Ali and Nino, or whatever is left of them

How I was starring in this film

A tight corset prevented me from drawing a breath, making it obvious why the ladies fainted so often in olden times. It was February and it was rather cold in a thin evening gown. In addition, half a hundred of hairpins caused an unbearable headache in the evening. But, on the other hand, a real beautiful costume movie was being filmed. There was an incredibly delicious creative atmosphere, and the friends were jealous that you could see real Maria Valverde wearing uggs.

I got engaged in the process of shooting ‘Ali and Nino’ movie by chance, in the modest capacity of a background actor. Frankly speaking, I was surprised at seeing the scope of what was going on there. A scene of the ball at millionaire Zeynalabdin Tagiyev’s place was filmed for three days, days, from sunup to sunset. Husky director assistants rearranged the crowd, whereas Ali and Nino came out to perform an oriental dance time after time. Indeed, it was so cool that at some point I nearly agreed with Vladimir Ilyich Lenin that cinema is the most important art for us.

And, naturally, ‘after what had happened between us, I simply had no moral right not to see this movie. You know, Vladimir Ilyich…let me tell you that you were wrong.

The Caucasian Romeo and Juliet

The film is based on an eponymous novel by Kurban Said, the Azerbaijani immigrant writer. Having been written in German language in 1937, it managed to cause great stir and, according to the articles and book description, the western public found it quite appealing. Actually, why not? There is an exotic Eastern country, a forbidden passion and the grand historical events.

A romance between young Khan, Ali Shirvanshir, and Georgian duchess, Nino Kipiani, is at the heart of the novel. He is a Muslim of higher principles, whereas she is a freedom-loving and Europeanized Christian. The developments took place in Baku, in early 20th century. There was an oil boom, the war, the revolution, Azerbaijan’s struggle for independence and the debates on whether it should be an Asian country or it should ‘move to Europe.’ On the side note, we’ve been discussing it for hundred years already and this issue still remains open. ‘Ali and Nino’ is essentially a novel about confrontation between Muslim and Christian, European and Asian cultures, illustrated by the case of a separately taken couple. And it’s also about love that is stronger than all those controversies.

It could be even said that ‘Ali and Nino’ is, in its own way, a symbolic work for the entire South Caucasus. At least that’s how Tamara Kvesitadze, a Georgian sculptor, regarded it. She is an author of ‘Ali and Nino’ mobile sculpture, installed on Batumi boulevard.

So, in light of the aforesaid, it’s quite obvious that when it was decided to produce a screen version of the novel, everyone in Azerbaijan wondered, how it would play out.

