A view from Baku – three scenarios of how things may unfold in Karabakh

The second Karabakh war which came to an end on November 10 lasted 44 days, claiming more than 5,000 lives in total on both sides, with the number of casualties likely to increase as time goes on and more data is announced.

Azerbaijani journalist and political observer Shahin Rzayev offers three possible scenarios for the development of events in Karabakh below.

What happened

“Victory was stolen from us!” a relative told me when she heard about the trilateral armistice agreement on November 10.

Indeed, the Azerbaijani army was just a stone’s throw from the capture of Khankendi, the center of Nagorno-Karabakh, a former autonomous region within Soviet Azerbaijan, around which one of the bloodiest wars of the late 20th century erupted in the early 1990s, and now again in November.

But on the night of November 9-10, the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia, with the mediation of the President of Russia, signed a document that stopped the war and outlined the general outlines of a future peaceful settlement.

This document was met with hostility both in Azerbaijan and especially in Armenia.

- Op-ed: What’s next in Armenia – loss of sovereignty or global integration?

- The road to Nakhichevan: is Armenia surrendering its territories to Azerbaijan or emerging from blockade?

In Azerbaijan they demanded a war “to a victorious end”, in Armenia the authorities were accused of “betrayal”.

Only one month has passed since the first-ever “online peace agreement”. Time, of course, is not enough, but nevertheless, the first conclusions can be drawn.

The primary euphoria of the majority in Azerbaijan began to gradually subside. Of course, the suffering and resentment that lasted for about 30 years will not go away immediately.

Now we all need to gather our strength about us and together overcome the hatred and gloating. I understand my Armenian colleagues, I was just as angry and annoyed with the malicious remarks in 1994, although the Internet wasn’t so pervasive then.

Why now

The first thing that comes to mind is a rather controversial saying: “Better late than never.”

Foreigners sometimes ask: “Is it true that Azerbaijan started military operations”?

I don’t know exactly who fired first on September 27. But there have been a great many such shots since 1994, and never such consequences.

Undoubtedly, Azerbaijan has been preparing for this military operation for a long time. It has consistently increased its military budget, bought the newest military equipment, and carried out active diplomatic work.

And to be honest, it had every right to do so. Azerbaijan also acted on its territory in accordance with the resolutions of the UN Security Council.

The timing was also wise. The new authorities of Armenia had tired out their closest ally (patron) – Russia.

Before the start of the second war, heavy ‘artillery preparation’ towards Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan began in the Russian pro-government media (Russia Today).

He was accused of almost all sins, and the worst of all: ‘of coming to power by cooperating with the Soros Foundation.’

In addition, the first euphoria from the Velvet Revolution of 2018 passed in Armenia, and the people had begun to expect concrete results from the new government – but instead received weekly demagoguery on Facebook.

The rating of Pashinyan and his My Step faction had begun to fall.

At the same time, presidential elections were being held in the United States, and Trump had no time for the Caucasus. Europe is mired in coronavirus. Only France adopted non-binding resolutions, but no one really heard them.

Everything was most likely agreed upon with Russia and Turkey in advance.

Could war have been avoided?

War for territories at the beginning of the 21st century, even at the end of the 20th, seems like an anachronism.

In theory, of course, a new war could have been avoided. And the most reasonable way to this was proposed by the first President of Armenia Levon Ter-Petrosyan in the fall of 1997:

“The denial of compromise and maximalism are the shortest path to the aggravation of the situation in Armenia and the complete collapse of Karabakh. It’s not about returning Karabakh or not. The point is to keep Karabakh Armenian: for three thousand years it was inhabited by Armenians and should be inhabited by Armenians for another three thousand years.

The path I have taken will provide this perspective. Armenia and Karabakh are now stronger than ever, but without a settlement in a year or two they will become incomparably weaker. What we reject today, in the future we will have to pay for – as has happened many times in our history.”

Armenia could have abandoned its maximum demands, liberated the occupied areas around the former Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan and negotiated a status that would ensure equal rights for both the Armenian majority and the Azerbaijani minority in the region.

But Ter-Petrosyan was overthrown, the new authorities of Armenia decided to drag out the negotiations indefinitely. As they say in the East, ‘either the khan or the donkey will die’ (one is bound to disappear first).

And Nikol Pashinyan’s “seven conditions” put an end to the negotiation process.

As for Azerbaijan, all it ‘had’ to do was give up Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, and preferably two more regions – Kalbajar and Lachin – ‘as a bonus’. And maybe Nakhichevan too.

What’s next?

Further, Karabakh will face three development scenarios: secession, conservation or integration.

Or in simpler terms: separation, freezing or consolidation.

Let’s consider all the pros and cons for the Azerbaijani side.

Secession

The territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, more precisely, that part of which is now under the protection of the Russian peacekeepers, would be transferred to the control of Armenia.

Of course, not free of charge, but in exchange for a comparable territory, for example, a strip along the Armenian-Iranian border for the land connection of the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic with the rest of Azerbaijan.

This plan is not new, it was discussed during negotiations in 2001 in Key West, USA.

The advantages are obvious:

A part of the body has been cut off which caused so much trouble and is guaranteed to continue to deliver discomfort.

One can calmly, without looking back at the front line, engage in the restoration and development of the rest of Karabakh, including lower Karabakh (Aghdam, Fizuli, etc.).

