"Armenia and Azerbaijan join US AI projects as Georgia falls behind" — opinion

AI in Armenia Azerbaijan and Georgia

By ratifying the peace agreement in Washington on 8 August, Armenia and Azerbaijan also joined US initiatives in artificial intelligence (AI). For Georgia, such strategic opportunities remain out of reach, writes Georgian journalist Gvantsa Kvinikadze.

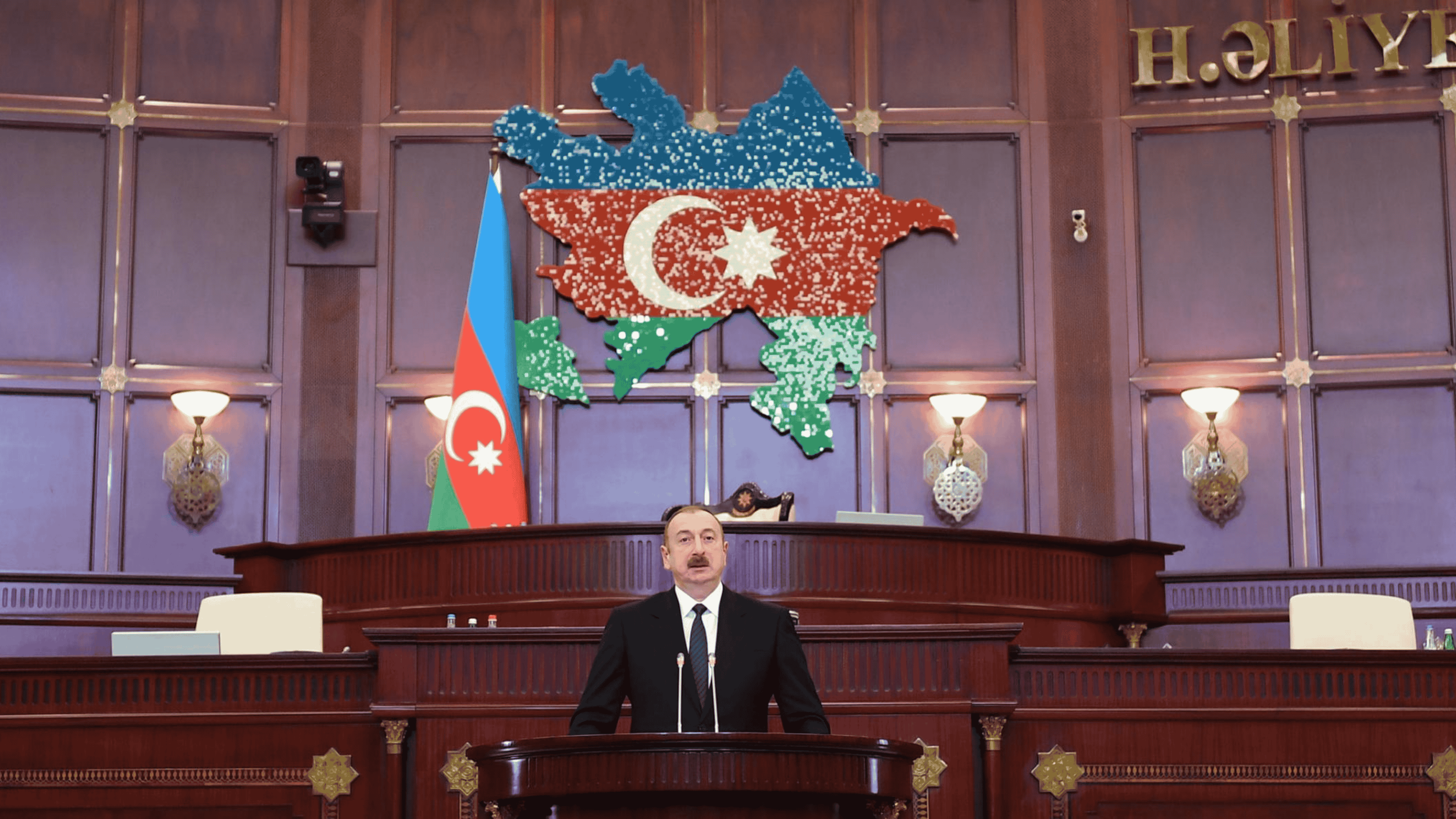

Many in Georgia believe that the Washington peace deal, mediated by president Donald Trump between Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders,

effectively left Georgia on the sidelines of major regional developments.