The People’s Voice

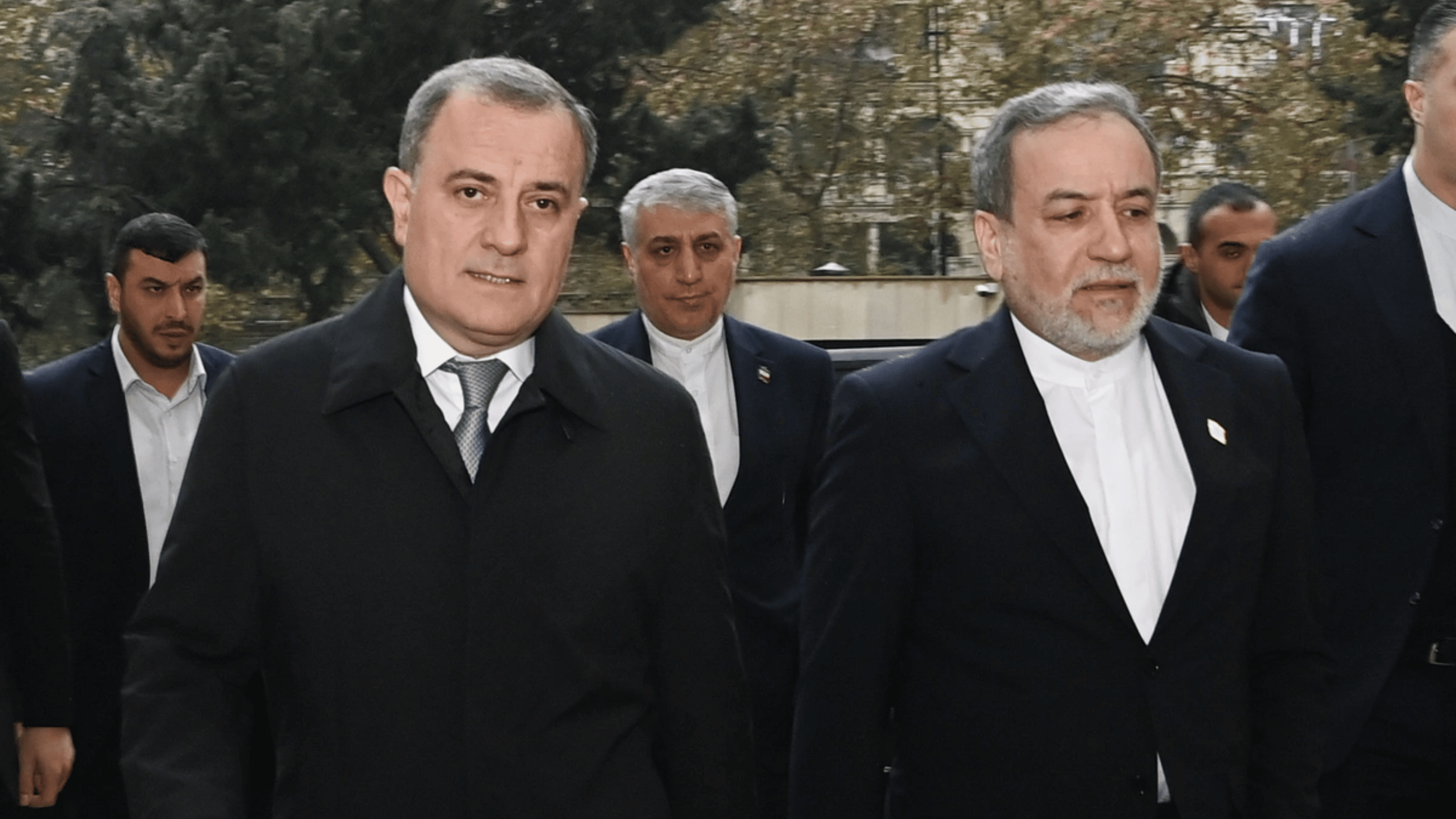

The film was produced by the British PeaPie Film company in 2015. Asif Kapadia was the film director, whereas the script was written by Christopher Hampton (to whom Kurban Said is now supposed to come in dreams and give a look of reproof till the end of his life).

The film’s executive producer was Leyla Aliyeva, Vice-President of the Heydar Aliyev Foundation. As for the lead actors, Maria Valverde, the Spanish actress, and Adam Bakri, the British of Arab origin, were selected to perform the main characters.

The film was premiered at the U.S. Sundance film festival, last winter. It didn’t leave the critics and journalists speechless from admiration.

Here’s what the Little White Lies film portal wrote about it: “Taking its cue from sweeping historical epics like The English Patient and Doctor Zhivago, Ali and Nino centers on a romance in the midst of a continent-defining war. The major difference is that Kapadia’s film is closer in relation to a tea-time TV drama than to those Oscar winners. In addition, the filmmaker is reproached for making some scenes look like ‘a pure slapstick’.

The Hollywood Reporter website, in turn, believes, the film has had pretty good chances to become a great historical melodrama if the actors would have played love in a more plausible manner.

At the same time, both resource (actually, like many others) share the opinion that landscapes are the best thing in the movie. The Hollywood Reporter has even found similarities between Baku surrounding areas and Texas in oil boom times. It seems, it was a compliment.

The film has been screened in Azerbaijan since October 6, and, quite naturally, has been actively discussed on social media. And while part of the audience squeamishly turn their noses up, another part couldn’t hide its exaltation.

For example, one of the Facebook users has drawn parallels with another well-known screen version: “I don’t care about the Civil War in America, in principle. However, thank to the ‘Gone with the Wind’, I’m still interested in this theme. So, will this film kindle the interest of millions of foreign viewers in the history of our Republic? I’m not sure about it.

Khadija Ismayilova, a prominent journalist, has absolutely different opinion. In her words, the film’s key message is quite clear to the Western world and will produce the effect desired by Azerbaijan.

“I’m very glad that the final version of the script doesn’t intrench upon the truth and truthfully portrays the bloody developments of that time and our struggle for freedom, Khadija wrote on her page – “Of course, the film isn’t ideal in terms of reliability of historical facts, but nevertheless, it can tell the world what we want.

“In my opinion, this film is a rough work, says another user. “The main things it lacks are feelings and emotions. Even the scene, when one of Ali’s friends is killed, doesn’t cause any sympathy in the audience.

Whereas some people found there were more than enough emotions in the film: “I really enjoyed it very much. I even cried at the end. I don’t know, maybe it’s all about my sentimentality. And also, I was really hooked by old Baku scenery.

Right off the bat

In fact, it’s hard to call the film ‘Ali and Nino’ an adaptation. The scriptwriter treated the original in a rather bold manner. And it seems that many of the scenes were ‘killed’ right at the editor’s table, as it usually happens. After all those manipulations there wasn’t much of Kurban Said’s work left.

But let’s discuss first things first.

If you read the book, in the beginning of the film you can’t get rid of the feeling that you’ve missed that very beginning. That is, the film ‘starts’ approximately from Chapter 12 of the novel. Unlike the novel, in which Kurban Said provides the detailed descriprion of his characters’ first meeting and further development of their relations, in the film all the aforesaid is left behind the scenes. What actually gets in shot is a kaleidoscope of some brief scenes with confessions, kisses and exchange of glances. By the way, that very ball scene is show in the film in fragments, and what is more, against the background of the closing credits.

Perhaps it’s ‘right off the bat’-style beginning that makes Ali and Nino’s cinematic love less plausible. Maybe the western critics are right, when they unanimously claim that there is a ‘lack of chemistry’ between Bakri and Valverde.

