"Vicious cycle: when political rivals are financial groups" – interview with Abkhazian presidential candidate Oleg Bartsyts

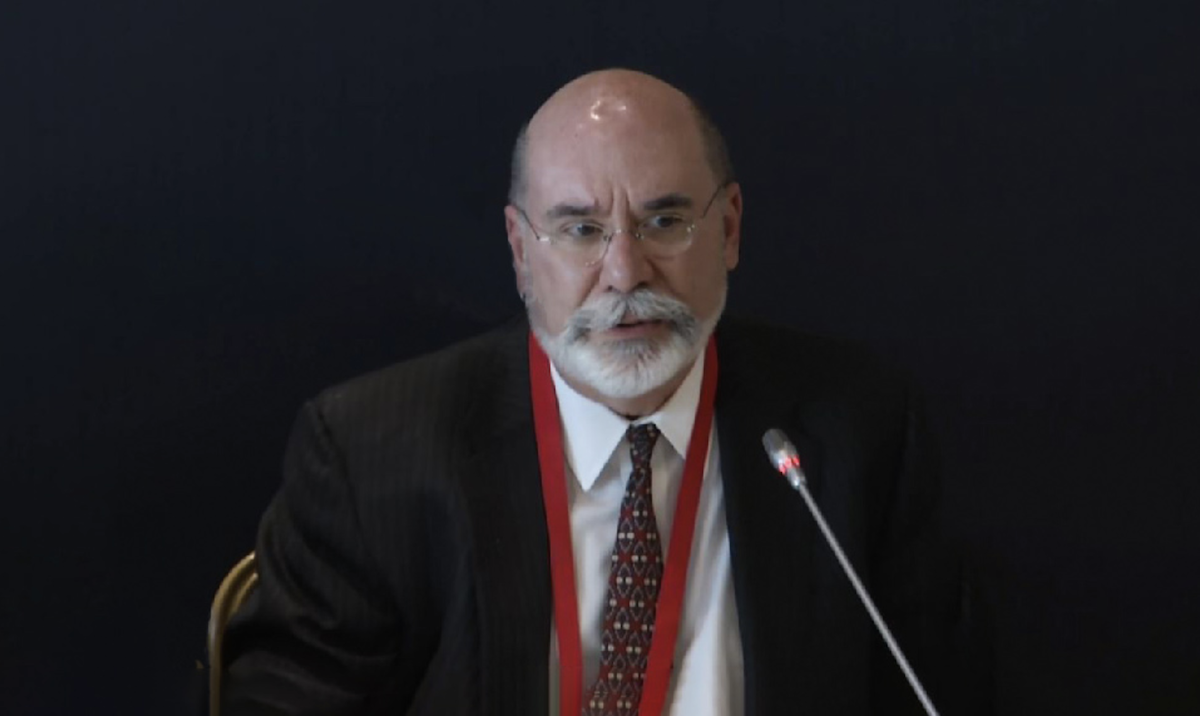

JAMnews editor in Abkhazia and “Chegemskaya Pravda” editor Inal Khashig interviewed Abkhazian presidential candidate Oleg Bartsyts. The early election is set for February 15.

Topics discussed:

- Why he decided to run for president

- The power-money-influence cycle in Abkhazia, two rival financial groups, and ways to break this vicious cycle

- His relationship with former Prime Minister Alexander Ankvab and why they are now on different teams

- Insights on the country’s talent pool based on his experience in four presidential administrations

- How Abkhazia can overcome the energy crisis

- Relations with Russia: causes of the crisis and the possibility of a reset

- The need to strengthen military cooperation with Russia to enhance Abkhazia’s security.

- Proposing that Russia establish a full-scale naval base in Abkhazia to control the eastern Black Sea region, including Georgian ports Poti and Batumi.

Full text of interview:

Inal Khashig: Hello, and welcome to Chegemskaya Pravda. The presidential elections are in full swing, and, of course, we are going to talk about them. Today we have one of the five candidates in this election — Oleg Bartsits. Oleg, good evening.

I won’t be theatrical or play any roles. We’ve known each other for 40 years, we studied together and are friends. But that doesn’t mean we share the same views on everything. Sometimes we see things differently, though often our opinions align. Nevertheless, today we will be speaking publicly.

My introduction turned out to be quite long, but let me start with this question: why did you decide to run in this election? The situation is complicated right now. There are serious problems facing Abkhazian society; over the years two political camps have emerged, alternating on the political field but deepening the crisis without resolving it.

I see your meetings with voters, and I see how forces are concentrated in these camps. Why have you decided to run now, not aligning with either of them?

Oleg Bartsits: Good evening. Your question already contains part of the answer. Abkhazia is currently in the midst of an election campaign. Once again, we see fierce political competition between two main camps: the pro-government and the opposition.