Reconciliation was not the only achievement of Ilham Aliyev and Nikol Pashinyan in Washington. Other documents were signed to help Georgia’s immediate neighbours advance in a very different, but no less important, field.

These were memoranda of understanding between the US and Azerbaijan, and the US and Armenia, on developing bilateral cooperation in artificial intelligence.

AI as a new geopolitical dividing line

During and after the historic Washington meeting, debates in Georgia focused heavily on the peace deal, its impact on regional security, and the prospects of a new reality through reopened transport links and trade.

By contrast, the AI memoranda went almost unnoticed. Yet it is AI that is already reshaping the global geopolitical order, driving trade and tariff policies in major states and becoming a central theme in national security.

The war in Ukraine is the clearest example: even the use of drones there has shown the transformative power of AI.

Many in Georgia still treat this as a minor issue, while Armenia and Azerbaijan are taking a strategically wise step: by working with the US on AI, they are becoming part of regional processes in innovation and security.

Our neighbours clearly understand that artificial intelligence offers huge opportunities in attracting investment, creating new jobs, introducing cutting-edge technologies and building expertise.

But it is not only about the economy.

In recent years, the rapid development of AI has sharply intensified competition between the US and China. This “hidden race” has taken on a distinctly geopolitical character, drawing new dividing lines in the world.

As during the Cold War, the world has split into two camps. On one side are the democratic and wealthy countries aligned with the US — the European Union, the UK, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia and others. On the other are the BRICS states and developing nations clustered around China.

This division is not just ideological. It is based on technical standards, state regulation, infrastructure and different philosophical models. Technology exchange and transfer require trust and security, which means the dividing lines will only become sharper in future.

Why it matters

Given the nature of the sector — requiring huge investment, highly qualified specialists and advanced technical resources — these agreements primarily benefit US tech giants.

Azerbaijan, Armenia and, if the chance arises, Georgia are likely to contribute mainly territory, infrastructure and, to some extent, skilled staff for building data centres.

And this is not as unappealing as it may sound. It is fundamentally different from the late-20th-century practice of Western companies opening factories in developing countries.

Today, major firms such as Amazon, Meta, OpenAI, Google and Anthropic build most data centres in the US (51% of global AI centres are in the US, 17% in China and 15% in Europe).

There are several reasons for this:

- Regulation – US laws and regulations are less strict for AI companies.

- Tariffs – land is cheap and energy costs are low in states where centres are usually built.

- Human capital – most of the world’s top engineers, programmers, researchers and students are based in the US.

- Security – with intense global competition, physical and cyber protection of data, infrastructure and processes is a priority.

Still, building data centres abroad also brings major advantages.

Geographic distribution reduces the time needed for end users to access services. Many countries also require confidential data to remain on their territory, reinforcing data sovereignty. And the construction of costly infrastructure signals a company’s long-term interest in the country — or even the entire region — while helping to build trust with local governments and businesses.

Data centres are already considered critical infrastructure, demanding a high level of security. In the age of AI, they are set to play the role that oil and gas pipelines once did in regional security.

Armenia with practical progress, Azerbaijan with strategic vision

On 29 August, the US State Department published the texts of the signed memoranda.

They show that cooperation with Azerbaijan is planned on a strategic level, including the creation of a working group to draft a US-Azerbaijan Strategic Partnership Charter.

Three main areas of the charter have already been defined, one of which is “economic investment, including artificial intelligence and digital infrastructure.” More specific details are expected in about six months.

