What does war see in the mirror?

Karabakh conflict in cinema and literature

Across the world, war has always inspired a separate genre of popular culture, of pictures, films and books. Twenty years since Azerbaijanis and Armenians ended up on different sides of a front line, how is the Karabakh conflict reflected in this mirror?

Feature films

There’s no shortage of films about Karabakh. Since the start of the problem tens of feature films have been made. Among them are pictures that have been praised nationally and internationally, as well as others that were panned by critics. The most recent have, as a rule, been accused being clumsily made and jingoistic, made “without heart or proper thought”.

One film that was made with enough heart and thought, is Faryad (The Scream) by Jeyhun Mirzoev, made in 1993 when the war was in full swing. The film is very emotional, and, as its creators stress, is based on the real stories of refugees from Karabakh, a number of whom even took part in filming.

Faryad is also in some way a sequel to the famous 1958 Azeri film Ogai Ana (The Step Mother). The film’s main character, a boy called Ismail, grows up to go fight in Karabakh and ends up getting taken hostage. Most of the film is not taken up by battle scenes, but rather the interaction of Ismail (played by the director himself) with those holding him hostage.

Alongside the outright cruelty of some of the Armenian characters, the makers of Faryad also show others who sympathise with the prisoner and don’t harbour any hate towards him or Azerbaijanis in general. There’s a doctor, originally from Baku, who, upon seeing the injured Ismail, whispers to him that he himself is against the war. The niece of the main villain pities Ismail and hates the uncle who makes him suffer.

But what is considered to be the very best piece of cinema on the subject is not any full-length film, but the short film All for the Best by Vagif Mustafayev (1997). This 35-minute tragicomedy is very distinct from any other film made in Azerbaijan about the Karabakh conflict, although it is not about the actual war as much as about people’s reactions to it away from the frontline.

A coffin containing the body of an Armenian solider accidentally finds its way to Baku, and nobody seems to know what to do with it. So they drag it across town, trying to get someone to take it, all the while speaking in Russian (in deference to the deceased). All of this plays to the sound of a happy children’s song about chickens. Ultimately, it is decided to give the body back to the Armenians in exchange for “one of our own”.

You understand that the main character of the film is death, but in such farcical surroundings, death also seems unreal, and it seems that the war itself is unrealistic, a farce that could not and cannot be serious. Or at least it shouldn’t be.

All for the Best won a prize at a festival in Oberhausen, but it’s probably better represented by the positive – and even enthusiastic – reviews from audiences in Armenia.

In the 2000s Elkhan Jafarov made three films about Karabakh, more than any other director:

- The short film Karabakh is Azerbaijan (2009) – a type of requiem for an Azerbaijani hero, taken hostage and tortured to death.

- The feature-length film Grad (2012) based on the novel of the same name by Agil Abbas, tells the story of the misadventures of a small band of Azeri volunteers.

- The feature length film Interrupted Memories (2015) – the main character is a WW2 veteran who took part in the defence of the Brest fortress with Armenians and other Soviet nationalities and suffers from the fact that his old friends and comrades have now become enemies.

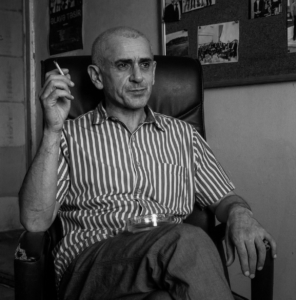

“All these films (especially the second and third) I made with one overarching aim – to explain Karabakh to the youngest generation.

After all, people born in the 80s and 90s really don’t understand what’s going on. They don’t know how Armenians and Azeris used to live side by side nor how hard it was for them to then shoot at each other.

So I wanted young people to feel and understand at least a little, and not grow up in an atmosphere of blind hatred. But now I think I’ve said everything I can about Karabakh.

It’s unlikely I’ll come back to the subject in the future. It’s time for other films now”.

Cinemas only rarely show these kind of films except for during festivals. So the director and and his colleagues have higher hopes for TV and the Internet, and in that way be able to penetrate potential younger audiences.