This cycle repeats itself election after election. Harsh rhetoric, tension, conflicts — nothing new. You asked why “suddenly.” But I don’t consider my decision unexpected.

Back in 2009, I participated in the presidential elections as a vice-presidential candidate alongside my friend and ally Oleg Arshba. He remains an important member of our team today, occupying a key position among staff and like-minded individuals.

So, I cannot consider myself new to politics. Moreover, I know the Abkhazian political and governmental system firsthand. I have been part of this sphere for decades.

As for the reasons for my candidacy, they are tied to the fact that, over the past twenty years, two camps have dominated the political arena. They replace each other, but ultimately they are not much different. Political life has come to resemble a confrontation of “portraits”: one camp is associated with certain faces, the other with others.

There are no fundamental differences between them. In times of crisis, harsh rhetoric flares up, directed at opponents, but it does not change the essence.

The trigger for the current crisis were initiatives proposed by Aslan Bzhaniya’s team. These innovations have caused heated debates within society and the political elite. I considered these initiatives unacceptable at this stage and said so.

I explained calmly, without hysteria, presenting arguments that are quite evident. Prolonged political confrontation has bred apathy and disbelief among citizens in the possibility of change. On the other hand, our society still retains its passion and readiness to act in pivotal moments.

Inal Khashig: Society does indeed retain its energy, but the division is obvious. In your opinion, how can this vicious cycle be broken? During every presidential election, candidates talk about the need to unite society, but as soon as the elections end, unification doesn’t happen.

On the contrary, the division deepens. By the second or third year, people start avoiding each other. Is there a way to change this system and overcome the sentiments that have developed over the years?

Oleg Bartsits: Well, look. We know how our political reality is structured. When a new political team comes to power, especially during periods associated with early power transitions — which have happened three times in Abkhazia — we face the same problems.

These acute phases, accompanied by manifestations of what we might call our “street democracy,” inevitably result the need to return to a legitimate framework.

Our society, fortunately, always demonstrates common sense and caution, returning processes to a legal framework through elections. But after elections, everything repeats itself: the winner finds himself surrounded by his supporters, who, during the acute phase of the conflict, “wrote blank checks.”

These people demand recompense in the form of ministerial positions, administration posts, various contracts, or loans. Team formation is based not on knowledge, competence, or experience but on personal loyalty or affiliation with a particular political group.

Everyone talks about the need to unite society, but in practice, this is mere lip service. That is why my associates and I decided to take a practical step. We are convinced that unity is impossible without selecting managers who genuinely deserve their positions.

Although we do not have the largest bench, there are competent and experienced people with solid knowledge, but many of them have been excluded from the process.

We concluded that political affiliation and past actions are irrelevant.

For example, I am associated with the teams of Sergei Bagapsh and Alexander Ankvab, although I worked in Raul Khajimba’s government for six years. I am not ashamed of that period, and I consider it worthy.

Adgur Kakoba belonged to another team; he was the Minister of Education in Khajimba’s government. We don’t care who voted for whom or which candidate someone supported.

The only things that matter are competence, responsibility, and willingness to work for the benefit of the country while leaving personal interests aside.

We understand this is a challenging task, but it is necessary. Personal examples are not enough; it’s essential to set the right direction. Unity will not happen overnight, but at least we will start moving in that direction.

If we establish the correct trajectory, those who come after us can traverse this path. For a small country like ours, with limited resources and population, this is a matter of survival. In the modern world, full of challenges and threats, national unity becomes the key to development.

Inal Khashig: This is an important topic and we will return to it. But for now, I want to continue the thread on domestic politics. In the previous elections, you ran alongside Oleg Arshba, with Alexander Ankvab heading your campaign headquarters. Society still discusses this, claiming you are his protégé.

However, Ankvab now supports another candidate. I understand the situation, but I would like you to explain it yourself.

Additionally, you were one of the few high-ranking officials who openly expressed their position on apartments and investment agreements, which did not align with the views of Aslan Bzhaniya’s and Alexander Ankvab’s teams.

Could you provide some clarity?

Oleg Bartsits: I think this needs to be divided into two questions. Regarding Alexander Ankvab, it is well known that he now supports another candidate and heads their national campaign headquarters. Yes, it is widely known that Alexander Ankvab actively supports one of the candidates. And it’s certainly not me.

My team and I decided to go our own way, with all the consequences this entails. Alexander Ankvab has every moral and legal right to support whomever he deems appropriate.

As for the discussions going on, I don’t know what goals they serve. But within our team, everything is clear: no one stands behind us, no one is forcing us to run, and no one initiated it. On the contrary, we pursued this despite various opinions.