The film’s dynamics is what surely can’t be denied. The developments are unfolding so quickly that it’s hard to keep track of them, even if you know the chronology of the events. The World War I breaks out before the young Khan could get his father’s blessing to the marriage. And then 4 friends are shown arguing about whether the Muslims should to go to the front or the ‘war of the unfaithful’ isn’t their concern.

By the way, as far as the friends are concerned, Ali has 3 friends and, based on the novel, each of them has his own character, advantages, disadvantages, etc. Whereas in the film, these characters (actually as the majority of other characters) are practically deprived of any individuality. A fanatic Mullah, a selfless young officer, an old conservative – all of them aren’t the human beings, but rather the stickers with inscriptions, stuck to the actors’ foreheads, like in the ‘Guess Who?’ game.

The film authors also pretty much ‘adjusted’ the image of Malik Nahararyan, an Armenian aristocrat and, at the same time, Nino’s abductor. Firstly, the role of pudgy and unappealing Nahararyan was offered to a green-eyed handsome Italian actor, Riccardo Scamarcio. Secondly, for some unknown reasons he was turned from Ali’s close friend into a ‘second cousin twice removed’, a partner of Nino’s father. This substitution considerably reduced the dramatics.

The ‘fate’ had no mercy to the main character, Ali Shirvanshir, either. In the novel, he commands respect mostly due to his internal struggles and the attempts to find a balance between his love to the European woman and his commitment to the Asian foundations, between his understanding of morality and the demand of the times. However, this inner struggle hasn’t been reflected in the film. Not a single drop of psychologism has befallen Ali – just gun-firing and high-flown phrases ‘I love my homeland!”

… Meanwhile, the film session continues and while you are thinking about the young Khan’s image, the shots keep flickering on the screen, overrunning each other. By the way, those are beautiful shots. Very beautiful indeed. And here’s the scene where Ali has already killed his opponent, who was trying to abduct Nino, and has fled to Dagestan so as not to become a victim of vendetta. And now, Nino travels there, to his place, like a Decembrist’s wife (Decembrist – a participant in December uprising in Imperial Russia). Here they hastily get married and settle down in full harmony. But then the revolution breaks out, turning everything upside down in Azerbaijan. Ali’s enemies disappear in an unknown direction, and he can get home. Moreover, Ali’s father, who comes to visit the newlyweds in their village, somewhat casually informs them about this fateful event some three hours after his arrival.

An alternative story

From this moment on, in order to understand what is going on on the screen, you need to be an expert in history. Otherwise, it’s absolutely unclear, who’s fighting who and why. Though, if you are well-aware of what happened in Azerbaijan in the period from 1917 till 1920, there is another ‘reef’ waiting for you. Or, to be more precisely, the stones – numerous historical bloopers.

That’s exactly what caused indignation in the most educated part of the audience. Suffice to mention the most striking blooper – Azerbaijani tricolor flag, waving proudly at the moment of proclamation of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic. As a matter of fact, this flag didn’t exist at that time (May 26, 1918). It first appeared just 6 months later. In addition, the very ‘ceremony’ of proclamation of the ADR in the military camp, somewhere in the steppe, leaves a rather strange impression.

The history of ADR, as well as other events in the Caucasus in that period, in general, are really very interesting and important. And they should have been properly shown. But it didn’t work out.

And if this film is viewed as a historical movie, designed to tell the world about the formation and collapse of the first democratic republic in the East, this mission could be regarded as completely failed. An average western viewer, who isn’t burdened much by special knowledge, will hardly understand anything. Because, judging by the film, ADR is some weird republic in the Caucasus, which appeared literally overnight, from thin air, through the efforts of a mustachioed man named Khoyski. And it turns out that it was ruled single-handedly by him and a couple of young guys. The most inquisitive viewers will probably go to Wikipedia after the film session. Others will just pull the plug.

Too ‘tolerant’ movie

The artistic value of ‘Ali and Nino’ novel is rather debatable, but it at least contains two necessary components – a logic and a conflict. Meanwhile, the film practically doesn’t have either of those. The logic in the characters’ actions is very doubtful, whereas the conflict is represented maybe by a confusing confrontation between Azerbaijan and Russia, and also by a lethargic grumbling of Nino’s parents, addressed to her beloved one. However, the young people’s main stumbling stone – their religious and cultural difference, is omitted. And that deprives the entire story of the bulk of sense.

Islam is obvious, so to say, ‘out of fashion’ nowadays. The filmmakers probably didn’t want to once again focus on the strict Islamic canons and this theme, in general. Sorry to say, but a word dropped from a song makes it all wrong.

Epilogue

After the film you’ll have an impression that you have watched a 90-minute trailer for some series. Or that your friend tried to hastily tell you his life story and got confused himself.

There is no sense watching the movie until you read the novel. You simply won’t understand what’s what and who all those people are.

But, on the other hand, if you haven’t read the book yet, it’s a great occasion. Don’t worry, you can wade it through within a day. I’ve tried it myself.

Published 20.10.2016