Elkhan Jafarov about the Karabakh conflict

Literature

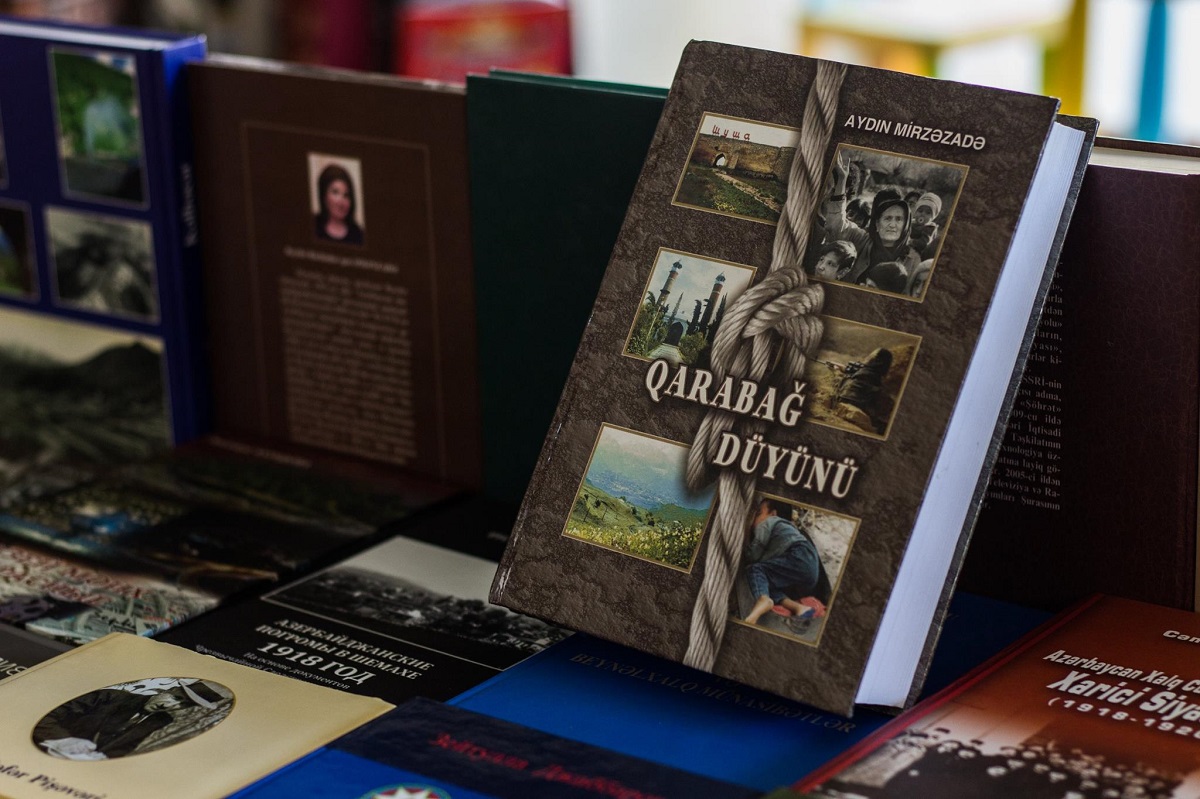

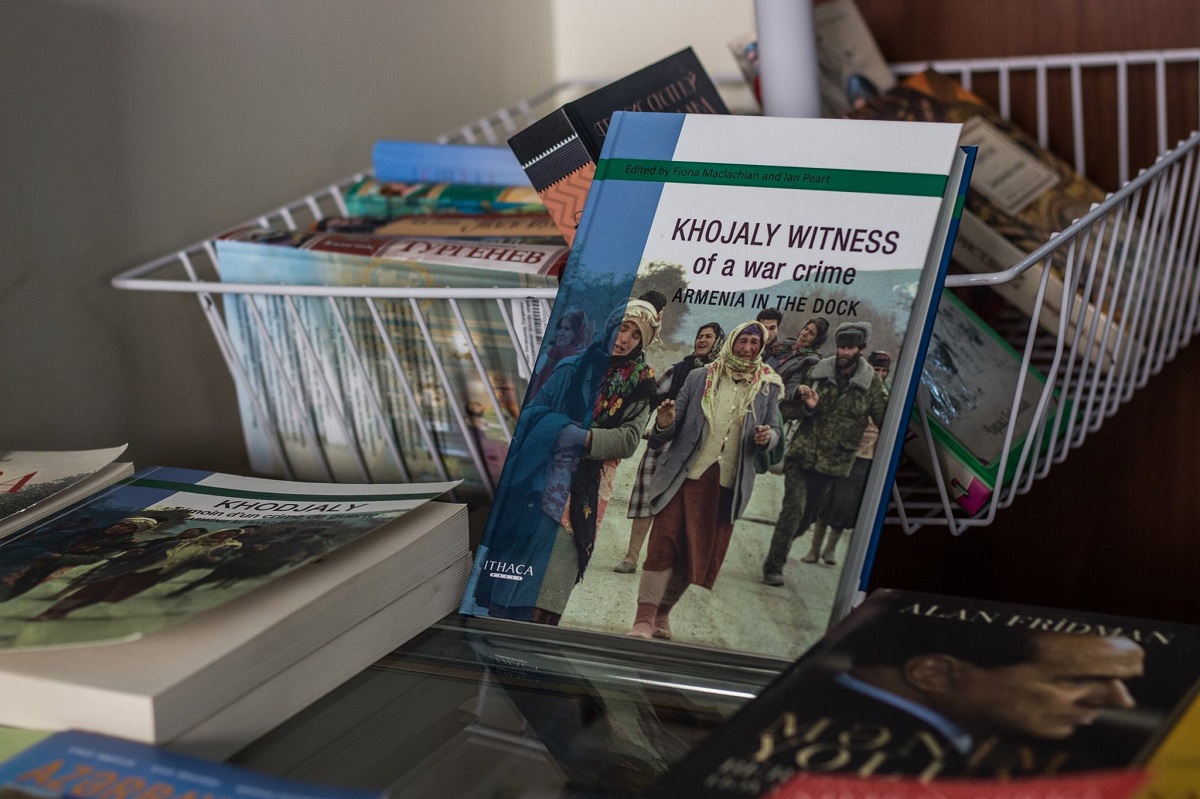

The situation with literature is paradoxical. On the one hand, you can find a great many books about the Karabakh conflict if that’s your goal. But a lot of those are actually self-published and so aren’t well-known, even by experts on the issue.

A number of poems on the subject were put into school textbooks, with the aim of nurturing a sense of patriotism in children. There is a mountain of journalism on the conflict, but the most well-known book on the subject (at least by a journalist) is Black Garden by Thomas de Waal, who isn’t a local author.

Apart from these, there is the novel Artush and Zaur, which is funny and sad at the same time. It caused quite a stir eight years ago yet today it is almost forgotten.

The book served the public a double provocation: the main characters were a gay Armenian-Azerbaijani couple. In the words of the author himself, he tried to attack stereotypes, specifically the habit of Azerbaijanis to stigmatise anyone they didn’t like as gay or Armenian.

The novel was published in 2009 and bookshops said copies were bought like they were condoms, coyly hidden between books by Nietzsche and Stephen King. Moreover, what interested people most was who took on which role in the couple.

Admittedly, today few people remember Artur and Zaur in the context of the Karabakh conflict.

There is only one novel about Armenian-Azeri relations, that caused such a stir that people still know it today, even if they don’t read many books at all. Akram Aylisli, the author of Stone Dreams, has been condemned in his homeland while abroad he’s seen as worthy of being a nominee for a Nobel prize. This is because “dreams”, according to many Azeri readers, appears to be a repentance for the Armenian people. The events of this novel-requiem (as Aylisi himself called it) takes place in two different time periods:

- At the beginning of the 20th century in the Azerbaijani village of Aylis, where many Armenians lived;

- And in Baku in 1989 at the start of the conflict between the Armenians and Azeris.

Through the words of his main character, the author mourns the Armenians who once lived in Aylis, for which some critics have compared him to Orhan Pamuk.