The memorandum signed with Armenia, titled On Innovation Partnership in Artificial Intelligence and Semiconductors, is highly specific and carries a very different weight.

It goes beyond cooperation in technology alone. Alongside establishing full-scale collaboration between Armenia and the US in AI and semiconductors, the memorandum also provides for steps to introduce export control mechanisms.

The US will take the lead, while Armenia will support the creation and implementation of reliable semiconductor export systems to ensure the security of AI, its products and supply chains.

The context and significance of the memorandum becomes clearer when recalling the June announcement that US tech giant NVIDIA — the world’s largest company by market capitalisation — and cloud company Firebird are implementing a $500 million project in Armenia.

As part of the project, Armenia will host a regional AI supercomputing centre with a capacity of 100 megawatts, aimed at fostering innovation, AI research, education and economic development in the region.

The semiconductors (graphic processors) to be used in the NVIDIA centre are not only cutting-edge technology but also dual-use, with both military and commercial applications. This helps explain why the memorandum places strong emphasis on export controls.

The AI centre in Armenia is expected to open in 2026 and will be the largest technology investment project in the South Caucasus. The Armenian government has already guaranteed uninterrupted electricity supplies for investors and is considering various tax incentives.

China, meanwhile, was slightly late in signing its own strategic partnership agreement with Armenia. That document was finalised on 31 August during prime minister Nikol Pashinyan’s visit to China. It also provides for cooperation in AI, technology parks and joint research centres, but is more of a declaration than the detailed memorandum signed with the US.

And what about Georgia?

Against this backdrop, Georgia looks increasingly uncompetitive.

In 2009, Georgia signed a Strategic Partnership Charter with the US, but in 2024 Washington suspended its implementation in response to the anti-Western policies of the ruling Georgian Dream party.

Georgia’s EU accession process, as well as cooperation frameworks with the UK and other Western democracies, have also been frozen or scaled back — again due to Georgian Dream’s retreat from democratic principles.

The crisis of democracy in Georgia creates geopolitical and economic risks for major Western companies and undermines the country’s attractiveness.

Developing and developed states that lack the resources to build their own AI systems are competing to offer tech giants favourable conditions: tax breaks, lighter regulation, cheap energy and access to infrastructure.

But for political reasons, the Georgian government can now only offer such a package to its sole remaining strategic partner — China.

Beijing has spent nearly a decade advancing its Digital Silk Road alongside the Belt and Road Initiative, with Georgia positioned as a key link in the “Middle Corridor.” Chinese officials have repeatedly said they want Georgia included in their AI ecosystem.

Leaders of Georgian Dream have already held frequent meetings with Chinese party officials and telecom executives, especially with Huawei, which is building 5G networks and data centres along the Digital Silk Road.

Yet in 2021 Georgia signed a memorandum of understanding with the US that ruled out cooperation with Chinese companies in developing 5G networks.

Washington and almost all developed democracies had already banned Huawei, citing serious security concerns over its networks, equipment and data protection.

Even so, Huawei says it has built up to 75% of Georgia’s networks. In 2024, former economy minister Levan Davitashvili argued that Huawei’s expertise in optimising data centres and AI infrastructure “perfectly matches Georgia’s vision of becoming a regional hub for digital transformation.”

Just a few months ago, current economy minister Mariam Kvrivishvili presented Huawei’s regional president with the Kutaisi Tech Hub project, offering cooperation on an AI lab, data centre, international IT faculty, start-up accelerators and other initiatives.

Rising regional competition — especially the surge in expected foreign investment in Armenia and Azerbaijan — is likely to push Georgia’s government into taking even bolder steps toward cooperation with China and launching concrete projects.

That will not require much additional effort from Tbilisi, since almost all major infrastructure and energy contracts in recent years have already gone to Chinese companies.

As a result, AI will become yet another sphere in which Georgia does not align with the West. The rhetorical question “Where are we?” will no longer make sense: Georgia will have taken its place on the other side of the geopolitical divide.

AI in Armenia Azerbaijan and Georgia