am first of all a human being too, then an Armenian, and also a woman. I have my own fears, doubts and weaknesses. It was as if I was the first mother to give up her child,” she recounts.

Not the first, not the last – statistics

There are 638 children in Armenian orphanages, of which 471 have disabilities.

Over the past two years, 130 children have returned to their biological homes from orphanages. Nine of them have special needs. In the same period 105 children were adopted, of which 15 had disabilities.

Seeing with the heart: Hovhannes

“I knew that she would be my mother. When she hugged me for the first time in the orphanage and said ‘My love!’ I immediately understood that she’s my mother,” said Hovhannes.

Anahit shyly smiles – she acts this way with all the children. She is happy – through God’s will mother and child have found each other.

The house is well-kept. There’s the sound of someone bustling about in the kitchen. Anahit is happy with her life. She is energetic and full of life – she handles a lot, including all her affairs at home, work and volunteering. She can’t afford to get tired – there’s no time for it. She has to get her sons to school, then to speaking lessons, aircraft modeling, drama classes… She wants to give her children all she can and even more to make up for what they didn’t get before.

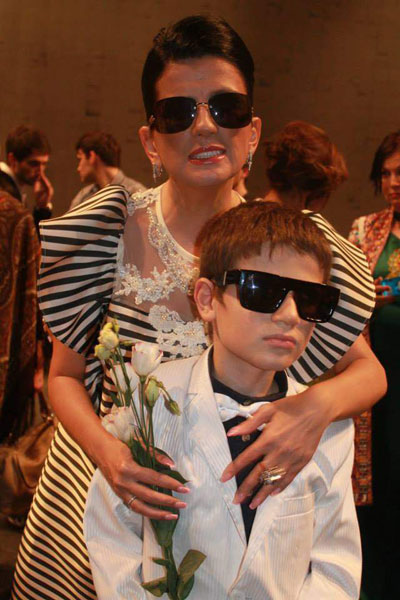

On the piano are photographs in beautiful frames – the pride of their mother. The eldest son, Hovhannes, is depicted after having sung a duet with a well-known singer. “At an international competition of blind singers with more than 400 contestants, he was chosen by Diana Gurtskaya to sing in ‘He’s my star, my joy’,” says his mother.

In another corner of the room is her younger son, Husik, sitting in a rocking chair. He doesn’t like being the younger one in the home, but he immediately says:

“This isn’t my chair, they gave it to my older brother Hovhannes.”

Anahit’s husband, Grigor Hovhannesyan, is a priest. Together they raised a daughter who has already married and left their home. The couple always helped those that were in need when they could. Together with the youth wing of the Surp Sargis [Saint Sargis] church of Argavand village, Father Grigor and his wife Anahit visited the Mari Izmirlyan orphanage every Sunday. It’s already been some time since they’ve organized summer activities at the seaside for children.

Five years ago Anahit decided for the first time to take blind and wheel-chair bound children on vacation. The responsibility was enormous, but there was a solution: Anahit found a volunteer for every child. After the camp, she understood that a love had awoken in her – not an abstract one, but a concrete one.

On her birthday which followed soon after the experience, her husband asked her what she would like.

“I don’t know why I felt it in this moment, but I knew I needed Hovhannes. I said that I would like Hovhannes to be there. It was already late, practically night-time. It wouldn’t work to bring the child here then, but I think that day was decisive – I understood that in the world there is someone very important to me, someone that wasn’t by my side.”

The couple started to gather the documents needed for the adoption. The process was long and difficult and went on for more than a year. She says that those who want to adopt a child must know that it is difficult and requires patience. But it is nothing in comparison to the happiness that it brings to the home.

Five years ago, Grigor and Anahit became the first family in Armenia to adopt a child with a disability. The parents looked after the health of Hovhannes. The boy’s medical documents said that the likelihood of his sight recovering was equal to zero, but Grigor insisted that additional tests be conducted. His heart told him that the boy would see again. The new test results showed that the optic nerves of one of Hovhannes’ eyes was working and needed an operation. Hovhannes received his first operation in Israel and then another in Canada, and they need another six years before the results will be conclusive.