The corridor to Nakhichevan passes under the sovereignty of Azerbaijan, and does not remain under the control of the peacekeepers, as provided in the text of the November 10 agreement.

There is one minus, but it negates all the pluses:

Why did the soldiers and officers die, since the territory would have to be given up anyway?

Conservation

The condition of ‘no peace, no war’ state is extended indefinitely, now with the participation of Russian peacekeepers.

If we call everything by its proper name, it means that Azerbaijan and Russia have divided Karabakh between themselves.

To me personally, this option seems worse than the previous one – at least there is clarity there.

All the same, in the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh, for example, in Khojali, the Azerbaijani settlers will not be able to return in this situation. What then does it matter who is the boss there – Armenians or Russians.

And history proves that the Russians, having entered some territory, almost never leave it.

This option, as a constant pressure on both Armenia and Azerbaijan, in my opinion, should not suit either side. Nevertheless, it is still the most probable.

Integration

Gradually, the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh is united with the rest of the territory of Azerbaijan, with which it is closely connected geographically.

But integration doesn’t have to mean assimilation. For full-fledged and painless integration, a special status is required for the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh. A status under which all political and human rights of both the Armenian majority and the Azerbaijani minority will be guaranteed.

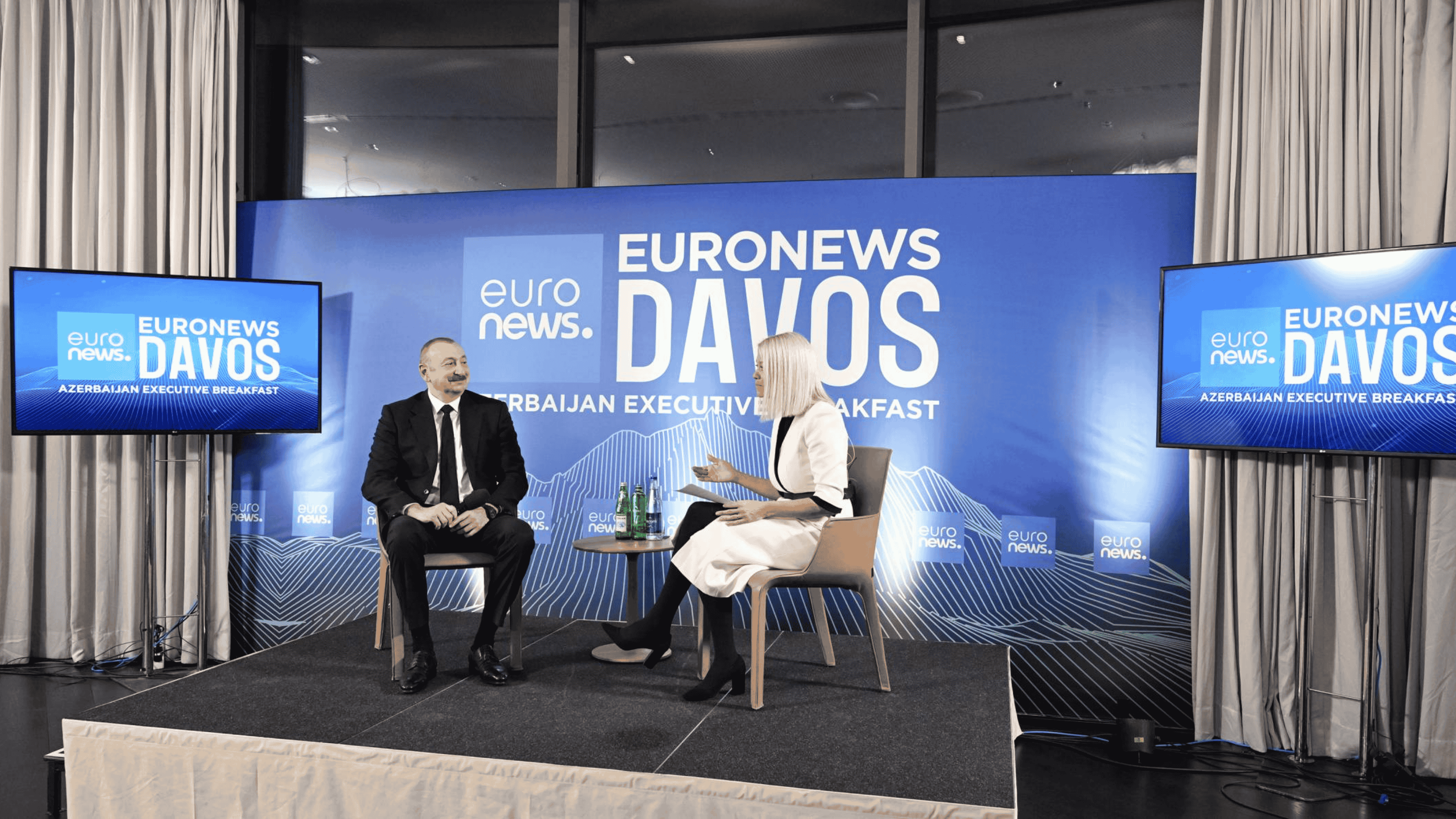

Today, President Ilham Aliyev says that there can be no question of any special status (unfortunately, he says this in more terse terms).

But an interesting detail, he added last time: “As long as I am the president.”

And he is still president until 2025. In the same year, the five-year mandate of the Russian peacekeepers expires.

It seems that 2025 will be a new milestone in the history of the Karabakh conflict.