At the same time, we have never hidden the fact that if any experienced politician or manager, long present in Abkhazia’s political arena, wants to support us, we would welcome it. But the reality is that each of them — Alexander Ankvab and Raul Khajimba — has their candidates, and it’s not us.

I don’t see the point in emphasizing this, but I understand why this topic is being discussed. We chose our path, and personally, I find great satisfaction in the fact that we are moving along independently. We can win or lose, but that’s not the end of life. We are doing what we consider right, fair, and beneficial in the long run.

There are no second or third motives behind this, although some find it convenient to portray it differently.

Inal Khashig: You’ve mentioned that you worked under practically everyone: Sergei Bagapsh, Alexander Ankvab, Raul Khajimba. You also talked about the specificities of Abkhazia’s bureaucracy, where professionalism, knowledge, and experience should be the main criteria. Given the size of our nation, it seems difficult to form a complete team from representatives of one group.

Looking at your team, I don’t see a complete team. Everyone faces a similar situation: finding truly competent people is challenging. Could you name those you consider professional managers, with whom you’ve worked or seen in action?

Oleg Bartsits: There’s no secret here. In our political rhetoric, there is often a myth that one camp is entirely talented, honest, and selfless, while the other is exclusively incompetent and corrupt. We all know this is not true. Both camps have about the same share of good and bad individuals.

In my 19 years of government service, I’ve seen various political teams. And under each president, there were people who impressed me with their work. This doesn’t depend on their political orientation.

If we talk about specific names, for example, Daura Leontievich Karmazina — great potential, unfortunately underestimated in our management system. His work as Minister of Taxes yielded respectable results. Beslan Barateliya, in the field of economics, I highly value the professionalism of Anna Valeryevna Adleiba.

In international politics — Vyacheslav Andreevich Chirikba and Irakli Khintba. Among young managers, I would highlight Kan Tania — a talented and mature specialist.

Regarding the Ministry of Emergency Situations, Lev Konstantinovich Kvitsinia is a man who is undoubtedly in the right place. In the parliament, there are also talented and responsible people. For example, Speaker Lasha Ashuba and Deputy Inar Gitsba.

Our parliament often becomes a crisis-management institution during acute political moments.

Among regional leaders and vice-mayors, there are also individuals who stand out for their systemic approach. For instance, Astamur Ashuba is one who creates an atmosphere of efficiency around him.

I firmly believe that if we stop dividing professionals into political factions and adopt an objective approach to staffing, we could assemble a highly capable government. Among diplomats, Igor Muratovich Akhba deserves special mention; he is one of the pillars of our diplomacy, consistently demonstrating the highest level of professionalism.

Likewise among our business community there are strong leaders. For example, Astamur Gennadyevich Gaguliya is a successful manager whose work commands respect.

Abkhazia does not lack qualified personnel. The key is to stop fragmenting professionals based on political alignments and to channel their talents toward the benefit of the country.

Inal Khashig: One of the toughest issues is clearly the energy problem. Even now we have to time our broadcasts around power outage schedules. In winter, this issue becomes especially urgent, but once the season ends, as usual, we’ll forget about it until next winter.

Energy has become not only an internal issue but also a factor in foreign policy. How do you think this problem can be solved?

Oleg Bartsits: The energy situation is indeed almost at a deadlock. To be honest, our energy system is in a state of systemic crisis. The deterioration of our infrastructure, transmission systems, and equipment makes it impossible to use even the power generation capacity we currently have.

Our only major power-generating facility is the Inguri Hydroelectric Power Plant. A significant portion of that electricity is lost during transmission due to the poor condition of the grid.

These problems have built up over the years, and virtually no real steps have been taken to restore the infrastructure. Another issue is payment collection. This is because people are understandably frustrated by the imbalance: while rates go up, service quality remains low. When someone gets 120 volts instead of 220 at home, and their appliances fail because of it, they naturally ask: why should I pay for this?

These circumstances create a trust problem, which is further aggravated by corruption. We are doing very little to develop new power-generating facilities. Before the war in Abkhazia, there were 22 small hydroelectric plants in operation; today there are only four.

If restoring such plants were a priority, things would look very different. For example, I’ve seen a cascade of four small plants in Chechnya that solve a multitude of problems. With our hydro potential, we could pursue similar projects. Abkhazia ranks fourth in hydro resources relative to its land area.

In addition to small hydropower plants, we must develop alternative energy sources. Wind farms, for example, are widely used in many countries, and we have suitable locations for this. Specialists have already measured wind speeds in our valleys and confirmed their feasibility.

But these initiatives often face opposition. I believe this is because many leaders treat their sectors as personal fiefdoms and are not interested in change.