“Many ask: ‘How can you wait all this time?’ I tell them that if there is even the slightest possibility that my son will be able to see, or at least differentiate between light and dark, we are ready to wait and do all we can,” says his mother.

The school bus brings Hovhannes home at 4 o’clock sharp, and his mother rushes to meet him.

“Where’s my son? What, have you forgotten my treasure behind?!” she jokes with the driver while she opens the door. Her son doesn’t hurry. This is a traditional game he has with his mother. In a few seconds he stands and goes forward: “There’s my treasure! And here I was, all afraid,” she says.

This well-behaved and brought-up boy has learned to read and write at just ten years old. He has very little free time: after school he has speaking lessons, then theatre, and at home his tutor waits for him. His parents are trying to make up for what he missed out on earlier.

“It was the happiest day of my life when Hovhannes was able to read a word without trouble. By depriving children in orphanages of a quality education, they are condemning them to being beggars and thieves. They are taking away the possibility of living with dignity,” says his mother.

It would seem that no one at home remembers that Hovhannes cannot see. He takes off his shoes by himself, puts on his slippers and home-clothes and goes to wash his hands. His mother turns on the light in the bathroom. Hovhannes says that he wants to become the mayor of the city, but he is worried that he won’t be able to continue with singing if he becomes the mayor. His mother is sure that he’ll be able to.

What will these children be capable of?

According to data from the UN Children’s Fund, every fourth inhabitant of an Armenian orphanage with a disability never leave the grounds of the orphanage except to visit a doctor.

They remain practically entirely outside the education system. Only 5% of them go to regular schools, 23% go to special schools and 72% don’t go to schools at all.

Boys with disabilities that live in orphanages are more likely to have no friends (19%) than girls are (12%).

Save one more: Husik

“Husik ended up in our family a year after Hovhannes did, and that was much in part thanks to Hovhannes. Once he simply asked why the family shouldn’t adopt one more child. I think that Hovhannes had the desire for a long time to save just one more, to bring them home into the family and give them a dignified life. Husik was not against the idea of joining our family,” says Anahit, looking at her fidgety son who, out of his mother’s sight, tries on his brother’s coat which he’ll be receiving next year.

Husik was friends with Hovhannes in the orphanage. He was his eyes, and Hovhannes his legs.

“I want to be a vet, but I won’t stop playing the dhol and kemenche [Armenian instruments],” Husik says.

After an operation three years ago, he was able to walk more confidently. He jumps from his spot, runs to his room and brings back a small plane made from an empty cigarette box. He made it at his first lesson of airplane modeling – it even flies.

Anahit believes that children must be involved in engaging activities – idleness is the mother of all vices.

Husik was in the fourth grade when he ended up in Grigor and Anahit’s family. He wasn’t able to read at first, but within three months he picked up the entire curriculum for the four years he had missed.

“When I understood that the child couldn’t read, I went to the school to lodge a complaint. In Hovhannes’ case I sort of understood the situation. It’s hard to teach braille. But Husik only had a problem with his legs – he has a highly intelligent mind,” says Anahit.

Husik receives all the privileges of being the youngest in the family. His mother says that he is naughty but that he has a heart of gold.

They decide to take a family photo by the new rocking-chair. Hovhannes tries to get up on the ‘throne’. He still hasn’t had the opportunity to study the chair carefully. Husik warns us: “You don’t need to help him. He can do everything by himself.” And in fact, he can.

They never talk about what they don’t have in this family. And what they do have is so appreciated that they don’t even dream of having more.

The best mother

A few days after the birth of her son, Anna understood that she couldn’t live far away from him:

“It will probably seem strange, but this overwhelming hatred didn’t break me, it made me stronger. I wanted to prove to everybody that both me and my child can live happily, and that our lives would never be dependent upon the attitudes of others towards us. We are one another’s friends, and for that we are only stronger,” says Anna.

It was only two weeks after giving birth that she took her son in her hands, and she has never let him go. Anna believes that her son will never judge her for those lost two weeks. Children forgive easily. It was hard for her to forgive herself, however, but this has already worked out for her. In this new life with her son, there is no room for worrying about past mistakes.