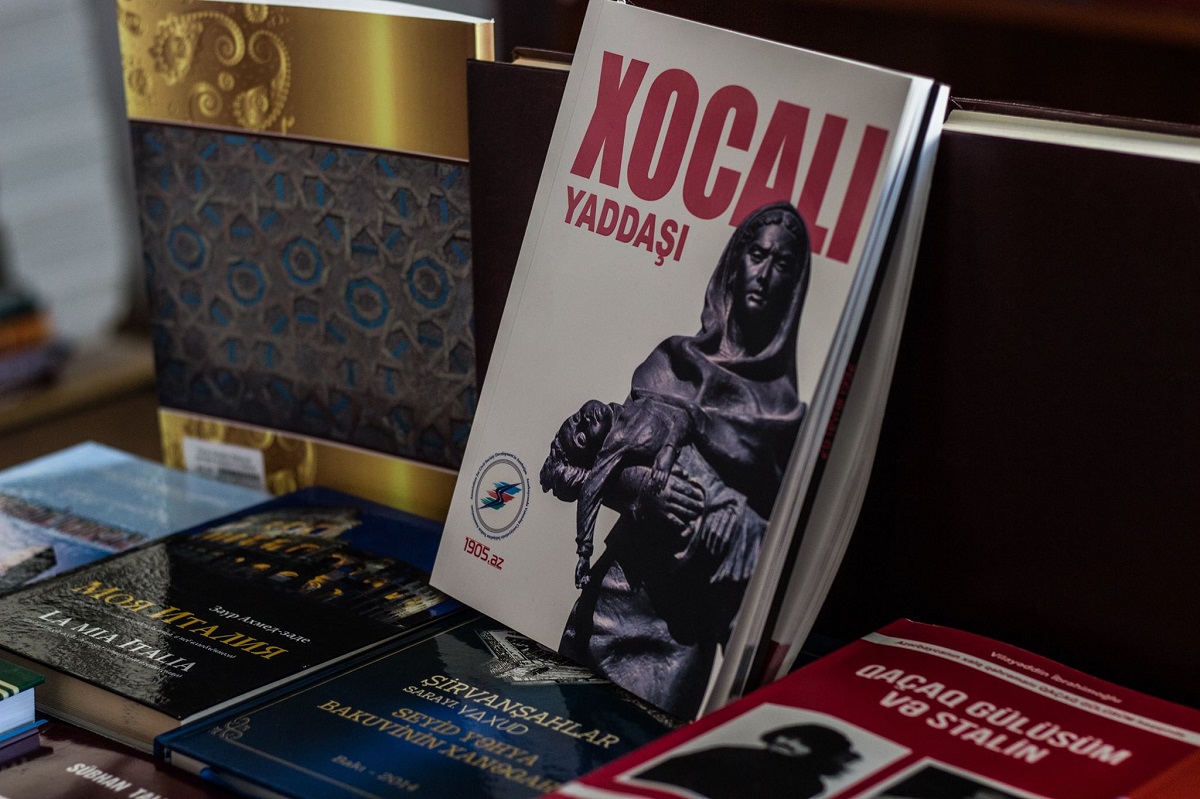

Novice writer Agil Hajiyev dreams of the day his work becomes known worldwide. As it stands he has so far only been able to publish in Baku – in January this year his first novel, He was from Khodjaly, went to print.

The novel was 10 years in the making. It was written after Hajiyev, who had served on the front line, listened to stories about the war and met with refugees living in an old train car.

What made a particular impression on him was meeting a teenage boy, whose family had been killed in Khojaly, but who had managed to survive. He became the main character of the novel.

Ultimately it ended up being a story of thoughtless and ruthless revenge that affects everyone around him, including himself.

“From the beginning, I wrote this book for an international audience.

I understood that those readers don’t need to be told a bloody horror story about how good Azerbaijanis are and how bad Armenians are. Especially since that’s just not true.

Both nations have good and bad people. So in my novel I tried to show both types of people on both sides.

The Karabakh conflict gave birth to a lot of journalism of very different quality and poems that have gone into school textbooks, but there is no work of fiction, which has seen widespread interest, even inside the country.