There are other suggestions, such as selling the energy grid to investors. I’m not against investments, but they must be mutually beneficial. Energy infrastructure is a cornerstone of our sovereignty. We need to select proposals that are advantageous both to the country and the investor.

A major step forward would be a state energy conservation program. This will require effort, but many countries have already embraced this path. If service quality improved and people saw tangible changes, they would be more willing to pay for electricity.

It’s also essential to implement monitoring and control systems. For instance, in homes with electricity meters, payment collection reaches 95%, and losses are reduced by 30%.

Today we have enough professionals in the energy sector who can propose solutions. We need to give these people the opportunity to work and engage them in dialogue. The expert community should be part of the decision-making process. I often consult with such specialists, and they consistently offer practical, well-considered solutions.

Inal Khashig: Energy is clearly a problem that cannot be resolved overnight. But there’s another difficult topic — our relationship with Russia. With the political crises that have arisen since November 15 and the broader geopolitical challenges, how should we build these relations after the presidential elections?

Oleg Bartsits: First of all, we need to be honest about why certain problems arise in relations between Russia and Abkhazia. The main reason, in my opinion, is the behind-the-scenes and hasty nature of decision-making, without involving society, parliament, or experts. Such an approach inevitably leads to crises.

Russia is our main strategic ally. It is the only country that minimizes our military and political risks while supporting socio-economic development. However, this relationship requires honesty, pragmatism, and predictability.

If we prepared our agenda in advance and gradually aligned our positions with Russian partners, we could avoid sharp crises like the one in November. Russian officials I recently met said: “Be honest with us. If you can’t agree to something, just say so immediately so we can explore alternative options.”

We must openly and pragmatically discuss our priorities and concerns. This will make cooperation more dynamic and mutually beneficial. No one will take care of us more than we ourselves. That’s why it’s essential to conduct an honest and professional dialogue with Russia.

Abkhazia and Russia are connected not just by treaties of alliance and partnership but also by deep human, cultural, and humanitarian ties.

I firmly believe that Abkhazia’s development is possible only in partnership with Russia. We have no other prospects.

Inal Khashig: I completely agree.

Oleg Bartsits: In the public consciousness of both Russians and Abkhazians, nothing has changed. We still view each other as partners and friends, and this will continue. The mistakes of officials need to be corrected — it’s that simple. That’s the direction we should be heading in.

When it comes to security, this is an extremely important issue. In today’s conditions its significance is growing rapidly, especially given the events in the South Caucasus. We are witnessing major shifts that were hard to imagine just a short time ago.

Who could have predicted that Yerevan and Washington would sign a strategic partnership agreement? This opens the door for the U.S. to establish a presence in Armenia, potentially replacing Russian bases with American. In Georgia the situation remains unpredictable.

Despite statements about improving relations with Russia, Georgia’s priorities remain unchanged: reclaiming Abkhazia and South Ossetia and maintaining a Euro-Atlantic course.

The region is seeing increased activity from NATO and the US, as well as closer cooperation between Turkey and Azerbaijan. This is happening right next door to us. For instance, the construction of NATO’s largest base in Romania. Russia, facing its own challenges and threats, is closely monitoring the situation.

Abkhazia cannot remain passive, hoping these problems will resolve themselves. We need to strengthen military cooperation with Russia and enhance our own security. The regional security architecture is undergoing massive changes, and we need to be prepared.

I believe Abkhazia could propose hosting a full-fledged Black Sea Fleet naval base closer to our eastern borders. Yes, we already have a base in the Ochamchira district, but a fully developed base could significantly improve stability and security in the region.

This would benefit both Abkhazia and Russia, allowing for more effective control of the eastern Black Sea, including Georgian ports like Poti and Batumi. Such an initiative aligns entirely with Russia’s naval doctrine, adopted in 2022.

With its 218 kilometers of coastline — far more than Georgia’s — Abkhazia could play a key role in strengthening Black Sea security. Joint exercises planned between Georgia and NATO in May 2025 only underscore the relevance of such initiatives.

We must be a reliable and predictable partner for Russia. This is in the interest of our security and the stability of the region.

Inal Khashig: I think we’ll continue discussing these topics on other platforms. Today’s broadcast isn’t limitless. We’ve been talking about the future, its prospects, and current challenges with presidential candidate Oleg Bartsits. Oleg, best of luck to you.

Oleg Bartsits: Thank you.

Inal Khashig: I hope the elections go smoothly. Maybe someday Abkhazia’s political “Groundhog Day” will end, and we’ll move toward development. Bye Oleg, until next time.

Terms, place names, opinions and ideas suggested by the author of the publication are their own and do not necessarily coincide with the opinions and ideas of JAMnews or its individual employees. JAMnews reserves the right to remove comments on posts that are deemed offensive, threatening, violent or otherwise ethically unacceptable.